News & Issues July 2022

The cost of connectivity?

Cell tower dispute puts Pittsfield at center of a national debate

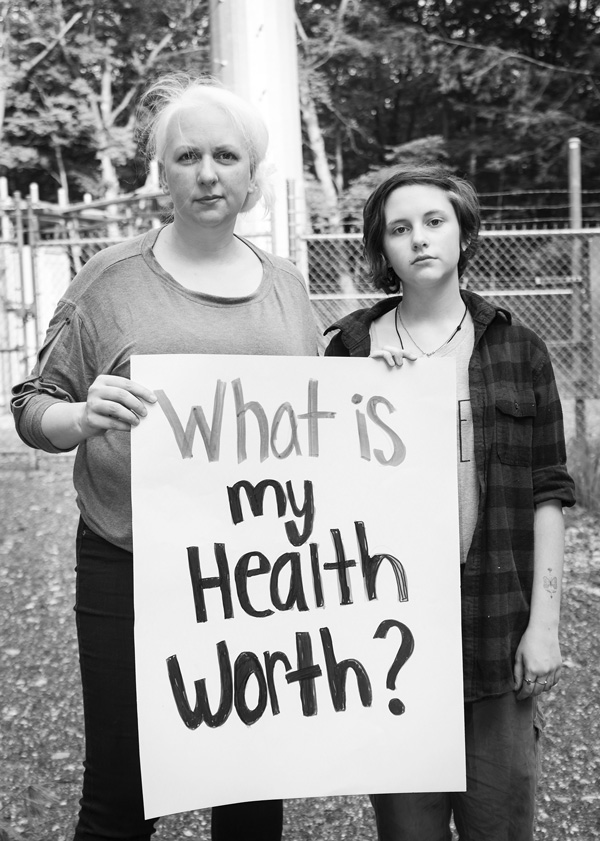

Courtney Gilardi and her daughters stand outside their home in Pittsfield, Photo by Susan Sabino.

By TRACY FRISCH

Contributing writer

PITTSFIELD, Mass.

Courtney Gilardi’s 9-year-old daughter came downstairs one morning in the late summer of 2020 and announced that she was feeling “headachy, dizzy and buzzy.”

Over the next few weeks, Gilardi said she watched with alarm as the health of both her daughters deteriorated. They struggled to sleep at night and lost their appetites and ability to concentrate. Eventually, she said, both girls “got so sick that they were sleeping with vomit buckets by their beds.”

Her daughters’ symptoms began soon after Verizon powered up a new cellular communications tower less than 500 feet from her home on a dead-end street near Holmes Road in the southern part of Pittsfield.

When Gilardi took her daughters to their pediatrician, the physician told them about an epidemiological study that showed people living near mobile phone base stations faced increased risk of developing headaches, memory problems, dizziness, depression and sleep problems.

“It was everything that we had,” she said.

Gilardi’s daughters weren’t the only ones feeling sick. Her next-door neighbor, Elaine Ireland, soon confided that she had been experiencing similar symptoms.

“My ears were ringing,” Ireland recalled. “I had a headache. I couldn’t sleep. I’ve never been a headache person.”

Gilardi, a former preschool teacher, organized and began to collect health reports from other people in the neighborhood who said they had begun feeling unwell after the cell tower was turned on. She also began waking up with heart palpitations in the middle of the night.

“People would knock on my door and tell me about a new symptom,” she said. “The tower got turned on at the end of the summer. By December, we knew of 17 people who got sick.”

Health board takes action

Gilardi and her neighbors started showing up at Pittsfield City Council meetings in the fall of 2020 and asking for help. The city had granted a zoning variance in 2017 allowing construction of the 115-foot-tall cell tower, even though the people living closest to the tower say they were never directly notified that the project was under consideration.

In early 2021, the council asked the city Board of Health to look into the health issues reported by the tower’s neighbors.

Over many months, the board gathered testimony from the neighborhood’s residents and their physicians as well as several medical and scientific experts who have studied the health effects of radio-frequency radiation. The board also met twice with a Verizon representative.

As the city’s investigation unfolded, Gilardi learned more about the growing body of scientific evidence linking radio-frequency exposure to a variety of health problems in humans and other living organisms. After news reports about the Pittsfield controversy, she heard from advocacy groups like Massachusetts for Safe Technology that offered advice and put her in touch with experts.

At the same time, some in the neighborhood were deciding they could no longer tolerate the symptoms they were experiencing. Several left the area temporarily or moved in with relatives. Two families managed to sell their homes and move out for good. Others resorted to sleeping in their cars after driving out of range of the cell tower.

By March 2021, the Gilardis began spending their nights at a rundown cottage they owned in Lenox. They’d return home in the morning for the girls’ remote schooling.

“The girls love their home and their rooms,” Gilardi said. “But by the end of the day, they would feel sick and want to leave.”

By September, after extensive repairs to the cottage, the family moved there full time.

Finally, this spring, the city Board of Health took action. In early April, the board sent Verizon a 23-page “cease and desist” order directing the company to turn off its tower or request a hearing where it could make its case for continued operation.

The board’s emergency order documented 20 cases of people living near the tower who developed health problems after the cell tower began operation, and it concluded that the tower’s radio frequency emissions had rendered nearby homes uninhabitable.

The board said it found credible evidence linking the cell tower’s radio-frequency emissions to residents’ health complaints, and its order cited more than 1,000 peer-reviewed scientific and medical studies “which consistently find that pulsed and modulated RFR [radio-frequency radiation] has bio-effects and can lead to short- and long-term adverse health effects in humans, either directly or by aggravating other existing medical conditions.”

Setting a precedent?

The Board of Health’s ruling set up a legal test case of potentially national significance, and it quickly caught the attention of public-interest advocates around the country. Many of them have long criticized the federal Telecommunications Act of 1996, which they say gave cell-phone companies carte blanche to ignore health and environmental concerns in the siting of transmission towers.

Theodora Scarato of the Wyoming-based Environmental Health Trust said she believes the Pittsfield ruling was the first time a local health authority had ordered the shutdown of a cell tower based on documented health effects.

The emergency order initially left Gilardi and her neighbors feeling elated, but the sense of triumph proved to be short-lived.

“We’ve been completely vindicated by the Board of Health’s investigation,” she said in an interview in early May.

But on May 10, Verizon went to federal court in Springfield and asked for a declaratory judgment to stop the Pittsfield Board of Health from enforcing its emergency order. In court papers, the company argued that the Telecommunications Act of 1996 prohibits the city from regulating cell towers on the basis of radio-frequency emissions – and that the board “improperly based its order on the premise that the RF emissions from the facility have health effects.”

On June 1, the board withdrew its cease-and-desist order. The order had been conditioned on the board being able to retain legal representation to defend its ruling in any court or administrative challenge. But throughout April and May, the City Council repeatedly failed to act on the board’s request for up to $84,000 to hire outside lawyers who had agreed to take the case.

Board of Health Chairwoman Bobbie Orsi said at the board’s June 1 meeting that board members wanted to help the cell tower’s neighbors but that she now believes “litigation is perhaps not the process that’s … going to help resolve the issues.” Orsi did not respond to a request for an interview for this report.

Courtney Gilardi stands with one of her daughters at the base of a cell phone tower that was built two years ago behind their home. The Gilardis and their neighbors say the tower has been making them sick. Susan Sabino photo

Disputed safety standard

In its court action, Verizon argued that state and local governments are barred under the Telecommunications Act of 1996 from regulating cell towers based on “perceived health effects” from radio-frequency emissions — as long as those emissions fall within the safety limits set by the Federal Communications Commission.

And the company has pointed out that measurements of RF radiation taken at the Pittsfield tower by third-party contractors within the past year have been well below the FCC’s safety threshold. (Verizon’s representatives did not respond to multiple requests for an interview for this report.)

But many public health and environmental advocates say the FCC safety standard, set in 1996, is long overdue for an update. And last year, a federal appeals court ruling called the legitimacy of the current standard into question.

Nearly a decade ago, in 2013, the American Academy of Pediatrics called on the FCC to update its safety standards for radio-frequency radiation to protect children’s health and well-being and to reflect the explosive growth in use of wireless devices since the 1990s.

“Children are not little adults and are disproportionately impacted by all environmental exposures, including cell phone radiation,” the pediatricians wrote in their letter to the FCC. “It is essential that any new standard for cell phones or other wireless devices be based on protecting the youngest and most vulnerable populations to ensure they are safeguarded throughout their lifetimes.”

And over the past decade, advocates say the evidence of health effects from radio-frequency emissions well below the FCC limit has continued to mount.

Scarato, of Environmental Health Trust, decried what she called a failure of government regulation.

“The scandal is not what is illegal, but what is legal,” she said.

In 2019, the FCC opted not to update its 1996 regulations for allowable exposures of radio-frequency radiation from wireless technologies, including cell towers, in light of new scientific evidence. But Environmental Health Trust led a coalition of groups that challenged the FCC’s inaction in court. The petitioners submitted more than 11,000 pages of evidence documenting biological effects and illness from wireless radiation exposure below the FCC’s safety threshold.

Last summer, the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia sided with the advocates and sent the FCC back to the drawing board to either justify its current safety standard or produce a new one. The appeals court ruled that the FCC’s decision was “arbitrary and capricious” because it failed to respond to evidence that showed exposure to radiation at levels below the commission’s current safety limits may cause negative health effects other than cancer. The court also found the FCC to be “arbitrary and capricious in its complete failure to respond to comments concerning environmental harm caused by RF radiation.”

Scarato called the FCC safety standard “irrelevant and outdated,” pointing out that it was created at a time when cell phones were rare and use of the Internet was just beginning.

“How is it OK that the standards are almost three decades old?” she asked. “We need a thorough review done by top scientific experts.”

Today, 97 percent of Americans own a cell phone, and wireless Internet devices are ubiquitous.

“There’s been no pre-market health testing for long-term effects,” Scarato said. “There’s no post-market surveillance or monitoring of the levels to which people are exposed. The FCC and EPA used to do monitoring, but EPA’s last report on its monitoring dates back to 1986, and the office was defunded.”

Many other countries, including Italy, Israel and India, have more stringent exposure limits for radio-frequency radiation from cell towers. Some also provide stronger protections for homes and schools, with prohibitions on placing towers too near parks, hospitals, elderly housing and other locations with vulnerable people. About 20 countries regularly measure radio-frequency radiation from cell towers and publish the levels online, Scarato said.

Discovering risks

At the heart of the Pittsfield homeowners’ dispute with Verizon is the question of whether radiofrequency radiation, the type of non-ionizing radiation emitted by cell towers, cell phones and other wireless devices, can affect human health.

The telecommunications industry and its paid experts contend that thermal heating, which is how a microwave oven cooks or heats food, is the only way that RF radiation could harm a person’s health. Microwave radiation is a subset of RF radiation.

There is widespread agreement that ionizing radiation, a category that includes nuclear radiation, is biologically active and can cause cancer and other harmful effects. But because non-ionizing radiation is not strong enough to alter the structure of atoms, for many years it was presumed to be safe.

Experts who’ve studied the issue in recent years, however, have come to the conclusion that certain types of non-ionizing radiation produce toxic, oxidative effects on biological processes, through a process unrelated to heat or ionization. Research has shown that this type of radiation also induces biochemical changes in living cells and their membranes. The nervous system is especially sensitive to non-ionizing radiation.

Kent Chamberlin, a professor emeritus of electrical and computer engineering at the University of New Hampshire, became a vocal critic of the FCC’s safety standards after he was tapped to serve on a state legislative commission to study wireless radiation.

He said he joined the panel in 2019 with “a conventional understanding of radiation” from his engineering background. The commission was tasked assessing health and environmental effects of evolving wireless technology and making safety recommendations for the rollout of 5G wireless networks.

“Initially I felt there wasn’t any important risk,” Chamberlin said. “But I changed my mind.”

His conversion occurred once he started examining the studies of health effects from radio-frequency radiation.

“It became obvious,” Chamberlin said. “There are thousands of peer-reviewed studies showing harm.”

Chamberlin said he discovered that the results of the various studies “are dependent on who funds the research.” Only 28 percent of industry-funded studies showed biological effects, he said, while 66 percent non-industry-funded studies did.

The New Hampshire commission on which he served issued a report in 2020 recommending that all new cell towers have a 1,644-foot setback from areas zoned residential as well as from schools, parks, nursing homes and hospitals. A bill proposed in the state House of Representatives would require that setback distance and also establish a registry for residents experiencing biological symptoms from wireless radiation.

Chamberlin, who visited the Berkshires last year to speak to the Lenox Board of Health about wireless radiation, said his conclusion from examining the peer-reviewed health studies is that the FCC standard allows absurdly high levels of exposure. Because of that, he sees no point in measuring wireless emissions to see if they fall within the FCC limit.

“It’s like putting a 500 mph speed limit on I-95,” Chamberlin said. “No one would exceed it.”

But the fact that all drivers would be in compliance would not mean their speed was safe, he added.

Go or stay?

Now that the city Board of Health has backed off from its effort to shut down the Pittsfield cell tower, Gilardi and her neighbors are continuing to speak out, but their next steps are unclear.

At a City Council meeting in June, Gilardi expressed her “profound anger and disappointment” that the Board of Health had been forced to rescind its order – “and that we were deprived of justice and the opportunity to go home.”

She blames City Solicitor Stephen Pagnotta for scaring city officials away from pursuing any legal action against Verizon. And she accused him of of having a conflict of interest by being a partner in a law firm that recently has had a cell tower company, several wireless companies and a Verizon entity as its clients in litigation.

Pagnotta did not respond to a phone message seeking his response to that claim.

Ireland, Gilardi’s longtime next-door neighbor, said she considered selling her home but has decided to stay and fight.

But she said she has been exasperated by the city’s inaction and believes she and her neighbors have been “disrespected, abandoned, ignored and given the runaround.”

Ireland said she began having tinnitus, or ringing in the ear, within a day of the tower being turned on.

“When I lay down at night, within 15 minutes, the tinnitus gets loud and noticeable,” she said. “I started having insomnia. I always have slept like a baby. I’m just wondering if it’s doing this, what else is it doing?”

She said her symptoms diminished markedly when she tried staying away from home.

“I started to spend time at my parents’ in Otis,” she said. “I had a surgery and spent 10 days at my brother’s house.”

This year she spent three months in Texas after finding work there.

Ireland stressed that she is not anti-technology. But with so much land in the Berkshires, she thinks Verizon could have put its tower a thousand feet further back.

The Gilardis have taken steps to reduce their exposure to radio-frequency radiation since they moved into their Lenox cottage full time.

“In our cottage, we have everything hard-wired,” Gilardi said. “We have ethernet cables in every room. My cell phone switches to a land line. There are no wireless devices.”

Another neighbor, Charlie Herzig, said he and his wife have no plans to leave their retirement home despite health problems they attribute to the cell tower.

“My wife never had tinnitus before,” he said. “I’d had it for a number of years, but it’s gotten much worse.”

And the couple’s sleep has become so disrupted that he said it seems as though neither of them ever really sleeps.

Herzig, an avid gardener, added that since cell tower started operating, he has noticed “a huge decrease in bees,” which has forced him to pollinate certain vegetables, like his squash, by hand. He also reported seeing fewer songbirds — and that a red-tail hawk and a grey horned owl that had lived in the area have disappeared.

Herzig suggested the current legal system gives too much power to telecommunications companies at the expense of neighborhoods like his.

“Verizon is just a big bully company,” he said. “I just hate how this whole thing works. People who moved, the kids who had to sleep with a puke bucket, … that bothers me, when people will put profits over children’s health.”

The city of Pittsfield is 44 percent open space, so there are plenty of better places for putting a cell tower than at the edge of a residential neighborhood, Gilardi said.

She and her neighbors say they identified four other locations where the tower could be placed, each at a safe distance from people’s homes.

Before the cell tower went up, Gilardi took a screenshot of a map showing that Pittsfield had full 4G coverage. Verizon has argued that it needed to strengthen the signal in some people’s homes and cars.

But Gilardi said the human costs of achieving that extra level of service are unacceptable.

“It’s not worth an extra bar if it means children are sick in their own beds,” she said. “It’s not worth the human health costs.”