News & Issues April 2024

In defense of books

Some in region push back against banning efforts in schools and libraries

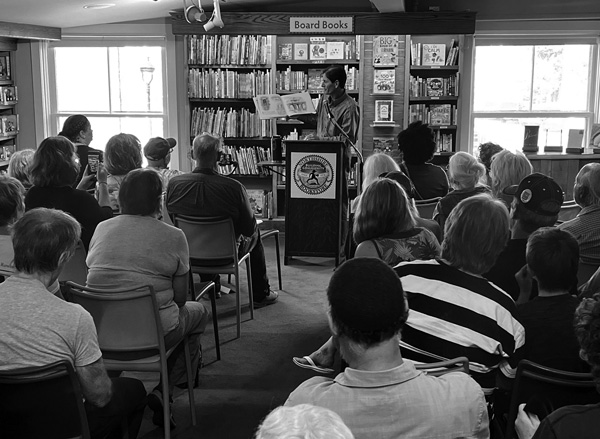

Vermont Lt. Gov. David Zuckerman reads to an audience at Northshire Bookstore in Manchester, one of a series of stops he made around the state in recent months as part of his Banned Book Tour. Courtesy photo

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

On a clear winter night, in an art studio founded by Bennington College alums, Vermont Lt. Gov. David Zuckerman was reading aloud from Toni Morrison’s “Beloved.”

Morrison was a Nobel laureate, and her novel earned the Pulitzer Prize in fiction in 1988. For Zuckerman, she tells a powerful story of the experiences of people who have lived with courage in the face of deep pain.

Sethe, a grandmother, talks with a group of enslaved people at a gathering in the woods: “In this here place, we flesh; flesh that weeps, laughs; flesh that dances on bare feet in grass. Love it. Love it hard.”

“She speaks about how these people, many born into slavery, must love themselves, because the former slave masters will not,” Zuckerman explained. “It’s a powerful scene, and one that students and everyone in America should have the ability to read.”

“Beloved” is known for its deep storytelling and understanding of the lives of emancipated, formerly enslaved people, he said.

“It is a beautiful and, at times, disturbing book that helped me, as a high school student, have a better understanding of the human impact slavery has had,” Zuckerman said. “It has also been the subject of several bans.”

Morrison has faced challenges to her books for decades, even as she has been one of the most-read writers in colleges across the nation.

Zuckerman shared her novel as he traveled around Vermont in the latter half of 2023 and early 2024 on a “Banned Book Tour,” holding community conversations in libraries and bookstores.

While he was reading aloud in Vermont, in the Berkshires the threat of banning books suddenly became more than an abstract national debate.

In December, a complaint to town police in Great Barrington resulted in an officer being dispatched to a classroom at the W.E.B. Du Bois Regional Middle School — to search for a copy of an award-winning memoir that is available at more than 100 libraries across central and western Massachusetts alone.

The Dec. 8 incident in Great Barrington set off a wave of questions and criticism in the community -- and from state and national organizations including the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts as well as from elected officials including Massachusetts Gov. Maury Healey.

A rise in bans — and resistance

The discussion of book banning — or restricting the rights of teachers to use certain books, or the rights of librarians to stock particular books — has grown more prevalent in recent years, Zuckerman said.

Around the nation, a loose network of conservative activists has tried to remove thousands of books from he shelves of schools and libraries, often in the name of “parental rights.”

Last month, the American Library Association announced that it had documented efforts to censor 4,240 unique book titles in 2023 — the largest number of book challenges ever recorded in a single year and a 65 percent increase from the 2,571 titles that were targeted in 2022. Public libraries saw a 92 percent increase in censorship requests last year, with an 11 percent increase at school libraries.

In response, movements are growing around the region to strengthen freedom of expression and the right of individuals to choose what they read and what they learn.

In Massachusetts, state Rep. Frank Moran, D-Lawrence, and state Sen. Julian Cyr, D-Truro have introduced companion bills in Legislature that would affirm schools’ and libraries’ authority to choose the books in their collections, set guidelines for book challenges and protect teachers and librarians as they do their jobs.

“Five years ago, no one would think a librarian would be under such scrutiny,” said state Rep. Tricia Farley-Bouvier, D-Pittsfield, a petitioner for Moran’s bill in the House.

As a former teacher, Farley-Bouvier said she empathizes with the pressures the Covid-19 pandemic brought to bear on parents, who have become responsible for more of their children’s day-to-day education since schools closed and went virtual during the pandemic -- and on teachers who have had to adapt to a rapidly changing environment.

But teachers and librarians are trained professionals who have the experience, knowledge and responsibility to choose the books on their shelves, she said, and conversations about the selection of books and materials should happen within schools and libraries and their boards.

National debate, local voices

In Vermont, Zuckerman’s Banned Book Tour has spurred community conversations about freedom of thought in town centers around the state. The idea for the tour came to mind a year ago, he said, as he saw news reports of book challenges in many states.

“It was becoming a major topic of conversation, not just in some of these Southern states but … all across the country,” he said.

“What’s even more disturbing to me,” Zuckerman wrote in an op-ed this winter, “is that this national trend seems to be the result of a relatively small group of people, with an agenda, who do not represent the opinion of the majority of Americans or Vermonters.

“In the 2021-22 school year, just 11 adults were responsible for approximately 60 percent of all challenges nationwide. Meanwhile, a large majority of voters oppose efforts to have books removed from their public schools and libraries.”

Now, in a presidential election year, he sees the conversation deepening as debates grow around artificial intelligence, deep fakes and false information.

“In the context of our current free speech conversations,” he said over Zoom from his office in Montpelier, “manipulated information conversations are seen regularly in the media, around elections and election fraud or even facts and stories about immigration.

“The range of disinformation is getting so great that I thought a civic conversation at the community level focused on this issue around critical thinking, education and books could be a very important topic.”

Berkshire book challenge

In Great Barrington, the topic has come close to home. According to a report released in February from an independent investigation commissioned by the Berkshire Hills Regional School District, a night custodian at the Du Bois middle school complained to town police about a book he had seen in a school classroom.

“The person who made the complaint here never talked with the school,” Farley-Bouvier said. “The book in question is at libraries across the state. If the professionals had sent the complaint to the right person, it could have ended there.”

The book was Maia Kobabe’s award-winning memoir “Gender Queer,” which explores the writer’s own sense of mind and body and experiences in coming of age.

According to the regional library consortium CW MARS, more than 100 libraries in central and western Massachusetts have copies of the book, many shelved in the young adults section. The book is readily available at local bookstores and online. It also has been a top target of book-banning groups around the country.

According to the school district’s report, the teacher whose classroom was the subject of the police search served as an adviser to the student-run Gender-Sexuality Alliance at the school. The teacher kept “Gender Queer” with other books related to the group’s interests and experiences, and students could request to borrow them.

The report does not name the teacher, and local news organizations have honored the teacher’s request not to be identified because of safety concerns.

Because the teacher has taken temporary paid leave, the school has paused meetings of its LGBTQ affinity groups, and Berkshire nonprofits have stepped in to offer support for students. The Great Barrington nonprofit Multicultural BRIDGE has been working with the schools since December, said its founder and chief executive Gwendolyn Van Sant, as have Railroad Street Youth Project and Berkshire Pride.

Within days of the police search at the middle school, more than 100 students held a walkout in solidarity with the teacher and in protest against the school’s initial response.

Parents in the Berkshire Hills Regional School District have formed a new group, Berkshires Against Book Banning, and have spoken out at school board and selectboard meetings in support of the teacher and students.

“This issue isn’t about a specific book,” the group writes in an open letter to Superintendent Peter Dillon, Principal Miles Wheat and the school community. “It is about how the district treats attempts to ban books. Banning books makes our kids less safe.”

Police response draws protest

The decision of town police to dispatch a plain-clothes investigator to the school, and the school officials’ decision to allow the officer to search a classroom for a book, both have drawn criticism locally and statewide.

“What occurred was unwarranted and unauthorized by law,” the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts and GLBTQ Legal Advocates & Defenders wrote to the town. “Contrary to your defenses of what occurred, under the laws of the Commonwealth, no criminal investigation was warranted. Your officers should have advised the complainant to raise their concerns with the school.”

After looking into the issue more thoroughly in the days after the search, Berkshire District Attorney Timothy Shugrue agreed that it would have been appropriate for any questions about the book to be handled by school officials, rather than law enforcement, and Great Barrington Police Chief Paul Storti offered a public apology for his department’s handling of the complaint.

But the ACLU expressed concern for the chilling effect these actions had on students and teachers — and not only in Great Barrington.

On Jan. 31, the Great Barrington Selectboard voted to hire an independent investigator to review the police department’s response. The results of that inquiry were not yet available as of late March.

The new legislation Farley-Bouvier supports would reaffirm that a book challenge needs to move through the school and school board or library and library board, rather than through law enforcement agents.

“I do believe in age-appropriate books and materials and curricula, inside and outside the classroom,” she added. “Age-appropriateness is important. But it shouldn’t be mixed with a discussion about censorship.”

The power of storytelling

Graphic novels like Kobabe’s, with a story or memoir told with images, can be incredibly powerful for changing people’s perspectives, said JV Hampton-VanSant, the information technology director for Multicultural BRIDGE.

These books, she explained, help readers to understand people’s lived experiences that are different from their own.

“When I was in middle school, and I was reading books from the same exact library,” she said, “I read ‘Maus’ and ‘Persepolis’ as graphic novels without any kind of warning or context. I just read them. They have some strong imagery.”

“Maus,” Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, follows his father’s experiences in the Holocaust. “Persepolis,” Marjane Satrapi’s memoir, tells stories of her childhood in Iran during the Islamic Revolution.

Both moved her strongly, Van Sant said.

“And we were watching coverage of the Twin Towers falling too, in school,” she rccalled. “Kids can handle a lot of things, … and I credit those graphic novels as the first time I understood that I’m an illustrator.”

Hampton-VanSant is a teacher of youth leaders and president of Berkshire Stonewall Community Coalition. Through BRIDGE’s community and educational programming, she has worked with children for many years as a mentor and leader of summer programs.

She said she has had young people thank her for being a role model and a presence in their lives as a Black trans woman. And as a student, she said, she would have valued “Gender Queer” and having the space to read it.

“Knowing the kids have a teacher who is a safe person, who has gone out of their way to make sure a book like this is there, that’s amazing,” she said. “And that’s a teacher I want to support — a teacher doing a lot of work outside the resources the school can provide, a teacher the kids love and want to have return.”

“As a person who would have benefitted from reading that exact book at that exact time,” she added, “it would have saved me so much time and heartache.”

Hampton-VanSant expressed concern that the police search and the events that followed have harmed students, the teacher and the wider community.

People who are strongly in favor of book banning can often come from a desire to control ideas, Van Sant said, adding that she finds this movement especially concerning when its message is, “We just don’t want these people to exist or history to reflect that their past has existed.”

Spaces for learning, exploring

One key issue when someone challenges a school or library’s choice of books is to re-hone conversations in a place where people can listen without fear or angers, said Alex Reczkowski, director of the Berkshire Athenaeum in Pittsfield.

At the Pittsfield library, Reczkowski said, patrons can always ask about a book and have a conversation with someone on the staff. They can make a request for a formal reconsideration of a book on the shelf, which would go to the library’s director and trustees. But conversation, he said, is key — having the space and time to listen to concerns and talk about why the library has chosen a book.

“Not every book is right for every reader,” he said. “But every book can have its reader. … A library’s collection should reflect the community, and our community is changing. We have more native Spanish speakers, and so we have a growing Spanish collection.”

Librarians have a sense of what people in the community are looking for, he said, from conversations at the front desk and the requests and the holds people place.

Both he and Zuckerman said they found it strange that adults would express alarm about a book in an era when so many children and teenagers have smart phones, tablets and the Internet in their hands. A child online, they said, will have broad access to information and stories in many media, often without a librarian, teacher or other knowledgeable adult to moderate or help them understand the context or meaning of what they’re reading or watching.

Dawn Jardine, who became the new director of the Great Barrington Libraries in January, said she sees libraries as a space for open exploration and creativity -- a place where people can see themselves reflected as they look out into a wider world.

Respecting parents’ rights

Zuckerman said it’s important to respect the rights of parents who want to set limits on children’s reading material or their own standard for what they believe is age-appropriate.

“People have a right to their feelings, and they don’t have to have their kid read a book,” he said. “At least in Vermont, until you’re 16, a parent can say to a teacher or librarian, ‘I don’t want my child to have that book.’ But it’s about whether you have a right to drive other children out of access to a book. And who makes that decision?”

Talking about these questions as he has toured Vermont has led to frank exchanges that he found fascinating and hopeful, Zuckerman added.

“When I speak at these events and answer questions, I actually prefer when there’s a diversity of opinions in the audience,” he said, “because then we can actually have an in-depth conversation about the different perspectives.”

He remembered talking with a grandmother and her grandson, who was about 10. Coming from a religious background, the boy expressed a frustration: He heard his school often talking about pride, and from the Bible, he understood pride as being a sin.

Zuckerman said he responded that many words have more than one definition. In the Bible, he said, pride is boastful, carrying yourself through life as though everyone else is beneath you, while the pride taught in schools means you can be confident in who you are and whom you love.

Costs of censorship

Zuckerman and Reczkowski said they have seen the movement to ban and restrict books rising in the past 5 to 10 years — at the same time as a much wider diversity of writers and stories are becoming available.

“A significant portion are books written by authors of color or nonbinary authors,” Zuckerman said. “As we’ve seen a proliferation of a more diverse set of authors, we’ve seen book-banning go up.

“We’ve also seen the book-banning efforts particularly target books that deal with race and conflict and history. Generally, these books are fully factual, and they’re just giving the facts of history.”

Through his events, he has seen banned books about many topics he feels are important to anyone — including coming of age and puberty, intimacy and safe intimacy.

“It’s shocking to me,” he said, “that we wouldn’t want to have conversations around how our bodies change, how we become attracted to people — and the discussion of consent with respect to intimacy, which is a critically, critically important factor. We know all too much that there’s way too much domestic violence in our society. … And so the conversation of consent is incredibly important.”

The state and the country have also seen many challenges to books in the queer space of writings, he said, adding that the costs are clear: For younger nonbinary or queer, gay, lesbian or transgendered youth, when they never see or read experiences like their own lived experiences, rates of depression and self-harm go up.

“So from a community health perspective, it’s critical that these books not be banned,” he concluded.

Libraries under pressure

A challenge to a book does not have to succeed, Zuckerman said, to cause harm. He explained that he’s had many conversations with librarians who are facing pressure and antagonism. Even without an active challenge, a librarian may begin asking, “Do I bring this book into our school or not? Do I display this book on our library shelves or in a topic display that might be in the library?”

They are asking these questions not because they have any doubt about a book’s value but just to avoid hostility.

Around the Northeast, libraries have come under pressure, and for some the consequences have been severe. At the southern edge of the Adirondacks, the Rockwell Falls Public Library in Lake Luzerne, N.Y., reopened in March after being shuttered for nearly six months in the aftermath of a public outcry sparked by a planned drag story hour. Contention at the library’s board meetings had escalated to the point of physical conflict, and two of the library’s three staff members and all but two of its board members resigned.

The Berkshires, in contrast, have seen support for libraries and their programming. On March 5, more than 30 people demonstrated outside the public library in Lee in support of a drag story hour after reports that opponents might protest the event.