News & Issues June 2023

Reimagining a river

Flood-control update offers chance to revive North Adams’ links to the Hoosic

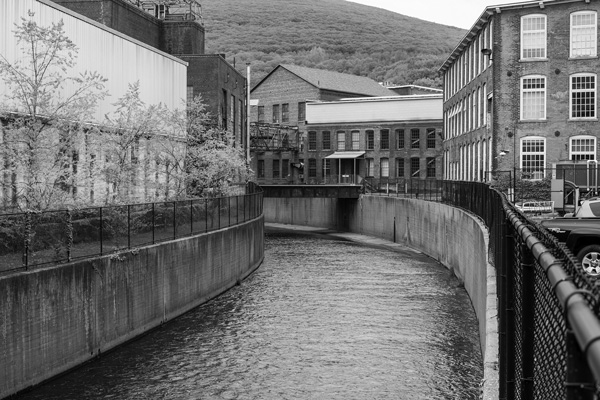

Seen from the Brown Street bridge, the north and south branches of the Hoosic River converge just west of downtown North Adams, each contained within massive concrete chutes built in the 1950s. Joan K. Lentini photo.

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

NORTH ADAMS, Mass.

On hot days, people are tubing in midstream, fishing and wading in the shallows. Where the Hoosic River runs through Williamstown, the water takes some finding, but the locals know it. In summer they may be riding along the new bike path or sitting on a natural pocket of sand where the river bends.

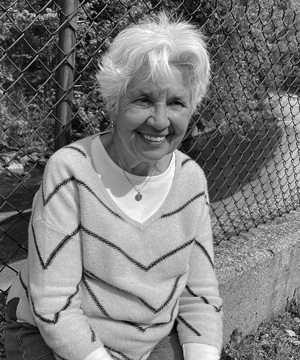

But head two miles upstream and the landscape shifts dramatically. In North Adams, many people don’t know the city has a river at all, says Judy Grinnell, the president and founder of Hoosic River Revival.

Judy Grinnell

Grinnell is standing in a paved lot on Willow Dell, just past Eagle Street, looking at a concrete wall that’s about 15 feet tall. And part of the wall is falling in.

For more than three miles in Adams and North Adams, the river runs through concrete flood chutes that are 60 to 70 years old.

The Hoosic faces a range of challenges to a healthy flow of water for the plants and animals and people who live along it. Local nonprofits and volunteers have talked for decades about the river’s future. And now that discussion is taking a new turn.

In February, North Adams secured federal, state and city funding for a feasibility study by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Between 1950 and 1961, the corps built the chutes that guide the Hoosic through the city as part of a larger flood mitigation system that stretches from Adams to the Williamstown line.

Now, 70 years on, the agency is coming back to re-evaluate and offer redesign options for the river’s flood-control system — in conversation with naturalists, ecologists, environmental scientists and the people who come to the water to cool off, look for trout, or pick up trash along the riverbank.

Local groups hope the conversation will lead to changes that bring new life to the river, restore its ecology and grow its resilience to the effects of climate change. They want to continue to protect against flooding, but many also want to find ways to reconnect North Adams to the river — creating more public access for recreation and more benefits to the downtown and the city’s economy.

The study will hold a kickoff community celebration on June 16, with a series of listening sessions to begin this summer, Grinnell said. The Army Corps of Engineers has created a team to begin the study, she said, and the Berkshires also will have a team — three people from Hoosic River Revival, the mayor of North Adams and a member of City Council, and a professional who will be hired as a manager.

Grinnell said she wants to hear people’s concerns and dreams: “Do you want a bike path, a place for picnics, a river you might sit beside?”

She looked across the way and around her at the houses in the neighborhood.

“It’s their river,” she said. “It belongs to the people who live here.”

Seeking a range of voices

Hoosic River Revival, a nonprofit formed in 2008 with the specific mission of reconnecting downtown North Adams to the river, will play a role in guiding the study process, Grinnell said. But many other local groups and interests will be involved.

The Hoosic River Watershed Association, known by the acronym HooRWA, has looked after the ecological health of the river for nearly four decades and works to protect it across three states — from the headwaters in Cheshire through the northwest corner of the state, into Vermont and across the Taconics into New York, where it enters into the watershed of the Hudson River.

The association’s executive director, Arianna Collins, and other leaders say redesigning the flood-control system in North Adams could yield major ecological benefits for the Hoosic. And making the river more accessible for recreation and enjoyment would give more people a stake in it, she suggested.

“If people don’t know and love the river, they won’t try to protect it,” Collins said.

The study process also will draw participation from a range of local groups and activists and those with interests ranging from recreation to downtown revitalization.

“We can make the river inclusive,” said North Adams native Geeg Wiles. “Everyone can be involved.”

Growing up in North Adams, Wiles said he would head east over the ridge to the Deerfield River to raft or kayak or swim, because he couldn’t get close to the water in his own hometown.

“Why can’t we play in the river?” he said. “I hope the community can come together and show them what we want the community and the river to look like in the next 100 years.”

He sees the three-year feasibility study as a time to catch the Army Corps of Engineers’ attention and offer ideas. Wiles is a marine biologist and has been a rafting guide on the Deerfield River for more than 10 years.

He’s also a community organizer: As founder of Ahab’s Adventures, he said, he has worked with many other communities to improve their rivers’ health and access. In June, he’ll be visiting reimagined rivers in Boise, Idaho, and Boulder, Colo., that acted more than a decade ago to implement the kinds of designs he’d like to see in North Adams.

Dealing with old dams

In the quest to make the Hoosic more accessible, Wiles is focusing on six lowhead dams east and west of downtown. They too are aging, he said, like the flood chutes, and where the river does flow in North Adams, the dams make the water dangerous for swimming or boating.

People call the dams drowning machines, he said, because they churn the water like washing machines, creating powerful currents. Throw a basketball into the water and it will spin there, caught for hours or days without escaping.

Communities across the country have dealt with this challenge, he said, many of them in new and creative ways. In other parts of the country, the Army Corps of Engineers has worked with outside engineering firms who specialize in dams and river restoration.

Wiles has researched grant funding and possibilities for modifying low-head dams. He has explored projects like the Iowa River Revival and talked with engineers in Boulder who developed strategies for lowering and altering dams to create white water for kayakers and to allow fish to move through.

Talking over coffee at Lickety Split, he looked out at the flood chutes that run through Mass MoCA. A mile and a half west, two dams cross the river near Brayton Elementary School and Notch Road, near the Cascades trail and the North Adams entrance to Mount Greylock. Another mile downriver, a third dam spans the water near the Blackinton historic district, where a 19th century settlement grew up around a large woolen mill, and Tourists Welcome, a chic hotel that opened several years ago on a property that had once been a standard roadside motel.

Wiles imagines rafting and trails that could connect the outer reaches of the city — near Tourists at the west end or Beaver Mill in the east — to the downtown. Much of the project would involve vacant city land, he said, and he has been talking informally with nonprofits and landowners along the river and meeting with favorable responses.

Every piece of land around the dams is open, he explained. His plan would displace no one, and he believes a restored river would add to the value of properties nearby, give local people new ways to have fun on the water, and bring new energy and life to areas beyond the system of flood chutes downtown.

“People have always seen rivers as travel and as power,” he said. “We want to think of the river as the power and health of the community. We’ll be using the river to re-power the community again.”

Wiles said he sees people in the community turning toward the water, from the Beaver Mill and the Eclipse Mill to the Roots Teen Center, from Mass MoCA to Tourists Welcome, from downtown business owners to arts and culture organizations to educational centers.

He sees a new generation of local residents, like him, turning to support the river.

North Adams natives Rosalyn Lincoln and Austin Thompson, for example, are co-founders of Mountain Warrior Conservation, and are leading river cleanups this summer, on third Sundays in June and July.

They have begun in May with a stretch near Blackinton and Tourists — after years of cleaning up trash informally themselves in their walks through the watershed. Both of them grew up here, they said over Zoom, and they have been cleaning up trails informally for years.

Through Mountain Warriors, they have already led collaborations with students at MCLA.

Collins, of the watershed association, said Mountain Warriors is making progress with cleanups in different places along the river, and HooRWA is coordinating now with partners from the South Williamstown Community Association to the Rensselaer Land Trust and Plateau Alliance.

Starting at the center

Rye Howard imagines green space downtown, parks and places to picnic.

“It would be so good for the town,” she said. “But if it’s going to happen, it has to happen right — or we’ll have another 50 years of ugly concrete walls and no connection to the river ecology.”

Howard is co-owner of a downtown business — the Bear & Bee Bookshop on Holden Street — but she also has scientific experience in environmental public health, epidemiology, toxicology and chemicals policy. She serves as s staff scientist at the Environmental Law Alliance Worldwide and has taught widely, including at the Brown University School of Public Health, Boston College and Boston University.

“If you take out the existing chutes, or remove part, take out the bottom, you have to put in sediment, because gravel would wash away, and you put in submerged aquatic vegetation so the plants start growing and will hold the bottom down,” she explained. “It’s a restoration project, and it would be tremendous to have a living river.”

Howard reviewed similar projects in Boston, Philadelphia and Providence, R.I., and alternative structures for floodwaters, in a conversation with Elena Traister, a professor of environmental science at MCLA who focuses on river systems. Traister also serves on the North Adams Conservation Commission.

Traister explained that in planning any changes to the infrastructure, the Army Corps of Engineers will have to consider how the river would change in response — how high the water would rise, how fast it would flow, what would happen in a 10-year flood or a 100-year flood.

She and Howard considered questions the engineers might take into account: Where can they widen the corridor to let the water disperse? Where can they vary and consider the slope and the depth of the banks? How can they guide and slow the speed of the water? How can they reinforce the banks?

Flood safety in the 21st century

Hoosic River Revival focuses on the 2 to 3 miles of flood chutes in downtown North Adams.

The Army Corps of Engineers built the chutes in the 1950s to mitigate flooding and shore up the mills along the banks, Grinnell said. But after 70 years, those concrete structures are becoming increasingly unstable.

Even from a practical safety point of view, she said, they need re-evaluation. Five wall panels have fallen, including the one on Willow Dell and another near Building 6 at Mass MoCA, and seven more are leaning. The infrastructure is old enough that it will become increasingly dangerous, especially as storms grow stronger and more frequent.

Now, Grinnell hopes to look at the city’s infrastructure from perspectives that didn’t exist in the 1950s.

“We don’t want them to put up more walls,” she said. “And they can’t now. We have new regulations for flood control projects: They have to take into account the community’s needs, the EPA, the Clean Water Act.”

Grinnell has been working to bring attention to the chutes for well more than a decade. She founded Hoosic River Revival in 2008.

But her vision began to take shape as long ago as the 1990s, she said, with a trip to San Antonio, Texas. Walking through its vibrant downtown, she learned that the city also had confined its river in the past; now the river had been restored and brought a new energy to San Antonio’s core.

She saw people sitting at restaurants along the water, walking on the banks, children playing. And she wanted to see that here.

Grinnell is not an ecologist, an engineer or a city planner, she said. At the time of her visit to San Antonio, she was working in sales for Storey Publishing. But she wanted new ideas for her own city’s river, and in the past 15 years, she and Hoosic River Revival have raised more than $2 million to look for them.

The group has learned from other cities modernizing flood control, Grinnell said. In conversation with Cindy Delpapa, who recently retired as program manager for riverways at the state Division of Ecological Restoration, Hoosic River Revival looked at the experience of communities from Denver to Providence that are reconnecting with their own rivers.

As the group considers new ideas for town planning and engineering, Hoosic River Revival has commissioned two studies already — in 2015 and 2018, one for the southern branch of the Hoosic and one for the northern branch — by Sasaki, an international architecture, planning and design firm.

In 2015, the group also worked with the Division of Ecological Restoration and the river and ecosystem restoration group Interfluve to study the possibility of setting up a research and educational center in North Adams to focus on urban river restoration.

Interfluve, co-founded by geologist and engineer Candace Constantine, has worked with river systems across the country — partly from an office in Williamstown, where Candace’s husband, Jose Constantine, serves as a professor of geosciences at Williams College.

The ecology of the river

In North Adams east and west of downtown, and in Williamstown and Pownal, Vt., great blue herons wade in the shallows. Mergansers paddle in midstream. People near the water may see bloodroot and trout lilies, brook and brown and rainbow trout, a young bald eagle winging upriver, even a migrating sandpiper in spring or fall.

The Hoosic is a cold-water fishery, said Lauren Stevens, a longtime board member of the Hoosic River Watershed Association. Stevens, a writer and naturalist, has spent decades on and along the river, exploring its natural sections and tributaries.

He also sees fish as one larger measure of the health of the river. The health of the fish connects with the quality of the water, the insects the fish eat, the birds and creatures that eat the fish. Today, trout are reproducing again naturally in some stretches of the river.

Justin Adkins, Joan K. Lentini photo

Justin Adkins, another HooRWA board member, serves as president of the local Trout Unlimited chapter and leads plant walks along the Hoosic with Collins, the association’s executive director. He spoke over tea with Collins and Stevens at Wild Soul River, the tea and herbalist shop he owns with his partner, Rebecca Guanzon, a few blocks from the river in Williamstown.

The health of the river has improved in the 40 years since many of the remaining mills closed, Stevens and Adkins said. Though losing the mills has had far-reaching implications for the towns along the Hoosic, a century and more of pollution also had far-reaching implications for the river and everyone who lives along it.

Some traces of industrial chemicals remain, Collins said, but the water quality has improved to the point where the river is safe for paddling and fishing and casual play, as long as the currents are also safe. HooRWA monitors the water and tests for E. coli, microinvertebrates, chemicals and salt runoff.

“The upshot is that the health of the river is good,” Collins said.

But the water temperature is rising with climate change, and Collins, Stevens and Adkins are considering new variables. Shade can affect the water temperature significantly, and they are concerned about trees along the riverbank — planting new ones, as well as keeping healthy mature trees and letting them grow.

Building along the banks

They are also concerned with pavement. The flood chutes are heating the river even more quickly as shallow water spreads over hot concrete. Stevens sees challenges in balancing the health of the river and the infrastructure around it.

Along some stretches, people in the past have built in the flood plain and sometimes directly on the riverbanks.

“It’s like Amsterdam,” said Howard, the bookstore owner. “The buildings go straight down to the water.”

And power from the river was key to the city’s early development as a manufacturing center.

“We can think about the environmental history of the river before it was straightened, and before the concrete chutes went in,” Traister said. “The river was more naturally flowing. Industrialization … led to water power for the mills. And so much was built right next to the river — sometimes, like Mass MoCA, right on the river.”

When floods in the early 20th century damaged houses and businesses, Traister said, the effects did not surprise people who understand rivers and watersheds, but they often came as a surprise to people living in those houses. After devastating floods in the 1930s and ’40s, many local people saw the river as a danger — and the new flood-control chutes of the 1950s as protection.

Many of the city’s residents in that era worked in local mills, and with the city and the mills dumping into the river — sewage, chemicals and more — people living hear the river saw other dangers. Some in North Adams can still remember when the river changed colors depending on what the paper and textile mills were dying that day.

“It smelled, and it looked gross,” Traister said. “But times have changed.”

Stevens has seen a change in the community’s relationship with the river. Even before his time with HooRWA, going back decades, he worked with groups trying to keep people from dumping illegally — trash, tires, shopping carts. And he said he has seen improvement over the years, though some dumping still occurs.

In early May, a pipe broke and dumped raw sewage into the river, reminding him another element of North Adams infrastructure that needs work — the city’s stormwater and sewer system.

“The sewage spill was horrific,” Adkins said.

But one of the worst effects, he added, was that it fed “the mentality that the river is dirty in the first place.

“You’d read the comments online, and people were saying, ‘It’s disgusting anyway,’” he explained. “When you think that, leaving a can or a mattress on the bank doesn’t feel as hard. But there’s a mentality that it’s not clean over all, and that’s not the case. Don’t drink the water or eat the fish. But touch the water, wade in it, float on it, swim.”

Living with the river

Adkins and HooRWA are looking for a balance in the health and safety of the people along the river, the economy and life of the city, and the ecology of the land — within the dictates of plain physics, geology and the ways water naturally moves.

“How do we support the river living the life moving water needs to live?” he asked. “A river is supposed to move.”

Adkins said he sees natural shifts of the river in its bed near his house. Going down to fish, he will see new shoals, snags, a fallen tree carried downstream.

“We’re not allowing the river that in so many areas,” he said. “We’ve built close to the water.”

He said he recognizes and respects the people and housing and businesses along the parts of the river with flood chutes and lowhead dams, as well as in the areas where the river is more natural. And he shares a concern for North Adams and for thriving businesses near the water that, he said, may not be valued by everyone in the community.

“I want to talk about economic class and what this means,” he said. “The health of the river and the health of the people who live here — we’re looking at all of that. ... This is for all of us to live together -- we’re living with the river. It’s a give and take -- how do we support each other?”