Arts & Culture February-March 2023

Artists rooted in Tibetan traditions

Group show at Williams pairs historical, contemporary works

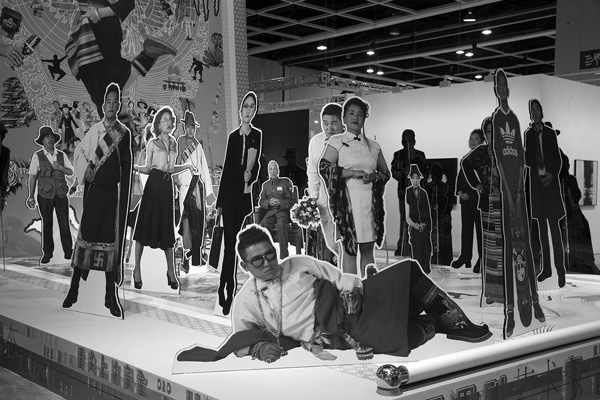

Gonkar Gyatso’s “Family Album” is among the works included in “Across Shared Waters,” a new group show at the Williams College Museum of Art. The exhibit pairs traditional Tibetan art with work by contemporary Tibetan artists from around the globe. Photo courtesy of Pearl Lam Galleries

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

WILLIAMSTOWN, Mass.

A Buddha sits with one hand touching the earth, and his body is formed from leaves and flowers.

Lama Tashi Norbu sees the rings of petals in two forms at once — the lotuses of his Tibetan tradition and the tulips of his new home in the Netherlands.

“We have to grow out of this muddy water,” he explained, “like the lotus grows in this muddy water, where the world is sufferings and happiness — everything is in it, like that — and then [we are] surviving through it.”

Norbu was speaking from his own museum and cultural center, the Museum of Contemporary Tibetan Art in Emmen, near Amsterdam. He is an internationally known artist trained in Tibetan thangka painting and in Western art.

He will come to Williamstown this spring as an artist in residence as part of “Across Shared Waters,” a new group art show at the Williams College Museum of Art. And in February, he will join in a conversation about traditional Tibetan art with other Tibetan artists around the world, from Australia to America to Tibetan areas of China.

Many of these artists have left Tibet, or have never lived there, because their home country and culture are under threat, and Norbu said he sees a vital need to create spaces to preserve their culture for the future.

“We have to do it, Tibetans,” he said, “for our culture to survive.”

A gift to three colleges

The traditional artwork in the Williams exhibit comes to the college as a gift from Jack Shear, an artist, photographer, curator and collector in New York City and Spencertown, N.Y. Shear was the longtime partner of contemporary artist Ellsworth Kelly, who died in 2015, and he now directs the Ellsworth Kelly Foundation.

Last spring, Shear made a gift of traditional Tibetan artwork to Skidmore, Vassar and Williams colleges, said Ariana Maki, the associate director of the University of Virginia Tibet Center and Bhutan Initiative.

The three colleges asked Maki to come up and look through the collection and then to guest-curate exhibits at Vassar and now at Williams. She also will co-curate one at Skidmore.

“What impressed me about the Shear collection is the … sheer number of works available for us to draw on,” Maki said in a Zoom interview from Charlottesville, Va. “They touch on a number of aspects of Tibetan philosophy and practice.”

Through them, she has brought together a wide-ranging group of Himalayan and Tibetan contemporary artists who invoke the traditions and art forms of their homelands while creating their own work that she finds new, distinct and compelling.

Maki said the Williams show begins for her in four thangkas, Tibetan Buddhist paintings. The ones in the exhibit were painted 100 to 400 years old, though the form goes back more than 1,500 years. Traveling monks would bring them to towns and villages, to teach.

For her, these paintings open ways into contemporary themes — the forces a family can put on the people within it, or society on one person, or traditions on people who carry them. And she turns to contemporary artists to ask how people navigate these forces, past and present, and the sense of place they have in the world.

‘Be the flower’

Norbu said that in his painting, he looks to some of his earliest experiences in the West, learning a new place. He and his brothers, two of them monks, would travel together, opening art exhibitions and making sand mandalas, and people would bring them flowers. And he struggled with the idea that people had cut flowers as a gift.

“For us, a flower is a living substance,” he said. “We wouldn’t do that in Tibet. … But we tried to look at the intentions of the people bringing them.”

So he thought about adapting to a new culture, and about an idea in Tibetan culture and poetry: “Be the flower, not the bee.”

“The lotus … survives through the deepest part of the water,” he said, “until [he reaches] the surface of the water, until he blooms. We grow from this chaotic life, growing up, and then shine beautifully like that to the bees, and then they come to us.”

So he combined these ideas, just as he combines being a contemporary artist and a monk.

“We don’t have to search somewhere else, like the bee does,” Norbu said. “The happiness is lying within you. And then the action has to be like the bees: We are sowing the seeds for things to grow.”

Norbu’s painting takes the form of a Shakyamuni Buddha, the fourth Buddha that has come to this world, who also appears in one of the thangkas.

The painting chronicles the Buddha’s past lives, Maki said, and the transformations he has come through to become a Buddha, to learn generosity, compassion, time. Many Tibetan Buddhists believe each person has had hundreds, thousands of previous lives, she said, and from them, cumulative experience will determine their next rebirth.

“Until now we have had four Buddhas,” Norbu said, “and we are supposed to have a thousand Buddhas on this earth, to help all beings. They say until all living beings are enlightened, Buddhas will come to this earth, so the world is not yet finished. So I chose this Buddha touching the earth.”

From Tibet to a wide world

In the Williams show, Norbu will set his work in conversation with other artworks. They span many styles and media, from abstraction to Gonkar Gyatso’s life-sized photographs of living Tibetan folk, collaged into a global and often urban “Family Album.”

Maki sees Gyatso and others, like Karma Phuntsok, speaking from an earlier generation of contemporary artists that have had a global influence and have broken a trail for Tibetan artists around the world.

“They have each taken a different path to their ways of working and where they live,” Maki said. “They have catalyzed one or two generations of artists in the Himalayas who are experiencing their own successes now thanks to the worldwide attention that Gonkar brought and others brought.”

Like Norbu, Gyatso received formal training in thangka painting, Maki said, and like Norbu, in his work here he also responds to the Shakyamuni Buddha. But while the traditional thangka shows Shakyamuni surrounded by his past lives, Gyatso’s Buddha is surrounded by what’s happening now, what he is experiencing in this life. The setting is urban.

“To me, it was speaking to a lived present but also an uncertain future,” Maki said. “When the Buddha was in his past life, he didn’t know on what trajectory he would ultimately land.”

In answer to still more current events, Gyatso has also offered her a work he created in the pandemic, in October 2021, surrounded by experiences he had while living in China amid the rise of Covid and the resulting lockdown. Maki said she feels in it a very human response to a very surreal and often overwhelming situation.

Phuntsok, like Norbu, blends ritual and natural elements from Tibet and from a distant place where he now lives. He centers implements that often appear in the hands of deities, and today in the hands of human teachers, Maki said. And around them he sets patterns of concentric circles often represented in Aboriginal arts in his new homeland of Australia.

He is representing two streams that have come together in his life, Maki said. She sees echoes, resonances and a meditative quality in his rings of concentric circles, mandalas and circular walking paths — and in the state an artist might be in to create them, the repetition and cadence of creation an artist might experience.

Bright color and abstraction

Abstraction has a place in this visual conversation, Maki said, looking closely toward Pema Rinzin’s vivid colors and patterns.

She first met Rinzin in 2008, when she was serving at the Rubin Museum of Art in New York, which is dedicated to the arts and cultures of the Himalayas. He was an artist in residence, creating paintings live in public for anyone to see.

“Pema was trained by some of the foremost master artists in Dharamsala, India,” she said, “and so his brushwork is absolutely sublime. It looks like it is just a flat application of color, but it is the addition of hundreds and thousands of brushstrokes, just done in such a masterful way that it gives the appearance of a flat, uniform surface, but the amount of time and attention to detail in the skill of wielding the brush is phenomenal.”

Since then he has been teaching, she said, and working in more abstract forms, in dynamic and varied compositions that often travel internationally.

“He has two works in the show, ‘Abstract Sound No. 4’ and ‘Bird Mandala,’ ” she said. “And if you put them next to each other, you wouldn’t think they were done by the same artist. His work is wide ranging and thought provoking.”

She traces fine detail in his washes of deep blue, cornflower blue and camel-dun — goldwork like the symbol of a lotus on a monk’s robe, golden leaves and petalled flowers found on textiles, a swirl on dark green like a cloud-scroll motif.

“What made me think of Pema is how his life in some ways is emblematic of what the entire exhibition is trying to do,” she said. “He’s so well grounded in and thoroughly versed in traditional techniques, which are … awe-inspiring, quite honestly, and he’s also deftly expressing himself in these innovative ways.”

Mandalas and worlds beyond

With a storm-cloud churning, Marie-Dolma Chophel sets her work in motion with a force of energy in color.

Maki came to her thinking of another traditional work in the collection, a meditational diagram used for people initiated into a practice. The work recalled Chophel’s for her in its use of space and its use of senses.

“Mandalas tend to give a mental map, a guidance for the mind,” she explained.

Someone meditating will think of aspects of the environment and the body in very precise ways. They will envision the world around them, conjuring sights and sounds and smells and acts. And Chophel’s work gives her a cosmic sense of perspective.

“We’re working through space and our ideas of ourselves,” Maki said. “We’re here on this earth, and the more that we learn about the earth — we are a very rare space that can foster this diversity of life, diversity of cultures. The more that we look out through James Webb or Hubble or any of these telescopes, we are not finding others like us.”

In Chophel’s work, she feels a sense of place as physical and mental, abstract and real at the same time.

She compares that vision to meditation as a practice, which aims to see each living element, like the bud of a flower, as real and complex and alive — and at the same time, to recognize when what someone is seeing is not part of the flower, but part of themselves. They learn to tell the difference between the opening petals and calyxes and their own experience or perception.

Describing her work for Maki, Chophel explained: “My idea was to create a space that would give a sense that all elements [earth, wind, fire, water and space] are in constant conversation — interconnected and interdependent — whether we think of the outside world or the conditions for the existence of sentient beings, both physically and on the level of consciousness.”

Chophel embeds her artwork in the natural world — and in the world beyond the natural world, Maki said.

“Our internal worlds … inhabit the natural world,” she said, “but we also have the capacity to go far beyond through our imaginations.”

“Across Shared Waters: Contemporary Artists in Dialogue with Tibetan Art from the Jack Shear Collection” will open Friday, Feb. 17, at the Williams College Museum of Art. The show runs through July 16. Admission is free.