Arts & Culture April 2023

Goya’s passion brought to life

Spanish master’s images inspire a dance troupe’s evolving new work

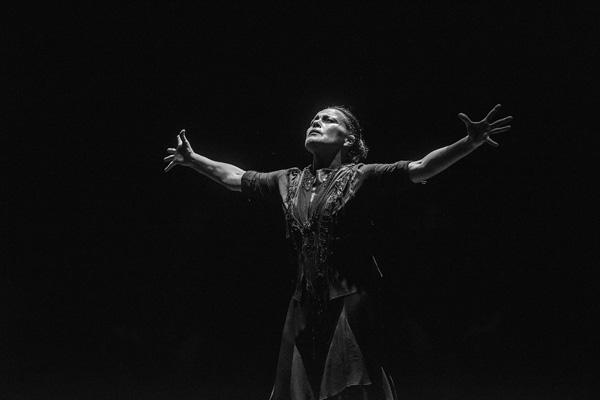

The dance company Noche Flamenca will offer a work-in-progress preview of “Searching for Goya” on April 8 in the ‘62 Center at Williams College. The work draws its inspiration from the turbulent, sometimes dreamlike images captured by the Spanish master Francisco Goya in the early 19th century. Photo courtesy of the ‘62 Center at Williams College

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

WILLIAMSTOWN, Mass.

A woman turns in the wind, her cloak blowing around her.

She is up on the ridge looking across the valley. Washes of ink show her hair streaming, her shoulders sloping and her body coiled with energy. She is shifting her weight forward, her knee bent, and the light catches on her bare foot on the earth.

With her back to the frame, she could be dancing. And if she completed the movement, how would she spring from here?

Martin Goldin Santangelo and Soledad Barrio are asking, from a dance studio in New York City. They are looking at an 1824 painting by the Spanish artist Francisco Goya, a miniature watercolor on ivory. On the wall behind them, in a black-and-white photograph, a woman spins in a flamenco step, her skirt and her shawl trailing around her in the air.

Santangelo and Barrio are the founders of contemporary dance company Noche Flamenca. They live and work in New York, though they have performed widely in Spain and around the world. And they say they are finding deep overlaps between their language of dance and Goya’s language in composition.

This month, Noche Flamenca will give a work-in-progress preview of “Searching for Goya,” which explores through flamenco how Goya responded to the turbulent social and political changes in the world around him. The performance, a series of vignettes with original choreography and live music, begins at 8 p.m. Saturday, April 8, in the ’62 Center at Williams College.

Santangelo and Barrio are husband and wife and longtime artistic companions and co-choreographers. Barrio has performed around the world as a Bessie Award-winning dancer of flamenco, and Santangelo, who also has long experience as a performer, is Noche Flamenca’s artistic director.

And he has fallen in love with Goya, Barrio said, laughing.

Barrio and Santangelo both find his work viscerally powerful and, for an artist of the early 19th century, startlingly modern. Goya defined the rules of surrealism, they said. His work can be dreamlike, satirical, phantasmagoric and unflinchingly human.

Santangelo has been researching him for two years now, including on quiet days at the Williams College Museum of Art and the Clark Art Institute, as Noche Flamenca has created new movement and choreography and music inspired by Goya’s paintings and prints.

Goya first came to them almost casually, Santangelo recalled as he and Barrio joined in a Zoom interview on the night of a spring snowstorm.

Amid the pandemic, he was talking with a lighting designer about how to choreograph movement from a painting or a drawing, and the designer sent him an image of one of Goya’s later works.

“From that one image, it started growing and growing and growing and growing,” Santangelo said. “I started seeing the importance of Goya, and what he is. And I had no idea, which is unfortunate, because I think he should be in every single person’s life, whether we want him or not. He’s like Shakespeare or Aristotle — he is everywhere.

“We should be more aware of it and learn from him.”

Discovering Goya’s late works

Though Goya spent decades as the royal court painter of Spain, Santangelo said, later in his life he incisively considered the beauty and brutality of his home country.

Santangelo came to Goya’s work first through a series of prints of etchings and aquatint called “Los disparates” (The Follies). These late works, which weren’t published until several decades after the artist’s death in 1828, combine dreamlike, sometimes troubling images with a sense of absurdity, nonsense, slang, and rough and colorful street talk.

“In his paintings, you immediately begin to imagine,” Barrio said, as Santangelo translated for her. “There’s usually a before, present and after, except in a few that are more abstract, what’s considered abstract painting today. They have no before, no time, no place. And you start imagining.

“His images have a lot of movement. From a Spanish perspective, there hasn’t been a lot of attention given to Goya in dance, not as much as he should have been, especially in flamenco.”

How do they translate the soul and expression in his artwork into their own languages of movement? Santangelo started out playing with projections and visual imagery, he said, and over time he has been steadily paring them away.

They are not narrating Goya’s paintings or re-enacting his scenes, they agreed. They are asking themselves what Goya wanted to express, often in gut-clenching tides of feeling — compassion, intimacy so close it can blend two bodies together, terror, longing, solitude. And then they are asking each other what, within their language of flamenco, expresses those depths in his work.

They recall a painting originally called ‘a dog’ — and then ‘a dog half-drowning.’ It comes from the black paintings, a set of 12 or 13 scenes Goya painted on the walls of his house in Madrid. This one, rare for him, fills a long vertical rectangle. A small dog is looking up at the very foot of the frame into a vast red brown space above.

For Santangelo the work conjures strong feelings of longing, desire — a vulnerable creature desperately looking for something out of the frame in an endless empty world. In his choreography in these new scenes, he often begins with Goya’s composition, he said, his use of space, and the movement and body language of his central figures, because he finds them intensely expressive in themselves.

In this vignette, a guitarist is playing music inspired by Miles Davis’ version of “Some Day My Prince Will Come,” and the sound is inflected with longing and isolation. He is accompanying a dancer, a singer and a percussionist.

“Usually they’re all together, and the guitarist would be like this,” Santangelo said, turning toward Soledad and looking into her eyes from a hand’s breadth away. “But I put the three men high in the air, on a platform.”

He looked upward as his hands mimicked strumming chords. The guitarist is trying to communicate, to say, “Am I in the right rhythm? Am I in the right tonality when you sing — am I with you?” And the people he needs are all at a distance.

Abandoning a privileged life

In much of Goya’s later work, Santangelo finds that kind of deep vulnerability. Winged people glide in the night sky. Carnival figures walk on stilts, and women in shawls huddle together on a tree branch high up, as though for shelter.

In these dream visions, Santangelo sees him questing. He sees a soul seeking rest who has pared his own life away to find truth. And he finds that integrity all the more astonishing from the heights Goya had reached.

“He was a rock star,” Santangelo said. “He was the painter for the most powerful people in the world, for the kings of Spain, France, Napoleon, Napoleon’s brother — the most important, the richest people in the world. …

“He was celebrated. He was sleeping with the Duchessa de Alba, who was the Kardashian [of her time] — a woman who was extremely learned, who slept with a lot of men. She was culturally cultivated, and she was in love with him. …

“In other words, he had everything -- the hottest women, the best-paid [position], the post powerful people in the world, everything. And he gave it up. He chose to give it up. He chose. It’s hard to understand that.”

Thinking it through, Santangelo asked his younger daughter to imagine the most powerful person in the world today. She named Beyonce.

“So it would be like Beyonce performing in a nightclub in your town for 20 bucks for the rest of her life,” he said. “And looking for something. Looking for something. Trying different types of things with her music, trying and trying, and people laughing at her, going ‘What the f--- are you doing?’”

Why did Goya walk away from that privileged life? Because of his values, Santangelo said. He valued common people, and he painted them for the second half of his life. He valued internal visions, and he valued a different society.

He had navigated through horrific and brutal conflicts in his country. France invaded and ousted the Bourbon kings of Spain, and Goya survived under Napoleon. The Spanish kings re-invaded and defeated the French, and he stayed. And after that feat of diplomacy, he still left the court and all the power he’d held onto.

“He gave it up because he wanted to paint,” Santangelo said, “because he wanted to paint honestly, and he wanted to keep diving into new techniques. Which is mindblowing. It’s something nobody does. I’ve never heard of it.”

“It is profound, what we see in his images,” he said. “And flamenco can represent or express what he is talking about. The rawness of flamenco, the comic, the pathetic, the profound, the tragic part of flamenco, has a lot to do with Goya’s later works.”

Capturing violence — and beauty

Goya created several series of prints and paintings late in his life, Santangelo said. Some of them are surreal and shadowed. Some sketch everyday life with a depth of compassion that surprised him.

Some show the peninsular war between France and Spain with almost photojournalistic reality, along with the sheer violence of bullfighting. Some hold a clear satiric light on the Spanish Inquisition, the abuse women live through, injustice against the poor.

“In ‘Los caprichos,’ Goya takes a satirical plunge into straight-out criticizing the morality of the day, the customs of the day, the church, the Inquisition, the disparity of economics,” Santangelo said. “That was an extreme satire.”

He turns to the image of a prisoner of the Inquisition riding a donkey through a crowded street. Captors circle on horseback, and the mob is jeering. The figure wears an iron throat band with a metal bar attaching to manacles at the wrists — a device U.S. law enforcement agencies still use today.

“You can see the humiliation,” Santangelo said, shaking his head in sadness and in admiration of the power of the image. “And the crowd is getting off on it. Those people on the horses looking so proud of what they’ve done, and their control, … and the light is amazing. It’s incredible, it’s horrible, and it’s relevant.”

Goya chronicled the peninsular war in a series of 120 plates. Santangelo has a book of the whole series, and he finds it deeply important work — and so intense he can only move through it gradually.

“I have not once in the last two years been able to sit down and go through the entire series,” he said. “I just can’t. It’s too much. It’s so devastating -- the heartache within images of war, violence and brutality, what one human being can go through. I’ve never, ever seen or experienced that, how he makes us so damn aware how brutal they are to each other.”

In many of these images, Goya is capturing what he sees around him. But in their choreography, Santangelo and Barrio are most drawn to his more dreamlike, abstract work. They are not shaping their show around Goya’s life story, they said, but around his visions.

In one of “Los disparates,” four bulls rain down, floating in the sky. Santangelo and Barrio choreograph the beauty of these animals, and the celebration of them, and the power in the apparent contradiction as Goya calls attention to their strength and grace, because they’re floating and yet they’re so heavy.

In his research, even in painful images, Santangelo would find himself noticing Goya’s compassion. He wondered why Goya so often painted and sketched women, he said, regular women, not the royal women of his court-painting years.

He said he learned that Goya was the first Western artist to begin painting women who were not saints, or of royal blood, on a regular basis.

“He began to paint women and celebrate them, and show the horrors of what happens to women in war, in poverty, through prostitution,” Santangelo said. “He’s global, Goya, but he’s also specifically Spanish.”

Barrio, from her own Spanish perspective, has also relished getting to know Goya in new ways.

“A lot of people my age in Spain, we know of Goya,” she said. “But we know mainly the royal paintings, the pretty ones. I didn’t know Goya like this. And most of the people in the company, who are cultivated people and open people, they’re saying ‘What? That’s Goya?’ We know Dali very well, Picasso, Miro, but I didn’t know this man was like this.”

A moment at death’s door

Santangelo said that in his research, and in the dance company’s performances, they are still making new discoveries. And when he came to the Williams College Museum of Art and the Clark Art Institute to sit with originals of Goya’s prints, he made a discovery that shook him.

He had learned that Picasso took the composition for his monumental painting “Guernica” directly from Goya. (The painting, one of Picasso’s best-known works, depicts the suffering wrought by the bombing of the town of Guernica in 1937 amid the Spanish Civil War.)

When Picasso was commissioned for the work, he had three weeks to turn it around. So he went to a Goya print called “Ravages of War.” Santangelo said he had seen the reference in one of Picasso’s letters.

Santangelo held up the Goya print -- bodies sprawled together, heads and limbs tangled in a central pyramid. He compared it with “Guernica” — the same diagonals, the same circles, the same central triangular form.

Here he had the chance to sit with the original print for hours, he said. And up close, he saw in Goya’s work something horrifying to him, and new, something that undercut any possibility of falsely glamorizing war.

“The thing about this,” he said, “if you look carefully, they’re still alive. And they’re about to die.

“It’s that one moment. That explosion just occurred, [decades] before the Guernica explosion, and they’re right at that moment, between that last,” — he drew a sharp breath — “there’s a last gasp, there’s a little baby who’s” — he reached out one hand and clenched the other — “the last clutch. And you can see their hands are still tense, not dead.”

The genius of the work that Picasso saw, he said, was the relevance of time: “When that bomb went off, which is a second before the painting is painted, you’re in the moment of the painting, and one moment later: death.”

And that heightened moment brings him back to the dance and the music and the reality of people moving intensely together on stage.

“So this started taking me to the relevance of flamenco,” he said. “Because the relevance of flamenco is the desperate cry of humanity for social justice, for economic justice, for freedom, societal or personal. And it’s a moment.

“It’s usually a visceral moment that you get to. And it happens again and again and again with Goya -- these moments, these visceral moments, right before something happens, right after.”

And the dancers are holding those moments in rhythm, with guitar and percussion and song. In flamenco, each artist, each dancer, singer and performer can improvise like jazz musicians, Barrio said.

“We all know our vocabularies, and we all have our individuality,” she said. “In flamenco, each artist can move from a personal perspective … and the movement gives birth to what you feel.”