Arts & Culture May 2023

Classic text, contemporary context

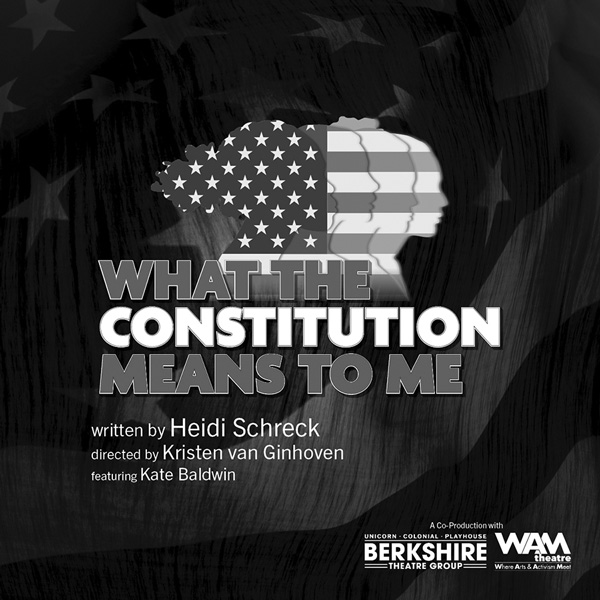

WAM Theatre presents ‘What the Constitution Means to Me’

The cast and crew meet in late April for the first rehearsal of WAM Theatre’s production of “What the Constitution Means to Me,” which opens May 18 at the Berkshire Theatre Group’s Unicorn Theatre. Courtesy photo

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

STOCKBRIDGE, Mass.

As a teenager explaining the meaning of the Constitution in debate competitions around the country, Heidi Schreck sets an idealistic tone.

“The Constitution is a living document,” the young Schreck argues. “That is what is so beautiful about it. It is a living, warm-blooded, steamy document.”

And as an adult, as a woman, she asks with a deeper understanding: What world could we imagine if that could be true — if it could be true for her, and for everyone?

At a time when rights for women, gay and trans folk and people of color are facing new challenges, and when violence against them has only intensified the pandemic-era sense of isolation, Schreck becomes increasingly aware that a document she has spent years defending has never included her.

“Our bodies — our bodies — had been left out of this Constitution from the beginning,” she says in her Tony-nominated and Pulitzer-Prize-finalist play, “What the Constitution Means to Me.” The show opened on Broadway in 2019 with the playwright in the lead role as herself.

This month, WAM Theatre will bring Schreck’s exploration of the Constitution to the Berkshires, becoming one of the first theater companies in the nation to obtain the right to stage its own production of the show. In partnership with Berkshire Theatre Group, it will have performances May 18 to June 3 at the Unicorn Theatre in Stockbridge.

“Everyone in the theater knew about the play,” said Kristen Van Ginhoven, WAM’s artistic director. “It has been so popular. … But the rights have not been available while the play has been running on Broadway.”

Associate director Talia Kingston got the local company on the list to hear when the rights would became available, Van Ginhoven said, and when the possibility opened last fall, WAM applied within the first 15 minutes. When she got in touch with Berkshire Theatre Group, its artistic director, Kate Maguire, responded immediately.

“I phoned her it and said, ‘So, would you like to co-produce “What the Constitution Means to Me?”’” Van Ginhoven said, laughing. “And she said, ‘Yup — we’ll work out the details later!’ It was such a no-brainer. … So we were one of the first to get the rights, but it’s being done everywhere now.”

Two-time Tony Award-nominated Broadway actor Kate Baldwin, known here from many performances on the Berkshire Theatre Group stage, will take the role of Schreck, and award-winning Berkshire actor Jay Sefton will join her as the Legionnaire. Van Ginhoven will direct.

As they re-create Schreck’s teenage and adult debates, the play gathers them together with real debaters from rising generations. From the Berkshires, WAM has cast Zurie Adams, a passionate activist and a senior theater major about to graduate from Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts, and an alternate debater, Izzy Brown, a Pittsfield high school student and performer and equally fervent activist in the community.

Evolving as times change

Schreck begins the story in her own past, Van Ginhoven said. As a teenager, the playwright raised money for college by competing in constitutional debates at American Legion halls around the country.

And looking back as a woman, she began to reckon with the document’s strengths — and its challenges. Some of what it leaves out becomes adamantly clear, Van Ginhoven said, as soon as Schreck looks for it.

“There are 4,500 words in the Constitution, 27 amendments, and the word ‘woman’ is never once mentioned — not once,” she said. “We’re completely erased from it.”

As Schreck examines the structures that have defined democracy in this country for 250 years, the play becomes a deeply personal story of family survival through generations of trauma — and a fierce response to events in the daily headlines — as well as a new debate on how to build for the future.

She also adapts to the shifting present. Schreck has given the actors and director space to respond to the rapid changes in national debates and people’s everyday lives, Van Ginhoven said, and with every new development in the debates surrounding abortion rights and the Supreme Court, her message deepens.

“That’s the depressing and the astonishing thing about the play,” Van Ginhoven said. “I think it will remain timely for awhile. And she has said … in interviews that no matter what has been going on over the last few years of performing it, it always seemed prescient.

“It always seemed that the thing she was talking about was what was going on in the news that day. Because it captures the last 250 years of history, and what’s going on about women’s rights and women’s reproductive health is just ongoing.”

Establishing basic rights

In the opening, through Schreck’s teenage eyes, she shows her longtime fascination with the Constitution’s strengths — the ways it has survived and adapted far beyond the future the founders could see. They recognized a living document’s need to grow, she argues in the play, and created room for it: “Thomas Jefferson himself said we should draft a new Constitution for every generation.”

She focuses on the Ninth and 14th Amendments, which have both come into play, she says, to pass laws that have upheld civil rights and women’s rights, including a woman’s right to choose.

The young Schreck defines the Ninth Amendment with fascination as the amendment that rights exist beyond the words on the paper.

“I’d like to talk about the most magical and mysterious amendment of them all,” young Heidi says in the play. “Amendment Nine says: The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.’”

She sees the writer standing in a vast unmarked space — creating room to move and breathe for the unknowable time ahead, and allowing potential for human connection.

“This space of partial illumination, this shadowy space right here: This is a penumbra,” she says.

And Schreck sees immense power in this fluid space. Van Ginhoven recalled a conversation Schreck held at the 92nd Street Y with a constitutional scholar.

“When she encountered Amendment Nine as a teenager, she fell in love with it, because it was the invitation to be involved,” she said.

And then the 14th Amendment, in the first part, affirms that every person born here is a citizen, that states cannot take away rights the federal government has given, that every person has a right to equal protection under the law. Schreck acknowledges vital gaps here and at the same time sees vital tools for ensuring freedom.

Less than fully equal?

The 14th Amendment has played a role in many arguments for civil rights and women’s rights, Van Ginhoven agreed, though still it has not protected Native peoples, immigrants and many more.

When the Constitution says every person is guaranteed a right, people of color, women, immigrants, people of all abilities and identities and orientations all should be included, she said. And in practice, many people often are not.

Schreck grapples with the reality that the Constitution is a document drafted by a group of white men, Van Ginhoven said — the same men who were talking about equality as a central ethical principal when they had enslaved people working on their plantations and in their houses.

And as the play deepens, Schreck grapples in increasing intensity with the vulnerability people face when they know the law doesn’t protect them.

“So what I’m trying to understand now,” the adult Schreck asks in the play, “is ... what does it mean if this document offers no protection against the violence of men?”

She gives a bleak and clear accounting of the violence she sees on the rise in the United States, first in numbers.

“Since the year 2000, more American women have been killed by their male partners than Americans have died in the war on terror — including 9/11,” she explains. “That is not the number of women who have been killed by men in this country; that is only the number of women who have been killed by the men who supposedly love them.”

And then she underscores her statistics with real lived experiences. Three generations of her family have known what that violence means — up close, daily. Her mother and her aunt have survived and had the courage to break the cycle before her generation.

Confronting abuse, on stage and off

WAM too is reckoning with the lived experiences of people the Constitution fails to protect. (WAM stands for Where Arts and Activism Meet.)

Van Ginhoven said the theater company has been talking with Janice Broderick, executive director of the Elizabeth Freeman Center, which will receive a share of the proceeds from these performances. The nonprofit center serves victims and survivors of domestic abuse and sexual assault throughout Berkshire County.

Broderick “has shared many times the increase in domestic violence calls that Elizabeth Freeman has been receiving over the past few years,” Van Ginhoven said. “Especially during the pandemic, home was not a safe place for so many people.”

In addition to making a financial donation to the Elizabeth Freeman Center, Berkshire Theatre Group and WAM will lead a drive to gather household items to benefit the families served by the center — families who often have had to leave everything behind to be safe.

“Four women are murdered every day in this country by a male partner,” adult Heidi says in the play. “One in four girls will be sexually abused before they turn 18. One in four women will be raped by the time they are my age now. And 10 million American women live in violent households.

“My mom lived in a house like this. So did my Grandma Bea.”

Her younger self asks why her grandmother did not leave a violent and abusive man and protect her mother and her aunt and their siblings. She knows her grandmother as strong, powerful, viscerally and actively loving.

“I think as a middle-aged woman she is still grappling with that,” Van Ginhoven said. Through the play “and including the audience in the dialogue, she comes to an answer.”

For anyone facing daily life-threatening violence, she said, leaving is a hard and complex process. Often the person under threat has few resources and no safe place to go. And making the attempt to leave the abuser can be deadly.

In the first part of the play, Van Ginhoven said, she sees Schreck grappling with that “and coming to some kind of healing with her past so that she can step into the future.”

Basis for a brighter future

Toward the end, the play moves into a new active rhythm, as Schreck and her new generation of debaters come together to consider what real change can look like. She sees high stakes, Van Ginhoven recalled from the talk at the 92nd Street Y.

“We are in a moment where we cannot rely on the Supreme Court to be making decisions in the best interests of the country,” Van Ginhoven said. “And so the state supreme courts have to step up.”

But the people ultimately are supposed to be the strongest voice.

“We are able to create what our future is,” Van Ginhoven said. “We can’t forget that.”

Even in this year of constant challenges and debates, she has seen a growing strength in voices rising, as people defend a woman’s right to care for and protect her own body, even in states where she might not have expected it.

“The country does not want this,” she said. “We have had the midterms, Wisconsin, Kansas, Michigan. We have had proof over the last year that when push comes to shove, people do not want to inhibit a women’s right to choose.”

And preparing for the play has led Van Ginhoven into new research, she said, and has pushed her to think about the nation’s founding documents, and about engaging with community structures on every level, with new eyes.

“We have one actor who auditioned for the debater … who is Chinese and wants to become American, and she is passionate about the play because we have a Constitution,” Van Ginhoven said. “We have a document that gives people rights, we have a democracy — and that was more than she has grown up with. … It’s eye-opening and a potent reminder: Yes, it is flawed, it’s supremely flawed, but we’re lucky to have it.”

She said she has been thinking with a new sense of expansiveness about what Constitution says — and could say — as the play’s debate invites her to. With a few exceptions, she said, the Constitution is framed around negative rights, defining what the government can’t take away. But other countries have written constitutions based on positive rights — the right to vote, the right to an education, the right to food, medical care, housing or a job.

“I think about my own journey of activism,” she said, “and as a Canadian who has become also an American citizen, and I think about how my whole WAM journey has led to being part of telling this story — of this recognition that nothing changes without us becoming active in the civic world, how civic engagement and voting and advocating for our rights is the only way things will change.

“And I feel it: There’s an apathy around that, because of a lack of faith in our government and in our systems. It’s like, ‘Why bother? Everything is so messed up.’ And this play has provided me hope that there is value in the American democracy and there is value in civic engagement.”

Above all, she feels a call to action.

“I love intellectual debate,” Van Ginhoven said. “And I love putting on plays that feel like an experience, when the audience leans forward in their seats and is invested in the outcome.”