News & Issues April 2022

A gerrymander for the House?

New York’s new maps draw criticism while boosting local incumbents

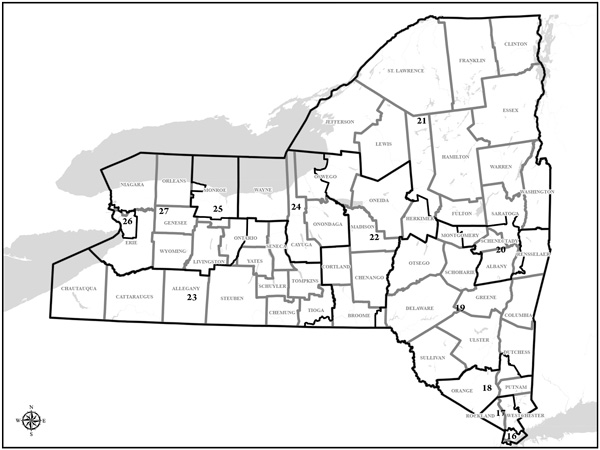

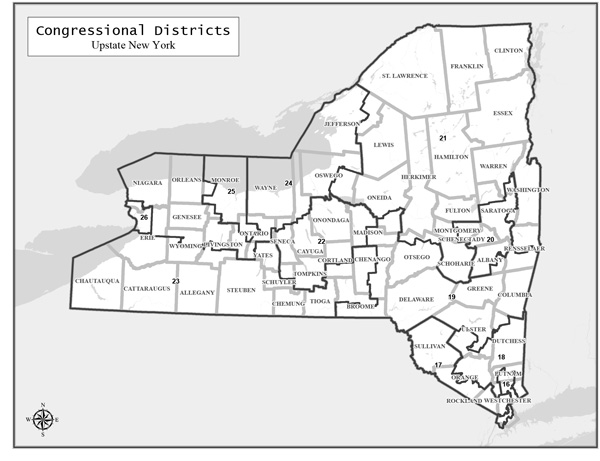

New York’s Democratic-controlled Legislature adopted a new map (below)for upstate congressional districts, right, that shuffles the political terrain of the upper Hudson Valley’s three U.S. House members. Analysts predicted the new map would effectively cut the number of Republicans in the state’s House delegation to just four, down from eight under the map (left) adopted a decade ago. Then a judge declared the new map unconstitutional, leaving the state’s politics in limbo.

By MAURY THOMPSON

Contributing writer

The once-a-decade congressional redistricting process in New York has been a bit like a game of musical chairs locally, with places like northern Rensselaer and Saratoga counties and the city of Glens Falls suddenly finding themselves sitting in what had been neighboring House districts.

From a political standpoint, the new congressional map pushed through in early February by the Legislature’s Democratic majority might not have yielded any major changes in the region.

If anything, the map appeared to improve the re-election chances of local incumbent Reps. Antonio Delgado, D-Rhinebeck, and Elise Stefanik, R-Schuylerville, while the district of Rep. Paul Tonko, D-Amsterdam, was set to turn a slightly lighter shade of blue.

But statewide, most analysts predicted the new map would reduce the number of Republicans in New York’s House delegation for the next five elections to come.

Republicans challenged the map in court, and on March 31, a state judge declared the new map unconstitutional. Democratic leaders vowed to appeal the judge’s ruling, leaving the state’s politics in limbo as April began.

Many nonpartisan observers had joined the state’s Republicans in describing the New York’s new congressional and legislative district maps as a case of gerrymandering -- the manipulation of district lines for unfair partisan advantage.

The online news site Politico said the state’s new maps were the result of “the most aggressive gerrymandering in the country.”

FiveThirtyEight, the website of statistical expert Nate Silver, called the maps “egregiously biased.”

And the Princeton Gerrymandering Project, which provides nonpartisan statistical analysis to support the elimination of gerrymandering, gave New York’s redistricting plan an overall grade of F, the lowest score possible, and said those drawing the maps could “do much better.” In individual categories on its report card, the group gave the New York plan a C for political favoritism, an F for competitiveness, and an F for its geographic features.

“The purpose was to take four Republican House seats out of New York — that’s the bottom line,” said John Faso, a lawyer who has been advising state Republicans on their court challenge. Faso, a Republican who represented Columbia County in the state Assembly for many years, served one term as the 19th Congressional District representative before losing to Delgado in 2018.

New York is losing one House seat as a result of the 2020 census. Republicans currently hold eight of the state’s 27 seats. Under the map passed by the Legislature and signed into law by Gov. Kathy Hochul in February, the GOP was expected to wind up representing just four of the remaining 26 House districts.

Court review pending

In their legal challenge, Republicans argued the plan violates a 2014 amendment to the state constitution, which the GOP claims “prohibits partisan and incumbent-protection gerrymandering.”

Lawyers for the state have argued that the new maps were shaped not by partisan bias but by population trends, the state’s geography and a federal law requiring that racial and language minorities have an opportunity to participate in the electoral process.

The state’s lawyers wrote in a court filing that Republicans’ criticisms of specific new districts “disregard the interconnections between and among districts and regions that naturally constrain the range of available choices.”

The lawyers pointed out that the population in New York City, which is largely Democratic, increased over the past decade, while the population decreased in traditionally Republican areas upstate.

“These population shifts significantly constrain the range of choices available with respect to a new congressional map,” they wrote.

Despite the court challenge, November’s elections had been expected to go forward using the maps already adopted by the Legislature. Candidates are already circulating nominating petitions based on the new district lines.

But then the judge hearing the GOP challenge ruled March 31 that the new maps are unconstitutional. State Supreme Court Justice Patrick McAllister of Steuben County gave the Legislature until April 11 to come up with a new plan that could attract bipartisan support. Failing that, he said the court would appoint its own expert to draw a new set of maps.

Democrats were expected to seek a stay of the judge’s ruling while they pursue an appeal, and the issue could wind up being decided by the state Court of Appeals. If the high court’s judges rule that the Legislature’s plan is constitutional after all, the Democratic-crafted maps might remain in effect.

The legal wrangling could wind up delaying the state’s congressional and legislative primaries, now scheduled for June, until July or August.

Shifting local boundaries

Several analysts have pointed out that, under the maps adopted by the Legislature, districts that previously were competitive were redrawn to give Democrats a voter enrollment advantage, while districts that already had a Democratic advantage retained enough of an edge that incumbent Democrats would be unlikely to lose to a Republican challenger.

In the process, the Democrats who controlled the process redrew district boundaries to shift more Republican voters into districts that were already heavily Republican.

For example, Schoharie County, which has a Republican enrollment advantage, was redrawn from the 19th District, where Delgado is the incumbent, into the revised 21st Congressional District, where Stefanik is the incumbent. Several strongly Republican towns in northern Rensselaer County also were shifted from Delgado’s district into Stefanik’s.

The 19th district was redrawn to include two towns in Albany County and to stretch westward into portions of Broome, Chenango, Madison and Oneida counties, taking in the cities of Binghamton and Utica and thereby adding somewhat to its Democratic tilt.

Rensselaer County previously was mostly in the 19th district, except for the city of Troy and the towns of North Greenbush, East Greenbush and part of Schodack, which were in the Albany-area 20th district represented by Tonko. Under the Legislature’s map, the county is split three ways, with Troy remaining in Tonko’s district while Delgado’s 19th district gains North Greenbush, East Greenbush and all of Schodack while retaining the towns of Berlin, Nassau, Sand Lake and Stephentown.

Tonko’s 20th district also was extended northward from Saratoga Springs to include the towns of Wilton and Moreau as well as the Warren County communities of Glens Falls and Queensbury, all of which had previously been in Stefanik’s 21st district.

In the 19th district, where Delgado is the incumbent, the Legislature’s map doubled the overall Democratic enrollment advantage from 4.2 to 8.4 percentage points. An analysis by Politico concluded that while President Biden carried the old 19th district by 1.5 percentage points in 2020, he would have won the newly configured district by 10.3 percentage points.

The Princeton Gerrymandering Project estimates that, based on voter enrollment and demographic statistics, a generic Democratic candidate could expect to receive 51.72 percent of the vote in the redrawn 19th district, while an unnamed Republican candidate would garner 48.28 percent of the vote.

FiveThirtyEight changed its rating for the 19th district from leans Republican to leans Democratic.

Republican Marcus Molinaro, the Dutchess County executive, is challenging Delgado’s bid for a third term in November.

Preserving partisan advantage

In the 20th district, where Tonko is the incumbent, the Democratic voter enrollment advantage decreased -- from 19 percentage points to 14.2 percentage points – under the map passed by the Legislature. But the revamped district still would lean strongly Democratic: Biden would have carried it by 17.7 percentage points, compared with the 21.1-point edge he rolled up in the old 20th district in 2020, according to the Politico analysis.

The Princeton Gerrymandering Project estimates that statistically, a generic Democratic candidate should receive 53.74 percent of the vote in the redrawn 20th district, while a Republican candidate would earn 46.26 percent. FiveThirtyEight changed its rating for the district from solid Democratic to leans Democratic.

Republican Liz Lemery Joy, a former blogger and speaker from Schenectady, is challenging Tonko as he seeks an eighth term in November.

In the 21st district, where Stefanik is the incumbent, the Republican enrollment advantage increased from 11.5 percentage points to 13.8 percentage points under the Legislature’s plan. Donald Trump would have carried the revamped district by 19.4 percentage points, according to the Politico analysis, compared with his 10.6-point margin in the district as it was previously configured.

The Princeton Gerrymandering Project estimates that statistically, a generic Republican candidate would receive 62.85 percent of the vote while a Democratic candidate would draw 37.15 percent in the redrawn 21st district. FiveThirtyEight changed its ranking of the district from leans Republican to solid Republican.

The state Republican Party’s lawsuit specifically cited the Legislature’s redrawing of the 19th district as an example of gerrymandering.

In court papers, the GOP claimed the revised district “is significantly drawn for the impermissible purpose of strengthening the Democratic Party’s political interests, with the far-reaching corners of Congressional District 19 showing how the Legislature shopped for Democratic voters in order to turn the district from Republican-leaning to a Democratic-advantage district.”

Lawyers for the state responded that the old 19th district was one of the three most underpopulated districts in the state, and that geographic changes were made to account for the net loss of one district in New York.

“District 19 represents a similar shape to its predecessor,” the state contended.

The Republican lawsuit also cited the 21st district, saying the Legislature reshaped it “to pack it with additional Republican voters.”

Lawyers for the state responded, however, that population in the district had to be increased by 71,930 people to meet a federal rule as the state lost one seat overall, so the map makers expanded the district to encompass similar rural areas.

Deadlocked reform effort

The outcome of New York’s redistricting is not what public interest groups had hoped for when voters approved a constitutional amendment in 2014 that led to the creation of the state’s Independent Redistricting Commission.

A coalition of reform groups had pushed unsuccessfully for the state to create an independent body to draw the state’s political maps. Their goal was to foster a more open and transparent map-making process that would be insulated from partisanship.

Instead, then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo and legislative leaders proposed a commission whose members were appointed by the state’s political leaders. That plan, which also gave the Legislature the right to reject the independent commission’s proposals, won voter approval in 2014.

The commission, which started work last year based on the results of the 2020 census, ended up submitting separate sets of maps to the Legislature -- one drawn by the panel’s Democratic members and the other by its Republicans. With the commission unable to agree on a consensus plan, the Legislature took over control of drawing the maps.

In addition to its argument that the maps are the result of gerrymandering, the Republican lawsuit contends the Legislature was not authorized to draw the maps because the Independent Redistricting Commission never formally submitted a second set of maps to the Legislature.

The 2014 law that established the commission requires the Legislature to reject two consecutive commission plans before taking charge of the redistricting process.

Lawyers for the state contend the Legislature’s redistricting process followed the law.

Blair Horner, executive director of the New York Public Interest Research Group, has said that before the next redistricting in 10 years, the state should overhaul its process by creating a commission that operates with total independence from the Legislature.