News & Issues February-March 2022

Wages of change

In New York’s new overtime rules, some see agriculture’s transformation — or its ruin

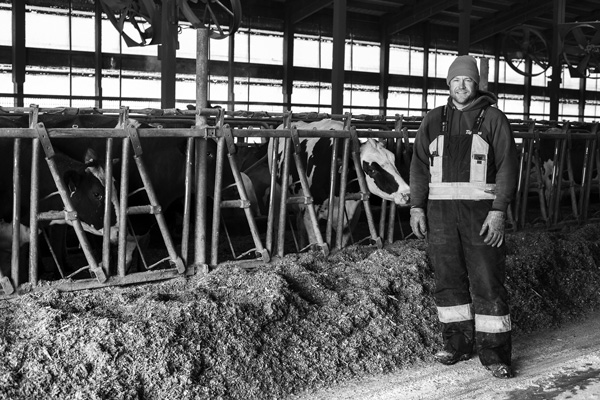

Stewart Ziehm tends to the cows at Tiashoke Farms, a dairy operation near Buskirk, N.Y., on a cold winter day. Joan K. Lentini photo

By EVAN LAWRENCE

Contributing writer

CAMBRIDGE, N.Y.

Labor and social justice activists are calling it a huge step forward for the lives of farm workers in New York.

But many farmers and their advocates say they fear the change could deliver a mortal blow to agricultural businesses across the state.

On Jan. 28, the state’s Farm Laborer Wage Board voted to lower the weekly threshold at which farm laborers become eligible for overtime pay to 40 hours — the same standard that’s applied to hourly workers in nearly every other economic sector for decades.

If the state labor commissioner signs off on the board’s plan, the change from the current overtime threshold of 60 hours per week for farm workers would take place in a series of increments over the next decade. The first step, effective in two years, would require overtime pay after 56 hours of work.

Farmers who’ve opposed the change say the unique pressures of agriculture — including perishable crops, the threats posed by severe weather and the demands of caring for livestock — deserve a more flexible standard.

In addition, after struggling for years to recruit and retain agricultural workers, many farmers in the region have come to rely increasingly on foreign laborers who live at the farm and want to log as many hours as possible. Now farmers fear they could lose those workers if they have to cap their weekly hours to hold down labor costs.

Stuart Ziehm, a partner at Tiashoke Farms near the hamlet of Buskirk, said a 40-hour overtime threshold “would be extremely challenging.” The 1,000-cow family dairy farm has 24 hired staff, half of them from the local area and half from Guatemala.

“Labor is the second largest cost on a dairy farm, after feed for the cows,” Ziehm said in an interview before the wage board’s decision.

If the state switches to a 40-hour threshold for overtime, the farm would lose what’s now a very small margin of profit, he said. Workers who are eager to work 55 to 65 hours a week would go to other states where there’s no limit on their hours, he predicted, and the farm would be unable to invest in itself and its community.

“We’d lose the ability to evolve,” Ziehm said. “Banks don’t want to invest in businesses that can’t be profitable.”

But labor leaders and worker advocates who pushed for the change say farm workers should be treated the same as everyone else.

“The bottom line is: This is a matter of equality,” said Emma Kreyche, director of advocacy outreach and education at the Worker Justice Center of New York. “In 2022, we still have second-class workers.”

Stewart Ziehm of Tiashoke Farms says some of the 1,000-cow dairy operation’s 24 employees would leave if he has to curb their hours because of New York’s new overtime pay rules, but having to pay them all a time-and-a-half rate after 40 hours could wipe out the farm’s profit margin. Joan K. Lentini photo

Decades-old exemption

The federal Fair Labor Standards Act established the right to time-and-a-half pay after 40 hours per week for most U.S. workers in 1938. Left out were farm and domestic workers, who in the South were primarily African-American. Southern senators refused to support the bill unless it excluded those groups; they wanted to keep Black workers from parity with white workers.

Three years ago, New York redressed some of that exclusion by passing the Farm Laborers Fair Labor Practices Act. The new state law, which took effect at the beginning of 2020, gave farm workers the right, among other things, to one day of rest per week, the right to organize, unemployment insurance — and overtime pay after 60 hours per week.

The law also directed the state Department of Labor to set up the Farm Laborer Wage Board, which was tasked with determining whether the overtime threshold should be lowered to 40 hours or some intermediate number.

Four other states — California, Hawaii, Maryland and Minnesota — require overtime pay for farm workers, with thresholds ranging from 40 to 60 hours.

In New York, the new wage board began holding hearings on the issue in February 2020, but the process was interrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic. The board was supposed to issue a recommendation in December but instead scheduled three more virtual hearings in January.

All three hearings ran for more than three hours, and a fourth was added on Jan. 28 to accommodate dozens of people who hadn’t yet been able to speak. After the conclusion of that hearing, the board voted 2-1 to lower the overtime threshold in a series of steps, reaching 40 hours by 2032.

Farming’s special needs

Only 27 percent of New York’s farms have hired labor, but those farms account for 90 percent of the state’s net farm income, according to state statistics. All but 2 percent of the state’s farms are family owned.

Farmers say they have special needs when it comes to labor. Harvest windows for fruit and vegetables may be measured in hours, especially if bad weather is coming. The few weeks of harvest may bring in almost all the farm’s profit for the year.

Farm emergencies — storms, equipment breakdowns, livestock in distress — can happen at any time. In these situations, work must continue until the job is done, no matter how matter long it takes. Farm families take it for granted that, when needed, they might have to put in 80 hours or more of work in a week.

And in contrast to many other businesses, farmers say they are often unable to pass higher costs on to customers. In the case of dairy farmers, the price they’re paid for milk is set by complex federal regulations.

“We’re paid at just above or just below the cost of production,” Ziehm said.

Making more milk isn’t a solution, as nearly all dairy farms sell to processing cooperatives that will only buy a set amount.

“The co-ops don’t allow overproduction,” Ziehm said. “They’re flush with milk.”

For produce growers, labor typically is the biggest expense. Dale-Ila Riggs, co-owner of The Berry Patch in Stephentown, told the labor board she can’t possibly match the prices of the California berries sold at her local big-box supermarket. Riggs said she got rid of her raspberries, plowed under her strawberries and lost 40 percent of her blueberries to rot last summer because she couldn’t afford the labor needed to pick them.

Many farmers say their ability to pay workers is constrained by market prices for their products – prices that in many cases have been in decline.

Sarah Dressel Nikles, a fruit grower in New Paltz and member of the New York Apple Association board, said that if she received the equivalent in today’s dollars of the $3.75 per box her grandfather received in 1953, she’d be getting $37.22 for a box of apples. Instead, her average price last year was $18.

A baby cow is part of the next generation of milk producers at Tiashoke Farms in the town of Cambridge. Joan K. Lentini photo

At the board’s hearings, farmers also stressed that many of their workers want to log as many hours as possible and don’t want to lose out because of a state limit.

Ziehm said about half of Tiashoke Farms’ workers want to work 55 to 65 hours per week.

“They sacrifice a lot to be here, and they’re motivated by grabbing as many hours as they safely can,” he explained.

The farm’s other workers tend to log 50 to 55 hours a week, except at harvest time, he said.

“Of course all workers would appreciate overtime,” Ziehm said. “But they appreciate that we need to be sustainable and profitable.”

Farms with hired labor often provide no-cost housing for their employees. For foreign workers hired through the federal H-2A program, employer-provided housing is required. Farms may also arrange for workers’ transportation and provide some food.

Would workers leave?

In a state-commissioned report released in November, Cornell University researchers interviewed H-2A workers about pay thresholds. Of those interviewed, 72 percent said they would be less likely to take a job with a 40-hour overtime threshold if it meant that they would receive no more than 40 hours a week of work, and 70 percent said they’d go to another state with no cap on their hours.

But Kreyche, at the Worker Justice Center, said talk of limiting workers’ hours because of the overtime threshold is something of a misrepresentation.

“The state isn’t limiting how many hours workers can be assigned,” Kreyche said, although she added that employers might be giving their workers that impression. “It’s saying that employers have to pay overtime after 60.”

Kreyche said she couldn’t speak for all farm workers, who come from many backgrounds, are working in different situations, and have different goals. But last year, her organization’s staff talked to about 2,500 workers at more than 250 farm worker housing sites around the state, and “this is what I’ve seen,” she said.

Kreyche questioned whether H-2A workers, most of whom are coming from the Caribbean and Central America, would really go to other states if New York lowered the overtime threshold.

“H-2A workers may only be here for six to eight weeks, and they want to earn as much as possible in that time,” she said. “But they’re a small minority of the state’s total agricultural workers,” who are estimated to number 55,000 to 60,000.

“There won’t be a shortage of H-2A workers,” Kreyche said. “The workers know that … there are a dozen people behind them in their home countries waiting to come. The growers are relying more and more on that work force.”

Under the program’s rules, workers are required to stay with the employer who brought them to the United States.

“They can’t shop around” for a better job, she said.

There’s also the question of where workers would go if they bypassed New York. H-2A workers’ minimum wages are based on the minimum wage in each state. New York has one of the highest minimum wages in the country, at $13.20 this year for upstate, and it will eventually increase to $15. Only California ($14), Washington state ($13.69), and Massachusetts ($13.50) are higher, according to an October report from Farm Credit East, and California already requires overtime after 45 hours.

In contrast, Vermont’s minimum wage is $11.75, and Pennsylvania follows the federal minimum of $7.25. Agricultural workers in New York may have fewer hours if employers choose not to assign overtime, but they’d still be ahead of workers in many other states.

“New York’s pay is a pretty big incentive for retention,” Kreyche said.

Dairy farms’ long hours

The situation for dairy farm workers is different, Kreyche said. Big dairy farms run 24 hours a day, seven days a week, year-round.

“This is where we see workers with the longest hours and most hazardous conditions with the least regulation,” she said.

Before the state’s 2019 law established a mandatory weekly day of rest, it wasn’t uncommon for dairy laborers to work seven days a week for weeks on end, she said.

“We see 12-hour shifts, six days a week, in dairy,” Kreyche said. “The pay differential in overtime after 60 hours versus overtime after 40 is significant.”

Unlike H-2A workers, who are mostly single men, many dairy farm workers have their families with them.

“They may be earning $50,000 a year, but they’re working 72 hours a week,” Kreyche said. “That’s not a life.”

Historically one of the justifications for overtime pay was to discourage employers from overworking their employees, and worker safety was a key factor cited by supporters when the benefit was extended to New York farm workers two years ago. Farming overall ranks in the top 10 of most dangerous occupations, and dairy farming is particularly hazardous.

“People who work this hard labor are much more likely to be injured,” Kreyche said.

Workers may push themselves to the point of physical disability but often don’t have access to health care, especially if they’re undocumented.

“No one wants to work 60, 70, 80 hours of difficult manual labor without overtime,” Kreyche said.

Ziehm acknowledged that safety becomes a concern for those working particularly long hours.

“Eighty-hour work weeks aren’t a great idea,” he said. “We’re very well aware of the safety risks with extended hours.”

Tiashoke Farms works with a state program for agricultural health and medicine for safety training, he said.

Kreyche said finding dairy farm workers is challenging because there’s no federal guest worker program for year-round agricultural operations.

But David Kallich of the Immigrant Research Institute, who spoke at the Jan. 20 hearing, said higher pay should help to increase the pool of available workers.

“Better wages don’t lead to fewer job applications,” Kallich said.

Worker advocates point out that other industries have been able to adapt to 40-hour overtime thresholds, including in highly seasonal businesses such as resorts, landscaping and construction – and at those that run around the clock, such as health care.

“The industry will have to change,” Kreyche said. “Agriculture is no different.”

But farmers insist their ability to change is limited. They can adjust workers’ schedules and possibly invest in labor-saving equipment, but not all farms have the resources or the set-up to make that feasible.

In addition to Covid-related disruptions and rising supply and equipment prices, farmers are dealing with a state minimum wage that has increased by about 70 cents an hour annually since 2013. Those wage increases have been accompanied by higher payroll taxes and other wage-based costs.

New York farm workers on average earn about $4 an hour more than the state minimum wage, according to state statistics.

“In business, you can invest in labor or you can invest in large machinery to cut down on hours,” Ziehm said. “Every situation is different. You still need team members to make sure the farm runs smoothly.”

An exodus of farmers?

The Farm Credit East report noted that given the tight U.S. job market, many farmers doubt they could readily find more workers, and farmers who provide housing may not be able to build more. The report concluded that with a 40-hour overtime threshold, dairy farms would lose their entire profit margin, and fruit and vegetable producers would lose 73 percent of their profits.

The Cornell report predicted equally dire results. In interviews with Cornell’s researchers, two-thirds of dairy farmers said they’d get out of dairy farming, invest out of state, or leave agriculture altogether. Half of fruit and vegetable farmers said they’d shrink their operations or exit production.

The results weren’t quite as bad with a 50-hour threshold, but the report noted that farmers have already adopted the easy fixes, such as contracting out some labor-intensive operations or cutting back or eliminating the more demanding crops.

“If we were to move from 60 to 55, that would be more manageable, but not easy,” Ziehm said. “That’s much more realistic than a move to 40.”

On the other hand, advocates of lowering the threshold cite state statistics showing since the 60-hour overtime requirement took effect, both the number of farms in the state and their gross cash income have gone up.

The Farm Bureau of New York, allied agricultural organizations, and individual businesses formed a coalition, Grow NY Farms, to push for keeping the threshold at 60 hours. Many of the coalition’s members testified before the Farm Labor Wage Board, where comments were heavily opposed to any changes in the threshold.

Although labor and social justice activists also testified, few farm workers took part in the first three hearings. Kreyche said access to the online hearings was difficult for farm laborers, but she expected more would submit recorded testimony for the Jan. 28 hearing.

Area legislators oppose change

Most state legislators in the region were on record in opposition to lowering the overtime threshold.

Assemblywoman Carrie Woerner, D-Round Lake, has many dairy and some fruit and vegetable farms in her district, which covers parts of Saratoga and Washington counties. In a statement issued in September, she called the current 60-hour threshold a compromise.

“As agricultural work is seasonal, many farm workers still seek to work as many hours as possible when the work is available,” Woerner wrote. “A further reduction of the overtime threshold will reduce their already limited opportunity to work. Moreover, any reduction threatens farmers’ ability to afford workers during the peak season and consequently the ability to operate these farms at all.”

The state needs to maintain a reliable local food system to reduce its dependence on imported food, Woerner said.

Assemblyman Jake Ashby, R-Castleton, whose district includes parts of Rensselaer, Columbia and Washington counties, has held two summits with farmers in his district, said Tom Grand, Ashby’s chief of staff. Participating farms ranged in size from those with two employees to those with a hundred, Grand said.

The consensus was that a 40-hour overtime threshold would “not only be bad for farmers and businesses, it would be bad for workers because it would lower their hours,” Grand said. “It doesn’t help either side.”

State Sens. Daphne Jordan, R-Halfmoon, and Dan Stec, R-Queensbury, were among 13 Republican state senators who signed a letter to the members of the Farm Laborer Wage Board asking them to delay action on the overtime threshold until the end of 2024. They cited the Cornell study and said the board needs more time to review the effects of the 2019 law.

In her budged address for 2022-23, Gov. Kathy Hochul proposed new tax credits for farmers to offset added overtime expenses, although the details of those proposals have yet to be worked out. Hochul also supports an increase in investment tax credits, and an extension and doubling of the Farm Workforce Retention Credit, which currently provides farmers with a tax credit of $600 per employee per year.

The Farm Bureau specifically supports the workforce retention credit and generally backs other budget proposals intended to benefit farmers, although critics note that tax credits require farmers to lay out money first and be reimbursed later — and that state budgets are subject to annual negotiations that make such benefits unpredictable.

Kreyche, of the Worker Justice Center, said she also supports providing tax credits or other benefits to help farmers meet the new overtime pay requirements.

“I would fully support any subsidies or incentives to create a better future for farm workers,” Kreyche said. “It would help us all collectively to absorb these costs.”