Arts & Culture February-March 2022

An artist who changed views of printmaking

Show at Hyde celebrates master printer Blackburn and those he inspired

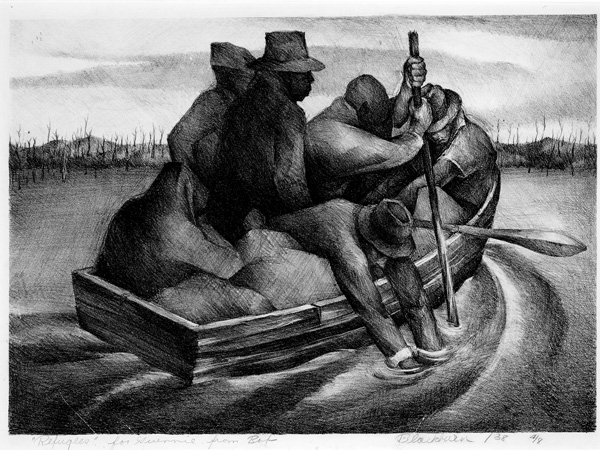

Robert Blackburn’s “Refugees” (also known as “People in a Boat”) was completed about 1938, when he was still a teenager, and nearly a decade before he opened the printmaking workshop that would reshape his own art and the works of many others. He discovered lithography in his early teens through programs at the Harlem Community Art Center. Collection of NCCU Art Museum, North Carolina Central University

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

GLENS FALLS, N.Y.

On a winter night, a man in a wool sweater, knitted hat and glasses applies ink in a film of color.

He is adapting easily to its thickened texture in the cold. Artists and printmakers are standing around a limestone block, and sheets of paper are hung carefully on the walls and spread out to dry.

In an etching, a collage of boys’ faces overlies beams and bolts and a tunnel arch. The background is highlighted in red and yellow, rubbed like old paint on cement.

In a lithograph, two women are holding each other as though they’re dancing, lean and muscled in loose orange and saffron dresses. Light on their dark skin seems to show the strength in their arms. One looks out wearing sunglasses.

In 1947, on West 17th Street in New York, Robert Blackburn founded the oldest artist-operated and directed printmaking workshop in the country, in the words of Cherokee artist Kay Walkingstick, who introduced a Blackburn exhibit at the Bronx River Arts Center and the Hillwood Art Museum in 1992.

Blackburn’s workshop was an open and experimental place, where he could grow his own art — and a community of artists in New York City and around the world.

It was an upstairs loft where young painters could find equipment they otherwise wouldn’t have access to. A nationally known artist like Romare Bearden might spend a Saturday there, working on an etching like “The Train.” South African filmmaker Dumile Feni, who had created a monumental 40-foot work at the United Nations and represented his country at the Sao Paolo Bienniale, pulled prints for “Dedication, Ruth First, Lilian Ngoyi.”

In that congenial room, Blackburn developed lithography and printing as an art form, said Jonathan Canning, curator at The Hyde Collection in Glens Falls. Blackburn ran the workshop for nearly 60 years in his lifetime, and he made sure it is still running nearly 20 years after his death.

Now the Hyde is welcoming his work and his story in “Robert Blackburn and Modern American Printmaking.” The exhibition, curated by Deborah Cullen-Morales and organized by the Smithsonian, opened Jan. 29 and runs through April 24.

“He’s an artist in his own right,” Canning said, “He’s very influential as a teacher and organizer of a printmaking studio in which he works alongside and brings on artists.”

Some of those artists are very well known, he added. And they might not have worked in the print medium without Blackburn’s influence — and without the workshop he started when he was 27.

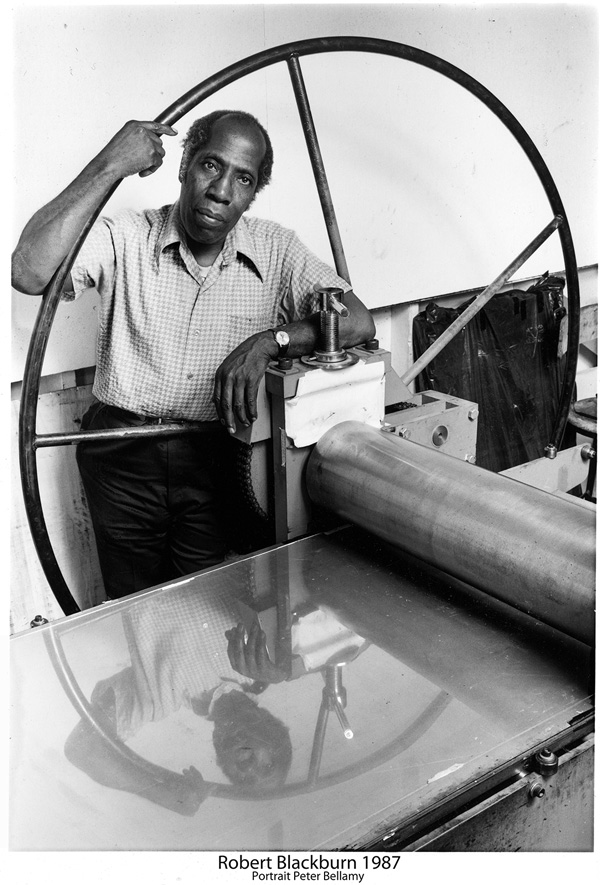

The artist Robert Blackburn is seen in 1987, 40 years after he founded what became the oldest artist-run printmaking workshop in the nation. The workshop still operates nearly two decades after his death in 2003. Peter Sumner Walton Bellamy photo, courtesy Smithsonian Institution and The Hyde Collection

A revolution in print

Lithograthy begins with a smooth limestone block. Draw with grease crayons or a thick dark liquid, dampen the surface and then roll printer’s ink over the stone. The ink will only stick to the greasy surface. Set damp paper on top and run it through a press, and the ink will print to the paper.

Blackburn first discovered lithography through programs at the Harlem Community Arts Center.

“Romare Bearden would drop by … and Richard Wright … Jake Lawrence, Sarah Morell, Norman Lewis used to come up and have rap sessions. As a matter of fact, it was a real center of the visual arts,” he recalled in a 1972 conversation with artist Camille Billops and Jim Hatch that is preserved on the website of the Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop.

In the 1930s, at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, the community arts center drew artists, writers and dancers working with the Works Progress Administration, the Depression-era infrastructure agency. Blackburn was 13 when he first came there, he said, and he was the youngest. He knew one or two young teens there, and he mixed with artists and writers like sculptor Selma Burke and Langston Hughes and Claude McKay.

“He was in high school when he was meeting these WPA artists,” Canning said. “And I think one of the earliest works in the exhibition, he’s about 19, and that’s just extraordinary.”

As the Depression and World War II shook the country, Blackburn took art classes after school and work and won a scholarship to study at the Arts Students League. His early prints show the influences of Mexican muralists like Diego Rivera, and of social realism, Canning said.

Blackburn imagined clear scenes, showing people involved in physical energy and hard moments in their lives. In “Refugees (aka People in a Boat),” created about 1938, people hold close together in a wooden dinghy low in the water. Blackburn’s parents had met on a boat coming from Jamaica.

By the time he opened the print shop in 1947, he was moving into still lifes with exaggerated or shortened surfaces, broad strokes and vivid color.

“We see him move away from representation and the sort of social commentary images he depicts in some of his earlier prints — laborers, the unavailability of work, daily life,” Canning explained. “Then he moves into abstraction, … color and form and space.”

But even when his work could seem to offer less commentary on daily lived experience, Blackburn was working with artists who were very much exploring contemporary themes, Canning said.

“In 1974, the workshop produces a series called ‘Impressions of Our World,’ and Blackburn contributes imagery there,” he said.

Blackburn was holding those conversations as he was pushing the boundaries and technical abilities of the print process.

“We see him growing as an artist,” Canning said. “He was a highly skilled lithographer. … He starts trying different print techniques.”

Blackburn’s creativity powered him “through a long career and an incredible span there, from the 1930s and the Harlem Renaissance right through the Black Power Movement,” he added.

Along with generations of lithographs, the show includes his experiments in watercolors and woodcuts, viscosity intaglios, monoprints and etchings.

In his 1950 print “Girl in Red,” a woman stands with her back to a window, looking clearly into the room. She is comfortable and confident, at the center in her own space. He invokes her in abstract broad planes of color, and the sunlight warms her forehead and her shoulder.

Founding a workshop

It can be a challenge for an artist to find the time and space needed to sustain their work. And in the early 1940s, Canning said, Blackburn was working full time.

For a few years out of school, Blackburn held odd jobs and had no access to a press. And in the 1940s, there were few grant programs to which Black artists could apply, explained Cullen, the show’s curator, in a talk at El Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Havana organized by The Bronx Museum of the Arts. (Cullen also spoke virtually as the local show opened Jan. 28 at the Hyde.)

So Blackburn made his own way. By late October 1947, he got his own press and moved into the loft of West 17th Street with four other artists.

“That’s the traditional artists area,” Canning said. “That’s where John Slade had his workshop and his studio in the ’20s and ’30s.”

Cullen said Blackburn continued working to support his art.

“After work, he would work from 5 pm. to 2 a.m. on his own litho press,” Cullen said. “Over time, the others moved out and he kept the space.”

She shared a memory from Tom Laidman, one of the founding members of the workshop, who worked with Blackburn until his death in 2003.

“When I came there in 1950, the shop was on West 17th Street in a four-story red brick building,” Laidman recalled. “There was no elevator, and everything in the place went up on our backs, including the presses, stones, lumber for building, coal for the stove in the middle of the shop.

“We froze in the winter, roasted in the heat in summer, and the heat didn’t make the printing any easier. We went through all kinds of maneuvers to keep the images in the stones from filling in.”

Blackburn welcomed in artists, friends, and friends of friends. The community grew until it became an informal cooperative and then, in 1971, a nonprofit.

“The structure of it changes over time,” Canning said.

“The atmosphere was friendly and intimate,” Laidman recalled. “There was an open arrangement where … students and artists had unlimited access. There were three or four litho presses, and we’d all fight for press time. Bob was a dynamo of energy.”

Powering a community

Cullen knew that energy herself. As an intern for Blackburn, she worked with him at his workshop, and later she served as curator of the print collection at the nonprofit he helped to form to keep the workshop alive past his own lifetime.

Not many collective spaces existed in the 1940s, Canning said. It was rare for artists to have a place like this, where they could come together. They could find the tools and inks they needed and work with printers who knew what the tools could do. They could learn and teach — and talk with each other.

“There must be so much sharing and discussion going on between artists,” Canning said. “It becomes such an influential place for ultimately an international crew of artists to work, to share ideas and to experiment in different print techniques and media.”

Blackburn taught other artists, and he worked with artists as teachers. The Indian artist Krishna Reddy, a master printmaker and voice for abstract art in India, led workshops in viscosity — etching a metal plate at different depths and then printing with inks of different thicknesses. In the 1970s, when he was creating the etching in this show, Reddy was a professor at New York University.

Here he shows four boys — or are they the same boy in different times and places? — sitting on what might be sand at the tideline, in a space that feels limitless and divided into invisible rooms, with a sky like water or the grain of wood.

Blackburn made two prints in this show the same way, and he learned from many of his friends. From 1974 to 1983, Romare Bearden taught monoprinting at the workshop and worked with Blackburn on his own monotypes. Together they made more than 100 prints, often on Saturdays.

Blackburn himself taught in New York and across the country. Alongside his workshop, he served for years as professor to the printmaking workshop at the Cooper Union and taught at Columbia University and the Pratt Institute, and he held lectureships across the country, from Rutgers to the University of California at Santa Cruz, according to the catalog to “Through a Master Printer: Robert Blackburn and the Printmaking Workshop,” an exhibit at the Columbia Museum in 1985.

“Blackburn welcomed many Caribbean and Latino artists,” Cullen said in her Havana talk, “and many Puerto Rican artists worked in his shop, including Nestor Otero, Juan Sánchez, Nitza Tufino.”

Cuban artists came there too, she said, including Eduardo Roca ‘Choca’ Salazar, who had earned international recognition and shown his work from Bulgaria to Galicia to the International Engraving Triennial Exhibition in Japan.

As Blackburn’s influence spread, over the years the artists who came through his workshop would form their own communities. The result was that Blackburn inspired new print shops in many places. In 1978, he traveled to Asilah in Morocco to found a print workshop there.

“It’s interesting to think how international modern art was,” Canning said, marveling. “The idea of setting up an international print workshop in Morocco in the 1970s seems extraordinary.”

Changing ideas

From his workshop in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan, Blackburn was influencing the way artists across the country were thinking about printmaking, Canning said. He became a leader and a catalyst in a national movement toward prints in the 1960s and ‘70s.

For Blackburn, printing was an art form in itself -- tangible, messy, changeable and organic. He made lithography and many forms of printing possible, and in introducing them to well-known artists, he made them newly legitimate, Canning said.

Lithography had become a technique for illustrating books. Artists more often worked with woodcuts, etching and engraving. Blackburn showed them that they could use lithography for their own ends and take it back from commercial presses and newsrooms.

Many artists have turned to printmaking for freedom in the way the work is made and put out into the world, Canning said, just as Japanese woodblock prints (shown at the Hyde in 2018, and showing this winter at the Southern Vermont Arts Center and Williams College Museum of Art) gave artists a way to show their work and gave many people a way to see it.

Artists would come to Blackburn thinking of lithography as a way to make a perfect copy of an image, a drawing or a painting, Cullen said. He knew lithography as a creative process and a way to experiment. And he shared his knowledge widely.

From 1957 to 1963, Blackburn worked as master printer for another new print shop, Universal Limited Art Editions on Long Island, and there he met some of the most widely recognized artists of the time. In those five years, he printed ULAE’s first 79 editions, including work for Helen Frankenthaler, Grace Hardigan, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg and Larry Rivers. Many of them had never worked in print until they met him.

Blackburn had been “thinking in print for more than 20 years,” Cullen explained. His experience influenced these artists when they began working with the stone, and he taught them what was possible.

“He defied the idea of lithography as faithfully reproducing a rigidly identical print edition,” she said.

And he turned perspective on its side: An easel is a vertical surface; a press, a stone, is horizontal.

In one powerful moment, Rauschenberg and Blackburn were working together when the stone cracked -- and Rauschenberg put the fragmented prints together, and made them something new.

“I hope this show will be a real eye-opener for us,” Canning said, “and it will open our understanding of 20th century art.”

The show is introducing Blackburn and the Hyde to many artists new to them, he said. Looking ahead to the museum’s summer exhibit on the Mexican artist Jose Guadalupe Posada, Canning said he thinks of the Mexican muralists like Diego Rivera who inspired Blackburn as a boy. As he sees the prints for this show for the first time, he imagines new connections they can make in the future.

“I think this show could seed a lot of future exhibitions,” he said.