Arts & Culture April 2022

Culture and history, distilled into objects

Ceramics, sculpture anchor new shows at Mass MoCA

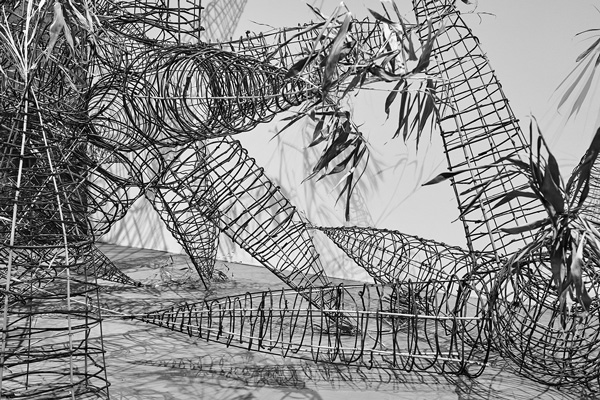

Tomato frames bound together with kudzu vines form one portion of Lily Cox-Richard’s new installation, “Weep Holes,” at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art in North Adams. The museum also has a new group show, “Ceramics in the Expanded Field,” with works by eight artists. Photo coursey of Mass MoCA

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

NORTH ADAMS, Mass

Last summer in southern California, a group of friends made clay bowls in their back yard.

They shaped and smoothed clay into cups small enough to hold one-handed and set them out to dry, and two days later they hardened them in a wood fire in the yard and sat around it. The clay took on a patina from the smoke.

The clay came from the Berkshires, from Sheffield Pottery. And now one of the cups is here, in a room with worn brick walls and afternoon sunlight at Mass MoCA. It’s a mezcal cup, says sculptor and installation artist Armando Guadalupe Cortes. It’s made for a liquor people have distilled from agave for hundreds of years in Mexico, near the town where he was born.

In the Berkshires on the same summer nights, friends were sitting around a hand-thrown earthenware fire pit. They were together outside in a pandemic summer, in a break in the rain, looking for warmth in a brazier the size of a soup kettle. And now it’s here too.

Lily Cox-Richard made these ceramic fire pits and gave them out to people in the community. She asked people to use them, gather around them, and then she brought them together again in “Weep Holes,” one of three new shows that opened at Mass MoCA in March, curated by Denise Markonish.

In her work, like Cortes, Cox-Richard is weaving together questions of care and responsibility for the land, for community, culture and people.

“How do we get to the future,” Markonish asks in the exhibition, “and do so while taking care of one another — how do we mend the damage that is already done?”

Clay, fire and human traditions

Cortes’ cobalt blue mezcal cup sits in a niche on an adobe pillar. He has made an adobe arcade in a framework of cedar, and its ledges hold flints, fire opals, seed pods of datura, brilliant red seeds of Texas mountain laurel — a wide array, many with roots in Urequio, Mexico, the small farming town where he was born.

He lives and works in southern California, and he often returns home to see his family.

In his installation, “Castillos,” he brings tangible ties to the people and the land in a group show of new works by eight artists, “Ceramics in the Expanded Field,” curated by Susan Cross.

Cortes draws together art and crafts traditions going back hundreds of years — traditions that are contemporary and evolving. Work by ceramic artists near Urequio sits here near his own.

“Whenever it’s made, it’s original,” he said. “They’re the same hands, over distance, over time, and it’s the same clay.”

A disc with a pitted surface gleams like lava veined in gold. He made it a few years ago, while he was working as an exhibition manager at UCLA and had the use of the university’s ceramics lab.

Discs echo through the show, he said, invoking the place markers or stelae found at many Mesoamerican archaeological sites, each one a monument to a specific place or township, a city or a ruler.

Nearby a similar form has repeated in his work over the years. A circle of alabaster shows the even ridges of a grinding stone. Five years ago, he said, he was visiting home with his father, and a cousin showed him old lamps, ploughs, farming equipment, things his family has used — a fragment of the door from their great-grandparents’ house, where his grandfather was born.

She showed him a grinding stone made from basalt, with straight lines chiseled in the illusion of a spiral.

He was taken with how beautiful it was, he said. It came from an old mill in town. They have a new mill now with a steel grinder for processing corn. He doesn’t think anyone there still grinds corn by hand in a metate, a stone for preparing corn by hand.

And he thought: That old millstone made food possible for the whole town, 600 people. He felt not just the weight of it but its purpose and service.

That sense of work and strength and care echoes, alongside “Castillos,” in a short film Cortes made in 2017, “El Descanso en la Gloria.” The name translates to “rest when you’re dead.” He had said that half-jokingly to his mother, when he was working full time and keeping up his studio practice on top of it, into the small hours. His mother told him he sounded like an old woman of the village whose name was Enecleta.

The story goes back to a time when Urequio was building a church. The town has many springs, he said, but back then it had no indoor running water. Enecleta would carry water in clay vessels uphill from the river to the work crews. She was a tough elder lady, he said, and she would keep on as long as the builders were working.

“It became a joke between my mother and me about being devoted,” he said.

Enecleta was as committed to the church as he is to making his work and putting it out into the world — and more than that. In all of these seeds and cups, whistles and stones, he is recognizing loss and looking toward a different kind of future.

In “Castillos,” he is keeping stories and histories alive and waiting. A clay whistle or an amulet hold the stories of people who live in Urequio and the towns around it, their art and crafts, cultures and languages, knowledge of plants and animals — and what they have lost in centuries of colonial imposition. Their tools are gathered here.

“They are not on display,” he said, “but in wait.”

They are ready for use, the way his family will keep something conveniently where they last used it, sheers near the fruit trees in the back yard, a rake leaning on one tree and a fruit-picker against another, safe until someone comes to pick them up again.

Recycling into sculpture

In her new installation, Cox-Richard has balanced care for the natural world and care for the people in it. Ceramic fire pots slope against the brick wall, imprinted with patterns of leaves.

In her work, Markonish finds an “immediate shared curiosity for the world.”

“I wanted people who would connect to one another and support each other in that weird process that making an exhibition is,” Markonish explained, “and I think … the volleying back and forth of utter seriousness and utter absurdity.”

She sets Cox-Richard’s “Weep Holes” alongside Marc Swanson’s “Memorial to Ice at the Dead Deer Disco,” as he explores his love of the woods and the nightclubs where he danced and found community as a young man — and the losses flowing from climate change and the AIDS crisis.

Cox-Richard said she creates her work in Tsenacomoco territory, in Richmond, Va., on land that has been inhabited and cared for by the Pamunkey, Monacan, Chickahominy and many other nations for thousands of years. But she and Markonish first met five years ago, when Cox-Richard was living and working in Texas.

They began talking about this show in early 2017, just after the 2016 election, she said, and they originally planned it to open in 2021 (before Covid delayed it). And Cox-Richard too was looking toward a different future.

“I thought, ‘We’ll have a new president by then,’” she said. “Because it was all feeling very fresh. But it was hard to imagine what that would look like or what would happen between now and then. It seems hilarious to think back on that. We had no idea what we were in for.”

Planning this show across five years, she had to adapt and adapt again, she said, to find the through line of the work. As politics, conflicts, climate change and the pandemic have brought challenges she could never have predicted, some elements of the show have strengthened while others have fallen away, and what felt more relevant felt most right.

“It’s longest lead-time I’ve ever had,” Cox-Richard said, “and it felt like the context of the world was shifting constantly in that moment. I was thinking about value, and how we reckon with value and the value … of people’s lives. It felt like that context was changing daily.”

Across five years, some elements of the show have taken on new meanings.

“Sandbags have a new resonance,” she said, “after seeing images and monuments of cultural importance in the Ukraine protected by sandbags. I was thinking before more about other kinds of front lines, but also climate change, trying to keep [out] flood water.”

She is finding new uses for materials that have outlived their first use. A fire hose, now too worn to carry that weight of water, weaves around a row of pillars like basket splints.

And she is playing with abundant organic resources. Kudzu vines bind wooden tomato frames together into tall, slender stars.

“What has stayed has continued to feel important,” Cox-Richard said, “stewardship, cleaning up the mess on the other side of something … and ways to create or maintain connection with people when there’s a need for isolation that neither of us had imagined in the beginning of this.”

She named the show “Weep Holes” for the architectural openings that let water travel freely through a building or a wall. It felt like a beautiful analogy for the way that energy moves through the world, she said, creating resistance and giving freedom.

Fire hydrant as altar

One element in Cox-Richard’s show has become a community gathering point on its own. Around the corner from what looks like the farthest room, at the top of a fire exit, a fire hydrant from North Adams, given by the city, stands decked in beads and yellow roses, with a wreath of bright yellow chrysanthemums at its feet, like a family offering to loved ones for dia de los muertos.

“In the final days of install,” Cox-Richard said, “it became a kind of altar for me in making the final parts of the show, and a place of ritual. And then it has accumulated several offerings since I left. … A cigarette appeared next to it, and some new stones, … so I know other people have made offerings there.”

She thinks of it as a witness, she said. The story goes back to Richmond in the summer of uprisings. She saw a wig on a fire hydrant and thought it was funny and stopped to take a photograph. Police accused her of tampering with a fire hydrant, and the tense exchange that followed has stayed with her.

“It was a moment where I differently understood the privilege that I had had in earlier interactions with police officers,” she said, “and that relationship, and what was changing — and what I was witnessing, what I saw unfolding in my own body and the people in front of me.”

It can be exhausting, she said, to carry other people’s hostility, and it can make you feel divided in yourself. She recalled writers like Audre Lourde making the argument that when someone feels confident, alive and present in her own body, she can have the strength to support people around her and bring them together.

In the years after the 2016 election, being kind could feel like a revolution, Cox-Richards said. She felt such a prevailing pressure toward hostility and division that it could feel like an act of political courage to care for your neighbors, your community or yourself.

She feels a tie between caring for people and community and caring for the land. Re-using material instead of finding it new may take more time and resources, she said, but she thinks it can be healing when people look closely at what they can find around them and work with what they have.

“I think of the kudzu and tomato” frames, she said, “and the ridiculousness of trying to weave kudzu onto a trellis when it’s going to do what it wants to do — it can grow up to a foot a day. … But I was interested in kudzu because it’s a very renewable resource.

“There’s a woman named Nancy Basket who’s an indigenous woman living in South Carolina who’s an incredible kudzu weaver and basket weaver, and she has this beautiful relationship with kudzu as a material. And even though it’s so maligned as an invasive species, she says, ‘Well it’s here, and it has medicinal properties and all of these great strengths as a weaving material, as a building material, it has nutritional value, so let’s just use it.’”

She grinned at the exuberance of kudzu stars tumbling together as though they have blown or grown together.