News & Issues November 2021

Redistricting reform swiftly reaches partisan deadlock

New York panel offers competing maps amid predictions of failure

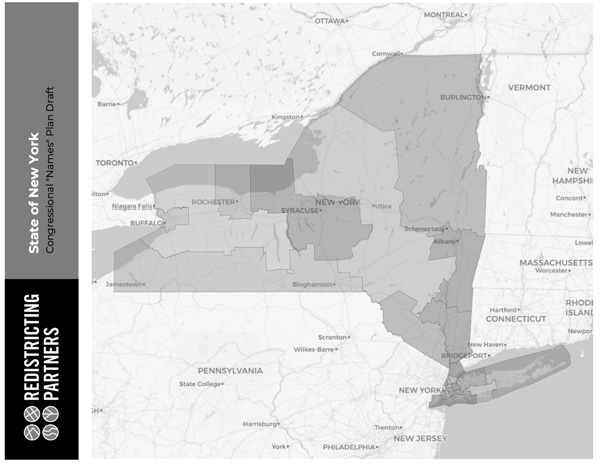

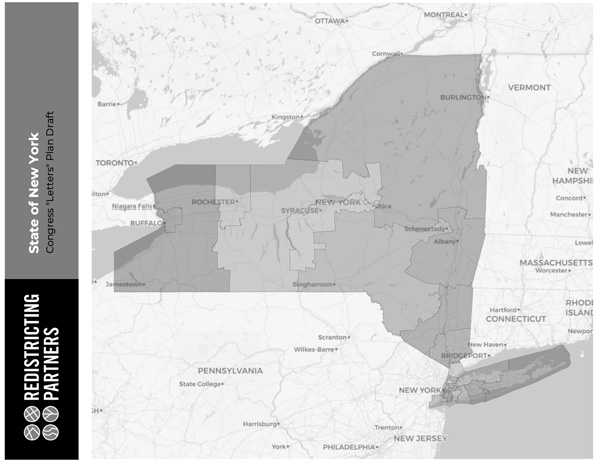

New York’s new Independent Redistricting Commission has put forth two alternatives for redrawing the state’s congressional districts. The map above was crafted by the panel’s Democrats, the one below by its Republicans.

By MAURY THOMPSON

Contributing writer

New York’s new Independent Redistricting Commission was supposed to reform the once-a-decade process of drawing new boundaries for congressional and legislative districts.

But critics say the end result of the new commission’s work is likely to be more of the same partisan gerrymandering that has been the hallmark of the state’s redistricting process for decades.

“What we’re seeing now is exactly what we predicted, which is gridlock,” said Blair Horner, executive director of the New York Public Interest Research Group.

Horner said the process so far validates his organization’s opposition to the 2012 legislation and 2014 constitutional amendment that established the independent commission.

Although good-government groups had long called for the state to set up an independent, nonpartisan process for drawing political district lines, the 2012 legislative deal that set the stage for the new commission specified the panel would be bipartisan, not nonpartisan, with equal numbers of members from the two major parties. The deal also gave the Legislature the final say on drawing the political maps in the event that the commission deadlocks.

In September, the new commission, unable to reach consensus before the start of public hearings on its preliminary plan, submitted two sets of proposed congressional maps – one drawn by Democratic members of the commission, and a separate plan drawn by Republican members.

Political leaders from both major parties are dissatisfied with the outcome.

“They need to go back to the drawing board,” said Warren County Democratic Chairwoman Lynne Boecher.

State Republican Chairman Nick Langworthy issued a press release calling the commission’s process “a political sham built on a foundation of lies and hypocrisy.”

It is still possible the commission could agree on one set of maps before a Jan. 15 deadline to submit a redistricting proposal to the Legislature. But the early conflict does not bode well for the smooth, transparent, nonpartisan process reform advocates had hoped to see.

“It could be something that goes to court,” said Jennifer Wilson, deputy director of the League of Women Voters of New York State.

Exercise in futility?

Some political observers say that because the Legislature has the final say on drawing district maps, the work of the new commission ultimately is inconsequential.

“The Legislature will be the ones who have the greatest impact,” Boecher said.

An Oct. 13 post on national political analyst Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight blog predicted said that either of the congressional maps produced by New York’s commission would be “dead in the water” when they’re submitted to the Legislature, where Democrats hold large majorities in both the state Senate and Assembly.

Silver’s blog suggested that the national Democratic Party will pressure state Democrats to draw New York’s congressional maps to the party’s advantage, because New York is basically the only state where Democrats ultimately control the map-making process and could use gerrymandering to flip several House seats to the Democratic column.

Republicans are expected to gain congressional seats through gerrymandering in some states where they control the map-making process, such as in Texas and Florida. But in several key Democratic-controlled states, including California, Virginia and Colorado, maps drawn by independent redistricting commissions cannot be overridden.

David Wasserman, an analyst for the nonpartisan Cook Political Report, has estimated that if New York Democrats use gerrymandering to maximum advantage, the makeup of the state’s U.S. House delegation, now 19 Democrats and eight Republicans, could swing to 23 Democrats and just three Republicans.

New York is losing one House seat, dropping from 27 to 26 representatives, as a result of the 2020 census. The state’s overall population actually increased by 823,000 over the past decade, to 20.2 million people, but that wasn’t quite enough to keep pace with the growth of other states. If the census had found just 89 additional residents statewide, New York would have avoided losing any of its House seats, according to data the U.S. Census Bureau released in late April.

Competing plans

Wilson, of the League of Women Voters, said that regardless of the outcome, the redistricting commission’s release of two competing plans has made the process more difficult for the public to follow. Many people will not have the patience to sift through the details of the two plans, she suggested.

“That’s a lot to ask of the average New Yorker,” Wilson said. “It’s a lot to ask of even people in the know.”

Wilson said she fears the public hearings on the proposed maps will be dominated by comments about the process instead of the particulars of either proposed map.

“They’re not going to be able to generate as good of a testimony as if a single set of maps were being considered,” she said.

In past redistricting cycles, before the creation of the new commission, the process traditionally started with two sets of maps, one drawn by the state Senate, which for decades had a Republican majority, and one produced by the Assembly, which had a Democrat majority.

The two plans set up a bartering process in which the governor had the final say.

That led to some odd results. In 2002, for example, under a deal reached just hours before the Legislature adopted the final maps, the Essex County town of Ticonderoga was split between two congressional districts, leaving one area where neighbors were in different districts depending on whether their homes were on one side of the street or the other.

But that type of last-minute deal making is much less likely this year, given that Democrats now hold veto-proof majorities in both houses of the Legislature.

Horner said the state needs to go back to the drawing board and establish a redistricting process that is totally independent from the Legislature, such as the system in California.

“That won’t be done in time for this go around,” he added.

Fallout for area lawmakers

A review of the two maps the commission has released reveals that neither party’s plan would pose much risk to U.S. Rep. Elise Stefanik, R-Schuylerville, who in May was elected to House Republicans’ No. 3 leadership post, replacing Liz Cheney of Wyoming.

Both the Democratic and Republican maps extend the boundary of Stefanik’s current 21st district south to include Gloversville and Amsterdam, the hometown of Rep. Paul Tonko, a Democrat, in a newly drawn district that would still have a heavy Republican enrollment advantage.

This has prompted some political observers to speculate that Tonko might be planning to retire, although he has not announced or hinted at that.

Under both plans, Rep. Antonio Delgado, D-Rhinebeck, would be the incumbent in a newly drawn district with a more favorable Democratic enrollment advantage.

To the west of the region, the Democrats’ proposed map would put the hometowns of Republicans John Katko, a moderate, and Claudia Tenney, a conservative, in a single district, setting up a potential primary between philosophical opposites.

But Boecher, the Warren County Democratic chairwoman, said people should not put too much stock in commission’s maps, as the Legislature likely will make the final determinations.

“They’ve got to protect Delgado, and they’ve got to protect Tonko,” she said.

The commission has a Jan. 15 deadline to submit its final proposed plan to the Legislature.

Horner said it’s possible, but does not look likely, that the commission could reach consensus on a single plan.

“If it can’t come into agreement, the Legislature will draw its own lines,” he said.

Wilson, of the League of Women Voters, said that in theory, the commission could submit more than one plan. Any proposed plan that receives at least five votes of the 10-member commission can be submitted to the Legislature.

The commission has four Republicans, four Democrats and two members who are not enrolled in either major party.

The Legislature can reject the commission’s plan by a two-thirds vote and send it back to the commission for reconsideration.

If the Legislature rejects a second plan from the commission, the Legislature would then take over the redistricting process.

In an apparent effort to give itself more latitude, the Legislature has placed a new amendment on this month’s general election ballot that would allow lawmakers to reject a redistricting commission plan by a simple majority vote.

The amendment also would clarify the time frame for the process, which is important, Horner said.