Arts & Culture October 2020

Local role in push for women’s rights

Show highlights friendship of Susan B. Anthony, Hubbard Hall founder

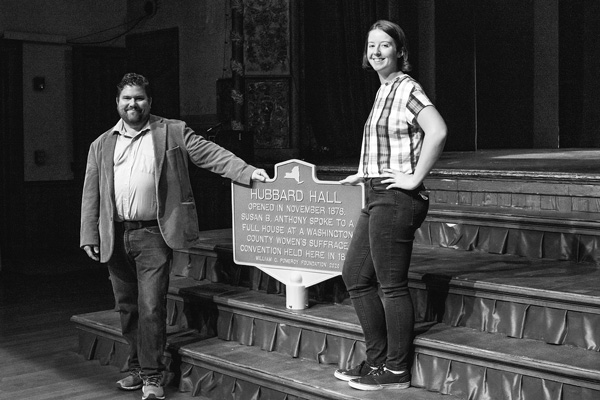

David Snider and Kathrine Danforth of Hubbard Hall display a new historical marker commemorating Susan B. Anthony’s 1894 visit to the hall as she campaigned for women’s rights. Hubbard Hall will explore the region’s role in the women’s suffrage movement in a new play, “The Susan B. Anthony Project,” with six performances scheduled Oct. 16-18. Joan K. Lentini photo

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

CAMBRIDGE, N.Y.

Women are talking in a public hall, debating passionately. They see the country at a turning point -- shaken by an impeachment, an upsurge in violence and disputes over immigration and voting rights.

The woman giving the keynote is a charismatic speaker, plainly dressed in a dark blouse and a light collar, her hair pulled back and her glasses set firmly. She has been a national political force for decades. She is a rare woman -- one who can lead a national debate and make her points with a few blunt words.

The only question left is: Are women people?

On Feb. 8-9, 1894, Susan B. Anthony held a convention at Hubbard Hall. The national movement for women’s suffrage had been under way for decades, and Anthony was touring the state, trying to get the word “male” stricken from the New York Constitution -- because every use of it barred some legal right to anyone female.

“This may be the only opportunity this generation of women will have to see the constitution so amended as to secure the rights, privileges and immunities of citizens,” the Washington County Post wrote in announcing the event.

Anthony held conventions in every county in New York. People came together in one room to talk about vital political issues that touched all of them. Then she would take their responses, and petition signatures, to Albany.

She also stirred controversy, and still does, as she publicly split from the abolitionists and women of color in the suffragist movement.

Now, 100 years after ratification of the 19th Amendment, which finally gave women nationwide the right to vote, David Snider is aiming to rekindle the energy and debate that led to that achievement.

Snider, the executive and artistic director of Hubbard Hall, has spent two years exploring the local history of the women’s suffrage movement. Starting last fall, he began organizing a series of workshops where adults and public school students explored that history and its meaning for today. He collected hundreds of pages of thoughts, and from them he created a script, a new play with music and voices of people who helped to reshape the nation – people such as Anthony, Sylvanie Williams, Sojourner Truth.

Over the summer, as Black Lives Matter protests brought new urgency to questions of equality and civil rights, Sydney Helsop, a student at the University of Albany and a writer of color, began working with Snider, writing from her own perspective and experience.

The result is a 90-minute show, “The Susan B. Anthony Project,” with original music by Bob Warren, that will have six performances Oct. 16-18 on the hall’s main stage, the first theater inside the hall since the pandemic.

Three professional actors will perform as historical and contemporary women: D. Colin, a slam poet and artist from Troy, Christine Decker, an Equity actor in Cambridge, and Vivian Nesbitt, a performer from Saratoga Springs. They will join a cast of local youth actors as they explore what rights and freedoms -- and voting -- can mean today.

History and social justice

The show originally was scheduled to debut in the spring but was postponed because of Covid-19. This month’s performances, the first professional theatrical production inside the hall since the pandemic began, will have physically distanced seating, mask wearing and fans and open doors to increase air circulation.

In early March, Snider sat down to talk at the former Round House Bakery Cafe, which occupied a storefront space in the Hubbard Hall complex but has since closed permanently because of fallout from the pandemic. He said preparing for the show had given people a chance to explore history in more depth than a school class often allows.

“It is important to talk about history through a lens of social justice,” he said, to get into the whys, not the series of battles we all memorized.”

He talked with students about the wage gap, how much women make as opposed to men, how much women of color make. And he said he realized that many of them had not talked about these issues in class. Often they had not known or thought about them at all.

Some of the responses he has heard have shaken and troubled him, especially those from young women who seemed to have absorbed negative stereotypes without realizing or questioning them.

One young woman explained the wage gap by saying, “It’s because women don’t want to work as hard.”

Understanding these issues matters on a national scale, Snider said.

“As we witness a Supreme Court that may lead to curtailing women’s rights across the nation,” he wrote in an introduction to the performance, “and as we have a president who has demonstrated what can only be politely called a lack of regard for women’s rights in our society, the work of Susan B. Anthony, the women’s suffrage movement and the fight for equal rights for all is perhaps more relevant and important than ever before.”

As Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death has brought those questions still closer, he has brought her into the script as well. He hopes, he said, that the script will always live and evolve.

Rediscovering Mary Hubbard

To learn about Hubbard Hall’s role in the history of the suffrage movement, Snider began combing through the archives of the Washington County Post, a local newspaper that published from 1837 to 1988, and consulted other local history resources.

And his research led him to a central voice in the hall’s own history that he had not heard before: He encountered Mary Hubbard, the artistic director who brought Susan B. Anthony to Cambridge.

Mary Hubbard ran Hubbard Hall for 25 years in its heyday. She took over after her husband, Martin, died, and Snider believes he may have built it for her.

In her hands, the hall became a vibrant place, Snider said. He has found records of the performers she brought.

A few months after the convention, the South African Native Choir came to perform, with members who would go on to become leading activists and reformers. In his introduction, Snider tells the story of Charlotte Manye Maxeke, who worked to educate thousands of young African students and became a passionate advocate for the African National Congress, South African women’s rights and African freedom.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers, from Fisk University in Nashville, sang spirituals at Hubbard Hall as they traveled the world.

Vida Goldstein, a newspaper editor and a delegate to the International Women’s Suffrage Conference from Australia, came to give a talk here in 1902. She had addressed members of Congress in Washington before proceeding on a speaking tour around the Northeast.

Hubbard invited musicians and theater people with their own shows.

Luci Nicolar, a Penobscot actor from Maine, toured nationally and in New York as an actor, mezzo-soprano and activist for her people.

Carolina Mohawk, an actor and athlete, writer and director born to the Seneca Nation at Cattaraugus, created her own new works.

Mary Scott Siddons performed Shakespeare.

And a few months before Anthony stood at the lectern, Camilla Urso, one of the first women in America to perform violin onstage, held another audience rapt. Urso had been the first girl to study at the Paris Conservatory, and she performed here, in the Post’s recounting, with an ardent force that brought the overwhelmed crowd to their feet -- though they were businessmen and country people, not classical music fans.

They might never have heard the Grand Fantasia from “Faust” before, the works by Bach, nor Paganini’s violin variations on “The Carnival of Venice.” Urso ended the evening with an encore, simple but just as strong: the Irish song “The Last Rose of Summer.”

Mary Hubbard brought Hubbard Hall to life and filled it, even when the performances surprised and challenged her neighbors.

She also built it up physically, expanding the stage and the proscenium, Snider said. She added a green room and collaborated with the chief scene painter for all of the theaters in the region.

“She was making it a gem to attract world-class artists in a way Martin didn’t,” he said. “She invested in it. She had that kind of savvy.”

History of the Hall

In the late 19th century, it was remarkable for a woman to have the authority to decide the programming in a space like this, Snider said. At the time, women artistic directors of theaters were very rare in the United States.

It was doubly remarkable that Hubbard had the hall at all.

Her husband, Martin, died in 1884, Snider said, six years after the hall opened. And when he died, the village took all of his estate from her, claiming that as a woman, she had no right to inherit it. She took the case to court and eventually won, though it took several years before she could claim the hall as her own.

The fight was worth it, as Mary Hubbard proved to be a smart and adept manager.

In the 1880s, community halls and performance spaces were flourishing, Snider said. Every village had a hall like this. Hubbard Hall is now the only one in Washington County, and it’s close to its original condition.

Cambridge grew as a stop on the stagecoach route between New York City and Montreal, but Snider said it had a deep divide between the east and west sides of town. The east side, where Hubbard Hall stands, was the dry end of town. The west side had the saloons and hotels.

The west end also had its own opera house, but he describes it as a very different place -- rougher, with hooligans and drunkards hanging out on the steps. He is not surprised that it burned down in the 1890s.

At the east end of town, Mary and Martin were prohibitionists who supported the Congregational church across the street, Snider said. Martin Hubbard was a dry businessman, 20 years older than his wife. He owned the office space around the hall, including the general store and a lumberyard, a significant property on this side of Main Street.

Snider sees Mary at the heart of the theater from the beginning.

“She may have been the driver,” he said. “She may have said, ‘This is what we need for me to be happy here and intellectually engaged.’ She understood in 1878 that in order to have quality of life, they needed an arts center.”

In the 1880s, Snider said, theater was surging as the United States was in the process of creating a cultural identity separate from Europe’s. It was also the beginning of the Jim Crow era, the years when the liberal beginnings of Reconstruction were rolled back. Hubbard brought in performances of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” but she also brought in minstrel shows.

“She was not just a clear-eyed progressive,” Snider said.

But she brought voices and debates and a creative spirit her community might otherwise never have heard or known existed.

After Mary died, Snider said, the hall gradually dimmed and went dark. Vaudeville was fading, and a movie theater opened in town. By 1927, Hubbard Hall had closed, and it sat empty for 50 years. And so her name and her history faded into the clipping files in the local newspaper archive.

When Snider came to Cambridge, he said, people in town told him about Martin Hubbard, but no one ever talked about Mary. No one seemed to remember her.

He has not yet found a single photograph of her.

Histories lost and reclaimed

Histories can be lost, Snider said. Sometimes people suppress them deliberately. Sometimes no one thinks to preserve them.

He described a community play, like the one he is creating now, that he developed on Woodlawn Cemetery in Washington, D.C. The cemetery lay behind his house, with 30 acres and 36,000 burials going back to 1791.

John Mercer Langston is buried there, the first black man elected to Congress from Virginia, in 1888. Mary Hubbard could have read about him in her morning paper as she prepared for the convention.

Blanche Kelso Bruce is buried in Woodlawn too, the first black U.S. senator to serve a full term. He had been born in slavery, and in freedom he grew to become a wealthy landowner and represented Mississippi in Congress from 1875 to 1881.

When Snider brought this project into the school up the street, students in his neighborhood learned Bruce’s history for the first time -- even though their school was named for him.

He has been struck in the same way, as he’s discovered what people don’t know about women’s rights, what they have never had a chance to learn, even when the stories unfolded under their feet.

He has led workshops in schools about women who led the movement, including Susan B. Anthony and Sojourner Truth.

By 1894, Mary Hubbard was active in suffrage campaigns around the region, and she and Susan B. Anthony had become friends. They went to Washington together several times to attend national gatherings of the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

By then the movement had also suffered divisions. Some women’s rights activists also supported abolition and the rights of black Americans, but tensions surfaced on both sides. In 1870, the 15th Amendment affirmed that black men had the right to vote, but it did not extend the vote to women.

And black women faced their own challenges.

“People were left behind by the movement,” Snider said, “and it is still true today. Even in 1920 [with adoption of the 19th Amendment], women of color were never brought to the same level as white women, and the damage reverberates today in income, in the wage gap, in childbirth and mortality rates. … People like Stacey Abrams are still fighting having an election stolen from them by voter suppression.

“We are grappling with this in an election year,” Snider said. “Where is suppression now? What would Mary and Susan be doing today if they were still here? The fight for women’s rights is not yet done.”

Hubbard Hall will present six performances of “The Susan B. Anthony Project” from Friday, Oct. 16, through Sunday, Oct. 18, on its main stage, with tickets reserved ahead. The Hall also plans to film the performance to stream online. For reservations and updates on the film, visit hubbardhall.org or call 518-677-2495.