Arts & Culture April 2020

Retracing a family’s roots — and uprooting

Illustrator’s memoir draws on childhood in wartime China

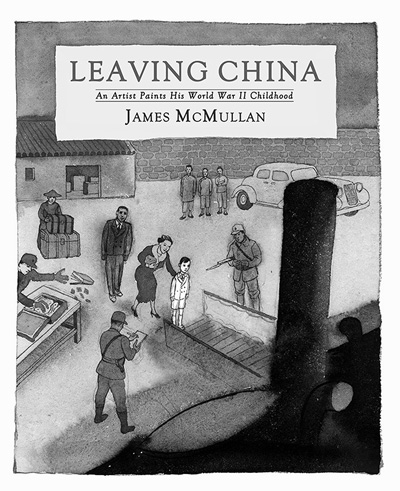

James McMullan’s memoir tells the story of his family’s life in China and his childhood there amid the Japanese occupation of 1937-41. Courtesy photo

James McMullan’s memoir tells the story of his family’s life in China and his childhood there amid the Japanese occupation of 1937-41. Courtesy photo

By JOHN SEVEN

Contributing writer

STOCKBRIDGE, Mass.

With a family story centered on China that stretches back 100 years, illustrator James McMullan is coming to the Norman Rockwell Museum to talk about his book that chronicles that tale.

“Leaving China” tells the story of McMullan’s family’s life in China, from his grandparents’ missionary work for the Anglican Church, starting in the late 19th century, through McMullan’s childhood and eventual flight during the Japanese occupation and beyond.

McMullan’s grandparents, James and Lily, began to expand their mission to support efforts to save baby girls who were being left to starve to death. This led to them to raise funds and open an orphanage and school.

After infanticide ceased to be a problem, Lily taught the orphaned girls embroidery skills that used silk and cotton produced in the region, providing them with important job skills that funded the orphanage and led to an industry that still exists.

“The book was not published in China, but it was published in Korea, and it got to China,” McMullan said. “I got these amazing emails from this woman who works at an embroidery place as a kind of executive, and she said, ‘You may not realize this, but we hold your grandmother in great esteem because we feel that she really started this business which we are still making our livings from.’”

The family business expanded to the next generation, with McMullan’s uncle developing James McMullan Agencies, which sold insurance and Ford cars, printed newspapers, and imported goods.

McMullan’s father was a musician who went to Canada but returned to China with a wife and two stepchildren. McMullan was soon born, and this is the world he grew up in.

McMullan, now 85, began toying with a memoir through illustrated stories and artwork that go back to his days in art school. Working from his father’s letters, memoirs written by relatives, and historical accounts of his grandmother’s work with the embroidery factory, McMullan combined these accounts with the intensity of his own childhood trauma, which had branded itself into his memory.

“The thing in the book where the sound of these Japanese soldiers going around in these squads and doing their chants at night was very, very frightening to me,” McMullan said. “And I’m like most kids that when your parents try to keep things from you, you have a sense of that. And it makes it worse, the idea that something is happening that’s so bad that the parents are lying and not talking about it and when you come in a room, they’re hushing up.”

Fleeing war, discovering art

In fighting that began in July 1937, imperialist Japan invaded China and scored a series of military victories, capturing and occupying major cities including Beijing and Shanghai and forcing the Chinese central government to retreat to the interior of the country. The occupied territory included Tsingtao, where McMullan’s family lived.

“There’s a lot about the years from 1937 to 1941, where the Japanese had taken over that town, that was a big part of my childhood anxiety, just knowing that this bad stuff was happening and my parents were trying to protect me from it,” McMullan recalled. “So I just think I grew up with some floating anxiety.”

McMullan and his mother eventually fled to stay with relatives in Canada, while his father joined the Royal British Army. McMullan saw his father once more while he and his mother stayed in India. His father died in a plane crash in 1945 after the Japanese surrender, and McMullan and his mother left for North America for good.

McMullan was living on Salt Spring Island, off the coast of British Columbia, with his aunt and uncle, when a Saturday Evening Post subscription opened up possibilities he never knew existed.

“That’s when I realized, ‘Boy, there’s something in the world called an illustrator, and boy, look at what they’re doing,’” he said.

McMullan attended the Corner School of Allied Arts in Seattle and later switch to Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. While there, he started getting illustration work for Harper’s Magazine. After graduation, he got an unusual big break: drawing the covers for Everyman’s Library, a literary reprint line from E.P. Dutton.

“They were really interesting books, and it suited me very well,” McMullan said. “They’re all very arty and far out, but he let me do it. And that was, as I began to understand that that’s my thing. I like reading. I like thinking about complex subjects and reducing them to one image. That’s what suits me.”

Filling Warhol’s shoes

McMullan had difficulty getting work with ad agencies, because his art was not considered very commercial. At one point an agent accidentally placed photostats of his illustrations in the back of someone else’s portfolio. The agent got a call from the art director at I. Miller, the shoe manufacturer, seeking to hire not the portfolio artist, but whoever had done the work in the photostats.

Andy Warhol had just left I. Miller to pursue fine art, and McMullan was his replacement.

“I did these crazy drawings for I. Miller Shoes, and I think I got maybe five of them into The New York Times, big ads in The New York Times,” he said. “The guy that owned I. Miller said, ‘What the hell is going on here?’ I got fired right away. The art director got fired too.”

It wasn’t the end of his career, though, and McMullan went on to further magazine illustration, including for Sports Illustrated. He also signed onto Pushpin Studios for three years, working alongside the studio’s two owners, Milton Glazer and Seymour Chwast.

In 1976, he illustrated the article “Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night” for New York Magazine. The article, by Nik Cohn, became the inspiration for the film “Saturday Night Fever.”

McMullan has also made a career of theatrical posters, creating more than 80 for Lincoln Center. He’s currently working on one for a new play from Sarah Rule called “Becky Nurse of Salem.”

In the 1990s, McMullan began illustrating children’s books in collaboration with his wife, writer Kate McMullan, starting with 1992’s “The Noisy Giants’ Tea Party.” They’re currently working on a book about democracy, aimed at second-graders, that will explain the political system in terms of interactions that happen to kids of that age.

McMullan’s family history did come up one more time in his life, in 1952, while he was in the Army after he and his mother emigrated from Canada to the United States. McMullan worked in a unit in North Carolina that was focused on psychological warfare, typically creating diagrams of loudspeaker placement on Sherman tanks and crafting instructions on how to prepare leaflets to be thrown out of planes across enemy lines.

One day his commanding officer informed him that his security clearance was revoked because it had been discovered that he was a “communist landlord.”

McMullan’s father had inherited property from his brother but lost it when the Japanese invaded. Years later, the property became linked to McMullan on paper.

“The colonel realized how ridiculous it was,” McMullan said. “He said just keep doing what I was doing but just don’t tell anyone that I was dealing with somewhat secret information. That was my experience in the Army. A lot of rather dumb things went on.”

As of late March, McMullan was still scheduled to discuss his picture book “Leaving China” at 1 p.m. Sunday, April 19, at the Norman Rockwell Museum – and to conduct a master class at 10:30 a.m. April 18 at the museum. The museum has been closed since March 13 because of the Covid-19 outbreak; it plans to re-evaluate its schedule on April 1. Please visit www.nrm.org for updated information on the timing of McMullan’s visit.