Editorial September 2018

E D I T O R I A L

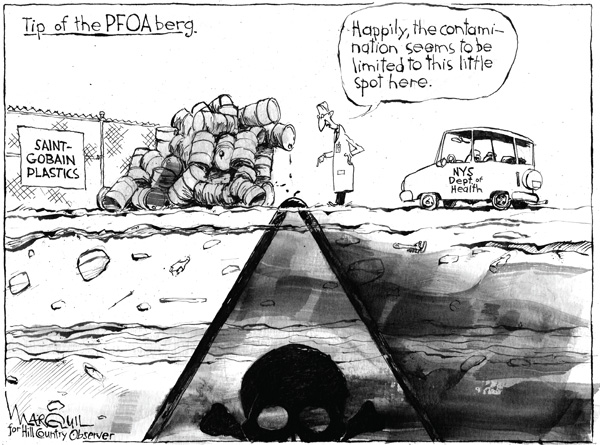

State’s claims on cancer belied by new PFOA study

When Michael Hickey, a former village trustee in Hoosick Falls, decided to have his tap water tested for perfluorooctanoic acid in 2014, he was searching for an explanation for what he and others believed was a high local incidence of cancer.

Hickey’s father, who had worked at a local factory that used PFOA, died of kidney cancer. Hickey consulted with a local doctor, Marcus Martinez, who had just undergone treatment for a rare form of cancer. They knew stories of family members and friends with no known risk factors who developed rare or highly aggressive cancers.

So it seemed to explain a lot when Hickey’s water test showed PFOA at a concentration of 540 parts per trillion -- well above what was then the federal government’s advisory safety limit of 400 ppt. (The federal safety limit has since been lowered to 70 ppt, while Vermont’s is just 20 ppt.)

Health studies done about a decade ago in the Ohio River valley – in an area near Parkersburg, W.Va., with extensive PFOA contamination of drinking water supplies – established a probable link between PFOA exposure and kidney and testicular cancer and several other health problems.

In Hoosick Falls, although PFOA had been used for decades in local factories, including at a plant right next to the village’s water wells, it seems no one thought to look for it in the municipal water supply before 2014. PFOA wasn’t among the contaminants for which the village was required to test, so it didn’t. A filtration system installed in 2016 now keeps PFOA out of the tap water, but no one knows for how many years before 2014 people in Hoosick Falls were consuming tainted water.

Last summer, though, New York’s top health officials sought to reassure everyone. The Department of Health announced it had reviewed the state’s cancer registry from the past 20 years and found that, amazingly, the incidence of kidney and testicular cancer in Hoosick Falls was actually lower than what would be expected for a community of its size. The village does have a high incidence of lung cancer, the state said, but there’s no scientific evidence linking lung cancer to PFOA.

Strangely, lots of people weren’t reassured. This conclusion was, of course, coming from the same Health Department that insisted for more than a year in 2014-15 that the village’s water was safe to drink, despite evidence to the contrary presented by Hickey and others. The state didn’t change its stance until federal environmental officials stepped in at the end of 2015 and said flatly that the water wasn’t safe – and that the public needed to be told.

Now the state’s cancer conclusions are similarly being called into question. As our cover story this month details, a team of professors and students from Bennington College, working with other scientists and former government regulators in the region, undertook a door-to-door health survey last winter in Hoosick Falls and two other local communities affected by PFOA contamination. Although only 10 percent of the population in the three communities participated, in Hoosick Falls alone the survey documented more cases of kidney and testicular cancer than the state reported.

Consider: The state reported there’d been 12 cases of kidney cancer in Hoosick Falls, but the college’s researchers found 17. And the state reported no cases of testicular cancer in Hoosick Falls, but the new researchers documented nine.

If the state hopes ever to regain its credibility in Hoosick Falls, its study of PFOA cancers will need to consist of more than culling some numbers from a database and calling it a day.