News & Issues June 2017

Unforgettable lessons

Teacher’s living-history project puts faces to World War II, Holocaust

By STACEY MORRIS

By STACEY MORRIS

Contributing writer

HUDSON FALLS, N.Y.

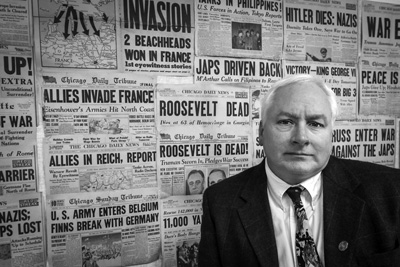

Matthew Rozell, a high school history teacher in Hudson Falls, stands in front of a classroom display of newspaper front pages from the World War II era. He will retire this month after 30 years of teaching, but he plans to continue collecting the accounts of World War II veterans and Holocaust survivors. Joan K. Lentini photo

Matthew Rozell began to discover his mission in the late 1980s as a young history teacher at Hudson Falls High School.

Frustrated by the limited time available to cover a topic as complex as World War II, Rozell came up with a way to supercharge the learning experience: by having his students interview the war’s veterans face to face and report back on what they had learned.

“In those days, there were still quite a few World War II veterans, and the kids really responded to getting to know their personal stories,” Rozell recalled. “It was a sea-change for being a history teacher. … Even problem kids would listen up.”

He soon found this approach had benefits beyond capturing his students’ attention and imagination. Rozell became so interested in the stories collected by his students that he began interviewing veterans himself, at their homes and in question-and-answer sessions with his classes.

“A lot of veterans are able to talk openly to teens in a way they wouldn’t talk with their own family,” Rozell explained. “After the war, they plunged back into life: working, raising a family. We found that veterans are more willing to talk to young students because they want to impart unknown information. It’s beneficial to both parties.”

Over the years, Rozell and his students collected the stories of hundreds of World War II veterans, mainly from Warren and Washington counties. They were able to fit those stories into the larger context of the war’s history – and to document some details of the war that weren’t widely known.

With the advent of personal computers and the Internet came a way to catalog the years of interviews with veterans – and also to share those stories around the world through the Web site of what became the Hudson Falls High School World War II Living History Project.

And about 15 years ago, Rozell’s work took on a new dimension when one Army veteran recalled how he and his fellow soldiers rescued a trainload of 2,500 Jewish prisoners who were being shipped from one concentration camp to another in the final chaotic days of the Nazi regime.

Rozell and his students were able to interview other soldiers who took part in the rescue, as well as some of the Holocaust survivors they freed. Over the past decade, the school’s living-history project helped to reunite some 250 survivors of the Nazi death train with the American soldiers who became their liberators, and Rozell documented their stories and details of the episode in “A Train Near Magdeburg,” a book he published last year.

A race against time

After 30 years of teaching at Hudson Falls High School, Rozell is preparing to retire this month. Hudson Falls is his alma mater, and his father taught world history at the same high school for many years.

As he prepares to leave his classroom for good at the end of the school year, he is packing up a series of accolades and mementos. There are Teacher of the Year awards, commendations from various historical organizations, and his collection of newspapers from the World War II era. At one point in 2009, ABC World News named Rozell its “person of the week.”

Rozell, of course, isn’t just trading in his blackboard for a set of golf clubs. At 56, he says he has begun to see time as a precious commodity.

As the number of living veterans of World War II continues to dwindle, Rozell plans to use a significant chunk of his newly free time to expand the interviews and archives that have garnered him recognition far beyond Hudson Falls.

Rozell’s interviews with World War II veterans became the basis for his first book, “The Things Our Fathers Saw: Voices of the Pacific Theater,” which he published in 2015.

A second volume of this work, “Voices of the Mediterranean/European Theater,” will be released in August, and a third volume, “Voices of the European Theater,” is scheduled for release in 2018. Rozell said he intends to continue the series.

His passion for bringing history to life has inspired a generation of local students, and at least one of his current students hopes to follow in Rozell’s footsteps.

Austin Underwood, a high school senior who has studied with Rozell for the past three years, is currently enrolled in his course on World War II and the Holocaust, for which there’s always a waiting list.

“One could spend their entire life studying this war and probably still not learn all that there is to learn,” Underwood said in an e-mail interview.

Underwood said he was so influenced by Rozell that he plans to attend the State University of New York at Geneseo, where Rozell studied, with the goal of becoming a teacher.

“He has preached on the importance of studying history and not letting the stories of the past be forgotten, which I think is an immensely important lesson,” Underwood said.

Death train to freedom

The story told in “A Train Near Magdeburg” began to emerge in the summer of 2001, when Rozell was interviewing Carrol Walsh, who had served in the Army’s 743rd Tank Battalion and was the grandfather of one of Rozell’s students.

The lengthy interview covered Walsh’s detailed recollections of confrontations with the Nazis as American troops pushed across northern Germany toward Berlin in early 1945.

Then Walsh’s daughter suddenly asked whether her father had remembered to tell the story about the train. The prompt from his daughter opened a floodgate of recollections from Walsh – and revealed some little-known details about how the Nazis had handled their Jewish captives near the end of the war.

“The big question at that moment was: Who was going to get to Berlin first?” Rozell explained. “Hitler was the prize that both the Americans and Russians wanted.”

It was the spring of 1945, the gruesome Battle of the Bulge was just over, Rome had fallen, and there were more than a few frays in the fabric of the once-mighty Third Reich.

“The Nazis were unraveling, but there was still resistance,” Rozell said. “The Russians were coming from the other direction across the Elbe River, President Roosevelt had just died, and Walsh’s battalion was on their way to Magdeburg to fight it out with the Germans, who had no intention of surrendering the town.”

En route to Magdeburg, Walsh and his fellow soldiers found an abandoned chain of cattle cars parked on some railroad tracks. They soon discovered the cars were filled with about 2,500 captive Jews of all ages. Most were alive, though some had died of illness or starvation. In unusual circumstances, the train had been heading away from the infamous Bergen-Belsen death camp rather than toward it.

Besides fighting back the Allied troops, the Nazis were busy destroying as much evidence from the Holocaust as they could, razing many of the camps and subcamps as well as their crematoriums. Rozell said the Nazis also had a sudden interest in preserving their captives.

“The S.S. in Berlin were ordering their troops to move their captives from point A to point B,” he explained. “The plan was to use them as bargaining chips if needed. It was utter chaos in Germany.”

Because of the tumultuous conditions, the train ride from Bergen-Belsen to Magdeburg, which normally would have taken about an hour, lasted nearly an entire week, with the train’s occupants confined in the dark without food or water, constantly hearing explosions in the distance.

Just outside Magdeburg, the Nazis realized the Allies were closing in. They abandoned the train, leaving its occupants, most of whom were malnourished to begin with, for dead.

“A Train Near Magdeburg” was inspired by Rozell’s interviews with Walsh and another tank commander, George Gross, and by a photo taken by Gross. Walsh and Gross were charged with looking after the survivors found inside the cattle cars, and Gross took the first of a series of photographs of the dazed captives with his Brownie camera minutes after they were freed.

“This picture defies expectations,” Rozell explains in the book. “When the terms ‘Holocaust’ and ‘trains’ are paired in an online search image, the most common result is that of people being transported to killing centers. But this incredible photograph shows exactly the opposite.”

To overlay an order to the war’s jigsaw puzzle of details, Rozell divides his 500-page book into four sections: the Holocaust; the Americans; Liberation; and Reunion. The pages within are filled with accounts of 15 liberators and more than 30 Holocaust survivors.

Reuniting captives, liberators

Part of what sets Rozell’s work as a historian apart has been his effort to reunite Holocaust survivors with their liberators. The idea for these reunions took hold after Gross’ photos of the Magdeburg incident were posted in 2002 on Rozell’s Web site, which had already drawn attention from Holocaust survivors around the world. Survivors of the Magdeburg train soon began contacting Rozell.

He organized the first reunion of Holocaust survivors with their rescuers in 2007. After the event was covered by the Associated Press and picked up by newspapers around the world, the reunion generated so much interest that Rozell’s Web site crashed.

“When I went back to school on Monday, everything had changed,” Rozell recalled. “More than 300 e-mails had come in over the weekend. The Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C., invited me to study with them that summer. I knew I was entering a different universe.”

Ariela Rojek was 11 when American soldiers rescued her from the Magdeburg train. A native of Poland, she lost all but one family member – an aunt who was traveling with her on the train -- in the Holocaust. Rojek had spent two years at Bergen-Belsen before being loaded onto the train. By then, she had typhoid fever and was weak and barely conscious.

“For the first time in my entire life, I felt like someone actually cared about me,” she recalled in a phone interview from her home in Toronto. “That’s what the American soldiers did for me. They were my angels.”

Rojek vividly remembers the first reunion she had with her rescuers – at an event organized by Rozell.

“I talked to one of the soldiers who was a medic,” she said. “He was 94 and remembers everything exactly from that day, just like I did. It was a very pleasant reunion, and I consider Matt Rozell to be an angel, just like those soldiers.”

Rozell said there is “always more to learn” on World War II and the Holocaust, and he has traveled to many of the sites he writes about, including Bergen-Belsen in Germany, Auschwitz and Majdanek in Poland, and Theresienstadt, the site of a concentration camp in what was then German-occupied Czechoslovakia. Last summer, Rozell was awarded a scholarship by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust remembrance center in Jerusalem, to study Holocaust history throughout Israel.

After writing his first book, Rozell said he realized he’d only captured a fraction of the details of the war. Even as his third book was recently completed, he says there’ll be at least three more.

And besides more writing, he plans more travel abroad for research and speaking engagements.

Rozell said he was recently contacted by a councilman from Magdeburg and asked to come and speak about his new book.

“In Germany, there’s a hunger for this kind of information,” he said. “The second generation didn’t talk about it.”

His work has drawn international attention from history buffs and family members of Holocaust survivors and World War II soldiers. He also receives messages occasionally from members of another contingent: deniers of the Holocaust.

“They’re always anonymous,” Rozell said, shaking his head.

Sunny Buchman, a retired teacher in Glens Falls who has known Rozell for years, served as a liaison between Rozell and many of the local veterans he interviewed, because many of them lived at her retirement community.

“There were so many under one roof, I thought it would be a great opportunity for Matt and his students,” she said.

With the release of “A Train Near Magdeburg,” Buchman invited Rozell to speak at her synagogue on June 11.

Despite his years of study of World War II, Rozell said compiling and organizing the book was a big challenge.

“There are so many different details to that time in history, and not all the information out there is 100 percent accurate,” he said. “The magnitude of it staggers the brain. How do you kill 6 million people over five years? How does that work?”

No matter how much research is done, it seems that will forever remain an unanswerable question.

History teacher and author Matthew Rozell will discuss his book, “A Train Near Magdeburg,” at 7 p.m. Sunday, June 11, at Congregation Shaaray Tefila, at 68 Bay St. in Glens Falls. The presentation is free and open to the public. Visit www.teachinghistorymatters.com for more information.