Arts & Culture August 2017

Capturing moments of life

Exhibit samples Vermont themes in vast oeuvre of photographer Kalischer

By KATE ABBOTT

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

BENNINGTON, Vt.

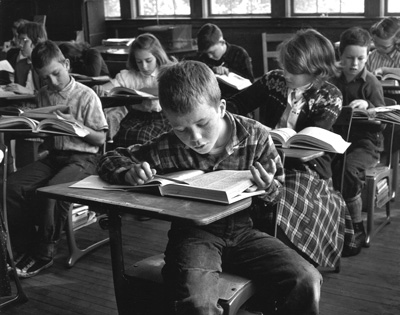

Clemens Kalischer’s photo of a one-room school in Peacham, Vt., was one a series he took in 1958 for Vermont Life and is featured in a current exhibit of his work at the Bennington Museum. Copyright 2017 Clemens Kalischer/courtesy Image Photo

At the Old Bennington Weavers textile mill, looms hold fabrics for an artist and fashion designer, Tzaims Luksus, known for his graphics on silk.

In Brattleboro, artisans at the family-run Anderson Pipe Organ Co. are shaping pipes by hand from sheet metal.

Crafters go about their work, and gray-haired men lean on their snow shovels after digging out from a storm. Students lean over their desks or musical instruments, candid and natural.

They look out of black-and-white photographs with a quiet humor, a sense of family closeness, a sense of skill and knowledge, and even a sense of loss. They are New Englanders in “Between Past and Future: Clemens Kalischer’s Vermont,” an exhibit that runs through Sept. 4 at the Bennington Museum.

As a photographer and photojournalist, Clemens Kalischer has traveled the country and world -- on assignment for The New York Times, Newsweek, Time, Yankee Magazine, The Boston Globe, Ploughshares, Orion Magazine and many others -- and on his own for the love of it. [He also took a series of assignments for the Hill Country Observer from 2006 until 2011.]

Kalischer, 96, has lived since the early 1950s in Stockbridge, Mass. There, surrounded by his prints at his Image Gallery on Main Street, his daughters, Tanya and Cornelia Kalischer, recently discussed his life and work – setting a wider context for the photographs in the Bennington exhibit.

Clemens had begun taking photos in Vermont on his own as early as 1947, Cornelia said. He felt drawn to its small towns and a sense of its political and intellectual community. He liked its mix of mills, farms and self-contained town centers.

Tanya worked with her father’s assistant, Kate Coulehan, and Bennington Museum’s executive director, Robert Wolterstorff, to curate the Vermont show. They looked through a vast collection of vintage prints -- Clemens always made his own silver gelatin prints from his own negatives – to choose the 36 images for the exhibit, said Bennington Museum curator Jamie Franklin, who shaped the exhibit as he set the prints on the museum walls.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, Kalischer was exploring Vermont in an era of change, Franklin said. The state’s traditional ways of life crossed paths with contemporary influences, and the contrasts are visible in the images -- dairy farms and Modern architecture, mill workers and a growing cultural community. Kalischer knew that community from the inside, Franklin said.

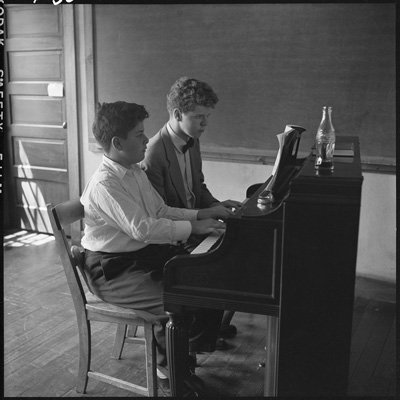

In one of a series of images from the early years of the Marlboro Music Festival, for example, he caught two boys playing a piano duet -- James Levine and Van Cliburn. One would grow up to be director of the Metropolitan Opera and the Boston Symphony Orchestra; the other would become an internationally known pianist. But here they sit side by side on a piano bench on a summer afternoon, quietly concentrating on the music they are playing.

Tanya Kalischer said her father came north on regular assignments for Vermont Life from 1956 to 1988 and also made many visits on his own. She and Cornelia have gone back with him in recent years.

“It’s his homeland,” she said.

The Green Mountains felt close to places he had known as a child in Europe, Cornelia said, both in its sensibility and landscape and in the way he felt as he explored the back roads, talking with people.

Flight and captivity

Kalischer was born in Lindau, Germany, on Lake Constance. His family moved to Berlin when he was 9, and there they lived in the Weisse Stadt (White City), a neighborhood of 1920s Modernist apartment buildings he remembered warmly later in life.

In 1933, when he was 12, his family fled Germany to escape the rising Nazi government. They left so suddenly and secretly, Tanya said, that Clemens could not tell his friends or say goodbye to them. He and his family went to Paris, where they struggled at first. The family did not have enough to eat, she said, and Clemens lived for awhile apart from them in Basel, Switzerland.

Near the house where he was staying there, he could hear the young pianist Rudolf Serkin playing music, practicing, with violinist Adolph Busch. They would become internationally known musicians, and they had also just left Germany to escape the Nazis.

Decades later, Serkin and Busch founded the Marlboro Music Festival at Marlboro College in Vermont. Clemens would photograph Serkin there and return to the festival over many years, and he and Serkin would become close friends.

But in France, Clemens and his family had not yet escaped danger. In 1939, Clemens was biking in the countryside with a friend when they saw posters telling foreign nationals to report to the nearby town hall.

He did, and he was taken prisoner. He had no way to contact his family, and without warning he was sent to a work camp on his own. He spent three years in eight different work camps -- French camps, because he was German, and France and Germany were at war.

He was forced into different kinds of heavy labor, Tanya and Cornelia said, including time in a factory where the laborers were on their feet 16 to 18 hours a day. Exhausted, he finally refused to work, and others joined him. They were going to be court-martialed, Tanya said, but under the threat of enemy planes, he and his fellow workers were evacuated to southern France.

There, under the fascist Vichy government, he was marked as a Jew. But it was there that he finally ended up in the same camp as his father. They were working long hours with little to eat, Tanya said.

When his family reunited and left the country with the help of friends, Clemens weighed only 88 pounds.

Discovering photography

Kalischer was 21 when his family came to New York in 1942. He spoke French and German but no English, and once again he and his family had to find their way in a new country. He got a job working at Macy’s to support himself day-to-day.

He was not a photographer then. But he carried a book that had survived with him all the way from Paris – “Paris Vu Par,” a collection of images of the city by the Hungarian photographer André Kertesz. In New York, a fire mostly destroyed it, Cornelia said, but a few years ago she found another copy for him for his 90th birthday.

Chance encounters encouraged his interest, and he followed it to courses with the Photo League, a photographers’ cooperative that provided him with use of a darkroom.

There and in many other settings, he learned from other students and enthusiasts. He studied at Cooper Union, and in an interview in Hatje Cantz’ book, “Clemens Kalischer,” he recalled 30 or 40 students gathering at a coffee shop after a class at the New School to talk about their work.

But often, Kalischer learned by himself. He met a range of well-known photographers in those years, from Berenice Abbott and Ansel Adams to Edward Steichen.

Steichen, as photography director at the Museum of Modern Art, chose one of Kalischer’s images for the 1955 exhibition “The Family of Man.” The show toured the world for eight years, and its photos were collected in a book of the same name. Beaumont Newhall, the first photo curator at MoMA, also had included Kalischer in a large photography exhibit, “Out of Focus,” in 1947.

Kalischer worked his way to early assignments at the Agence France-Presse and later established a decades-long relationship with The New York Times. Often one of his photographs would draw attention from another photographer or an editor, and he began to build a freelance career while also pursuing his own photographic subjects -- out of love and fascination and a need to see clearly.

He would wander through the city, Tanya and Cornelia said, photographing longshoremen unloading grain sacks, a young shoeshine boy, or children playing and arguing on the sidewalks.

In 1947-48, he created a series, some of his best-known work, among immigrants coming from Europe after the war. In one image, two girls are talking by a stack of trunks. In another, an elderly man and woman stand close to each other, his arm around her shoulders as he gestures toward the dock.

Clemens was trying to understand his own immigration through them, he told Cornelia years later. He was drawn to keep coming back to the wharf.

Kalischer photographed the Marlboro Music Festival many times from the 1950s into the 21st century. In 1956, he captured this image of James Levine and Van Cliburn working on a piano duet. Copyright 2017 Clemens Kalischer/courtesy Image Photo

One day as he stood there, he quietly photographed another man with a camera -- the internationally known photographer and photojournalist Henri Cartier-Bresson.

They spoke in New York, and more than 50 years later they met again in Paris, Tanya and Cornelia said. Their father admired Cartier-Bresson, who wrote of his own work with the kind of intuition and spontaneity Clemens would become known for.

Both felt a photographer should blend into the scene to capture people in motion and strong moments of feeling. Cartier-Bresson said that photography puts the head, the eye and the heart “on the same line of sight.”

Settling in New England

Kalischer left New York for Stockbridge in 1951. He wanted to live in the country, his daughters said, but close enough to New York and Boston to keep in touch.

He had begun traveling to Vermont already for assignments and for his own work. His daughters sometimes came with him, and they remember how much time he would spend on his photographs.

Marlboro Music Festival was founded in the same year, bringing young music students and well-known musicians together at Marlboro College, and he might spend a week there, becoming part of the scene. He would see the musicians playing together casually or sitting one-on-one with their instructors, getting into food fights in the dining halls and practicing on the grounds.

In Vermont he would wander too, and he would get to know people and let them become familiar with him.

“He created lifetime friendships with people he photographed,” Tanya said.

He might travel with a camper and park it on side roads, or he might stay with a local family, as he stayed with Sue Stanley and her family on their dairy farm for a Vermont Life feature on “a farm wife.”

He had an affinity for cows and a deep respect for farm life, Cornelia said. Later he helped to develop the model for Indian Line Farm in Egremont, the first farm in the nation to be organized under the concept of community-supported agriculture.

Lens as a compass

Although the Bennington show focuses mainly on freelance work, Clemens photographed many projects on his own, just for the love of it. He would follow an idea the way he might follow a back road just to see where it led, Tanya said.

In the Cantz book, Kalischer says he always photographed for himself, and sometimes an assignment came out of it: “The things that I do for myself usually come out best, and they end up being used sometime.”

The greatest force in his life, he says, has been to remain independent.

“He has been an explorer his whole life,” Tanya said.

“An adventurer,” Cornelia agreed.

“And he has never taken a day off,” Tanya added.

They remember watching as children as he spent hours every evening in his darkroom, developing prints. He might make more than a dozen prints of a single image.

“It was part of his art,” Tanya said. “The process of how he printed is second to none.”

He was meticulous, Cornelia said, about light and shadow, clarity and brightness and contrast.

They remember him talking with editors and looking over images. Freelance assignments might take him to Europe – or to India or Israel. In the Berkshires, he might meet blues, jazz and gospel greats like John Lee Hooker and Mahalia Jackson at the Music Inn in Lenox or classical musicians at Tanglewood.

“As much as he loved classical music,” Cornelia said, “he loved contemporary music. At Tanglewood, he went to every concert in the contemporary music festival. I brought him last year, and I’ll bring him again this summer.”

She remembers watching him in the catwalk in the Shed as he pointed his lens at the musicians from above, and Tanya remembers coming with him to dance performances and concerts and meet visiting artists and performers.

He met artists and performers through Vermont too. “Between Past and Present” includes images from the Flaherty Film Seminar in 1956, from a newly built Modernist dorm at Bennington College in 1968 and from a 1958 Vermont Life photo essay on the town of Peacham, Vt.

Franklin said the image of a dragon’s head in a station wagon comes from Bread and Puppet -- a group of performers founded in the early 1960s by the German sculptor, dancer and baker Peter Schumann, who brought together sourdough loaves and theater with an activist bent, feeding the mind and the body together.

A sense of activism

As he valued the communities he visited in Vermont, Clemens stayed involved in his own community, Tanya and Cornelia said. In Stockbridge he worked with the Laurel Hill Association, a local beautification society that maintains the popular local trail to Ice Glen, and with a range of other area environmental, agricultural and artistic organizations, including the Millay artist colony just across the state line in Austerlitz, N.Y.

For some years he taught photography at Berkshire Community College and at Williams College.

Kalischer opened Image Gallery in 1965 to help and promote emerging artists. He showed contemporary work by many artists who have since become well-known, including Berkshire sculptor Joe Wheaton; Jarvis Rockwell, the son of Norman Rockwell; and the abstract painter Pat Adams, who had a show of work at the Bennington Museum in June.

His gallery still lives in the same 1884 brick building that once served as the town hall. His daughters said he loved modern architecture as well as New England barns, old mills, and doorways around the world. He came back often to the crux between traditional and new.

He was often drawn to Italy, Cornelia said. She went with him later in his life, and she could understand its attraction for him, its combination of age-old buildings with modern glass.

“They take care of their buildings,” he told her.

He photographed landscapes and played with color and abstraction, Tanya and Cornelia said. But over and again they come back, as he has done, to people: Men, women and children move dynamically in his images, part of a game or an embrace or a moment of holding on.

“You feel as though you’re right there with them,” Cornelia said.

Clemens also became a member of One By One, an international organization that describes itself as a meeting place for “the descendants of those who endured and survived the atrocities of the Nazi Regime … (and) the descendants of the perpetrators and bystanders from one of the most evil chapters in human history.”

One by One reconnected him to Germany, Tanya said. He returned several times to talk with children there about current conflicts, not to dwell on the past but to look through his own experience into the present.

At 96, Kalischer rides in a car with his daughters on the back roads with an unobtrusive camera, and he still comes to his Stockbridge gallery often. The gallery shows his own work now, and has for the past six or seven years, and either Kalischer or a member of his family is there regularly to welcome visitors.

The moments of life he has gathered over the last 60 or 70 years fill the walls and overflow. Tobacco farmers are playing the fiddle in the rural South. On a European street, a small girl is running past an open doorway, caught in action in the frame; Clemens loves this picture.

He would agree with Cartier-Bresson that seizing an image is a grand physical and intellectual joy.

“Working was not working, for him,” Cornelia said.

She paused and added, as Henri Cartier-Bresson has also said, that photography is a way of life.

“Between Past and Future: Clemens Kalischer’s Vermont” remains on view through Sept. 4 at the Bennington Museum, at 75 Main St. in Bennington. The museum is open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily throughout the summer. For more information, visit benningtonmuseum.org or call (802) 447-1571.

Image Gallery, at 34 Main St. in Stockbridge, shows Kalischer’s prints. It is open daily, but it’s best to call ahead – (413) 298-5500 – or e-mail inform@bcn.net to check hours or make an appointment. The gallery is launching a Web site, clemenskalischer.com.