Arts & Culture April 2016

From war to circuses, poems of vivid imagery

Pulitzer Prize winner Charles Simic to read at Bennington College

By KATE ABBOTT

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

NORTH BENNINGTON, Vt.

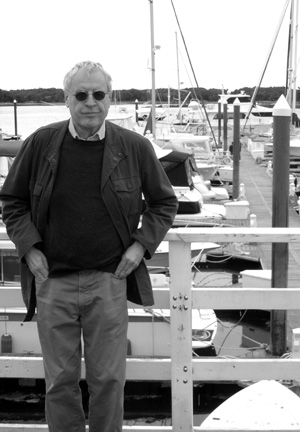

Charles Simic, a former national poet laureate whose work is known for its vivid images and moods that range from intense sadness to comedy, will read his works May 11 at Bennington College. © Philip Simic

Dark leaves swell

against the fading daylight.

A man drops his glasses and staggers away, singing -- or straps on an accordion to leap a waterfall.

The poems come in vivid scenes, often condensed, in a city street almost empty in the small hours, or at a picnic table off a New Hampshire back road in the summer dusk, swept all at once in sadness.

And they will come here on a warm spring night: Charles Simic will read his poetry Wednesday, May 11, at Bennington College.

A former poet laureate of the United States, winner of the Pulitzer Prize and finalist for the National Book Award, Simic has published more than 60 books, including 20 volumes of poetry as well as translations and essays.

He has been known since his first collection, “What the Grass Says,” published in 1967, and for his sense of comedy and intense sadness. In his hands, ordinary objects become so distinct they stand out as curiosities -- a shoe brush, a silver wig, a jeweler’s lens. He blends impressions from his own life, moods and settings, with blood and pageantry -- with big tops, midways and insomniac horses.

In his 2015 collection, “The Lunatic,” a poem called “What the Old Lady Told Me,” begins:

He sawed my head off every night

and twice a week for a matinee.

Magic and spectacle run through the book.

“I always liked circuses and sideshows,” Simic said in a phone interview from his home in New Hampshire. When he was a boy growing up in Belgrade, he recalled, a circus would come once or twice a year and set up near the church.

A church and a circus make the kind of connection that often surfaces in his poems, an independent irreverence he learned firsthand. He grew up in World War II in what was Yugoslavia then, Serbia today.

“We were occupied, bombed,” he said. “The world outside was as dangerous as you can imagine.”

People who were deeply depressed made jokes and laughed together. After the war, his mother was held in a Communist prison with a group of other women, and later she would tell him incredibly funny stories about it.

“She was happy to be released,” he said. “But she would think about those times with a smile on her face.”

Surreal, sensory images

When Simic was a child, his father was exiled, and the family was forcibly separated for more than 10 years, he writes in essays in his 2015 collection, “The Life of Images.”

When he was 15, in 1954, his mother brought the family to the United States; they reunited with his father in New York City and then moved to Chicago. His parents separated. He was working at the Chicago Sun-Times and taking night classes, and he found poetry in books and conversations.

“You take from everyone you read,” he said, and he read avidly: Hart Crane, Wallace Stevens, Emily Dickinson.

He also read the late 19th-century and early 20th-century French poets Baudelaire, Rimbaud and Mallarme, with their sleepless nights and scenes half real, half drunk or dreaming. For a year in high school in Paris, when his family was on the move, he had to memorize them in French. Later he grasped the strength of their influence on his surreal and sensory images.

After Chicago, Simic returned to New York City, collecting old blues records, reading at open mics and beginning to publish. He got drafted into the Army and graduated from New York University. And he became a professor at the University of New Hampshire, where he taught for more than 30 years.

His poems invoke these places like snapshots.

“You walk around with eyes open in New York City or in a small village in New England and look at the people, look at everything,” he said: the houses, the broken-down cars, the shop windows, the woods. Then look again.

“All poetry is about attentiveness,” agreed Mark Wunderlich, director of the Poetry at Bennington program, a series of short-term poet residencies at Bennington College.

Wunderlich, an award-winning poet himself, curates the college’s annual series of readings. He said he first read Charles Simic’s poetry and essays as a college student. He remembers reading “The World Doesn’t End,” a collection of prose poems, not long after it won the Pulitzer in 1989, and “Dime Store Alchemy: The Art of Joseph Cornell,” when it came out in 1992.

Together they gave him a sense of Simic’s poems as collages. Cornell was celebrated for his shadow boxes, sometimes surreal collections of objects. Simic too assembles objects and images in small spaces, and Wunderlich finds humor and great delicacy in the way he brings them together. The connections can seem tenuous, he said, and yet the whole makes sense.

“If you’re involved in the experience of the poem, you believe it,” he said.

The experience of reading becomes immediate – and moving.

Accessible art

“People have a view that contemporary poets are obscure,” Simic said. “In my experience, in readings and interviews, people get poems.”

He hopes for readers who have open minds and who look at a poem with engaging surprise, and he said he finds these readers in many different places. He remembers in a New York City bookstore watching people browse in a poetry section, pull a book off the shelf, open it and page through -- find a poem here, turn a few more pages and get drawn in again.

Wunderlich said he too has found people around him making poetry a necessary and daily part of their lives.

“It’s one of the main interests our students have,” he said.

They want to live with poetry as simply as poets want to write it -- and with as little need to explain why.

Poets are often asked why they write, Simic said, as though they need a reason.

“You write because it’s your instrument -- because you never quite get it right,” he said. “You have an idea, and in terms of yourself there is always a little flaw. You’re striving for that in your own eyes, that perfection, to get it right.”

From a chance beginning, a few words, a few images, a poem will form and find its subject.

“Most poets have no idea where a poem is coming from,” he said. “That’s what makes it so difficult. You start something without knowing what it’s going to be.”

If he knew the message of a poem going in, Simic said, he would not need to write it. A poem will twist, change and take off unexpectedly.

He wants to work with images that surprise and contradictory impulses that do not need to resolve,

Wunderlich said Simic works with images that surprise and contradictory impulses that do not need to resolve. He is inventing a different kind of world, one that reveals “a strangeness, an absurdity in the things we have to endure” in this one, Wunderlich said. Simic’s work can be intensely funny and at the same time make a gesture toward a larger darkness and mystery. Many poets use poems to make sense of the world, but Simic uses poems to show the world does not make sense.

“All of his poems enlarge human experience, what it means to be alive,” Wunderlich said.

The poems show a world capable of anguish or tenderness, “a mixed bag of misery and laughter,” as Simic writes in “The Lunatic.” They show contradictions. And sometimes they focus on compassion and pain when others might want to skim past.

“One question I have never been asked,” Simic said, thinking it over. “I have a lot of poems about homeless people. … We used to call them bums, winos, derelicts.”

No one ever asks about them, he said. When he came to New York City in 1954, to the Village and the East Side, and saw them all the time, sleeping in doorways, he was shocked. It has moved him all his life profoundly, he said, to walk in the city late at night, on cold nights, January nights, and see men and women bundled in rags and newspapers.

They were called “displaced persons” then — immigrants, refugees. That kind of destiny, someone ending up like that, is something he said he feels more compassion for after his family’s experience leaving Yugoslavia.

“You never forget that,” he said. “Seeing someone on a cold night.”

Charles Simic, a former national poet laureate, will read his work at 7 p.m. Wednesday, May 11, at Bennington College’s Tishman Hall. The reading is free and open to all. For more information, visit http://literature.bennington.edu/readings/literature-evenings.