Arts & Culture November 2015

From high society to trench warfare

Book puts new light on Edith Wharton’s World War I dispatches

By KATE ABBOTT

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

LENOX, Mass.

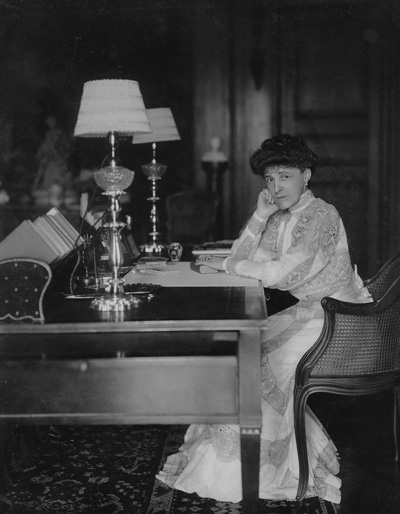

Edith Wharton, seen right at The Mount in 1905, had left the Berkshires to live full-time in Paris by the time World War I broke out. Her accounts from the war’s front lines are collected in a new book. Courtesy Edith Wharton Restoration

The tunnel cut into the hill was wholly dark except for “an occasional narrow slit screened by branches.”

The gunners had screens behind them, to keep any betraying light from showing where they sat with guns between their knees.

Coming out into a “gutted house among fruit trees,” a woman in her 50s looked over a broken wall at another group of helmeted men. She was standing in the farthest outpost of the French trenches, within range of the German guns.

“The artillery had ceased, and the air was full of summer murmurs,” she wrote, later adding, “I could not understand where we were or what it was about or why a shell from the enemy post did not annihilate us.”

This is not the way most people imagine Edith Wharton -- the novelist of high-society New York -- walking in the trenches in World War I.

“She’s a more interesting figure than most people think,” said Alice Kelly, a Women in the Humanities postdoctoral writing fellow at The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities, who has set out to bring Wharton’s war writing out of an obscurity she feels it does not deserve.

A hundred years ago, in the fall of 1915, German and French troops were dug into fortified trenches across more than 400 miles of northwestern France. It was in this year that both sides had used poison gas for the first time and sent foot soldiers against heavy artillery — finding new ways to kill thousands of men at once. By December 1915, more than half a million French soldiers had died.

Wharton made six expeditions to the front lines between August 1914 and August 1915.

Foreign correspondents were rigorously excluded, but she came within sight of snipers, stood beside a sentry looking out into No Man’s Land, and visited hospitals, encampments, “settlements saturated and reeking with wet.”

Wharton wrote about her travels in a series of articles for Scribner’s Magazine and later gathered them into a book. Very few people have read them, however.

Kelly aims to change that and has edited a new critical edition of Wharton’s “Fighting France: From Dunkerque to Belfort,” due out in December from Edinburgh University Press.

The book comes at a time with historical resonances, a century after Wharton wrote her essays -- and at a significant point for her legacy in the Berkshires. This fall The Mount, Wharton’s historic estate in Lenox, cleared its debts: The museum, which came near foreclosure in 2008, has reinvented itself as a cultural center so successfully that in seven years it has paid back $8.5 million.

Berkshires to Paris

At the beginning of World War I, Wharton was still recovering from having sold The Mount. She designed the estate in 1902, and her life had changed here, as it was about to change again. It was at The Mount that she became a novelist.

“She accomplished so much here,” said Anne Schuyler, the museum’s house manager and tour coordinator, “launching her literary career, discovering the ‘republic of letters,’ all these creative minds she so much admired.”

Wharton described reading Walt Whitman on the terrace and talking with friends, immersed in “the richest and most varied mental companionship” of a kind she had never had. She went for long drives in the car she named George after George Sand, the famous French novelist, who was also a woman.

“The Mount was my first real home and ... its blessed influence still lives in me,” she wrote in her memoir, “A Backward Glance.”

Wharton published “The House of Mirth,” the novel that won her international fame, in 1905, when she was 43. Like many of her works, it was set among, and critical of, the New York elite into which she was born.

“My recognition as a writer had transformed my life,” she wrote in her memoir, describing herself for the first time as fully alive and at home.

“Life in the country is the only state which has always completely satisfied me,” she wrote, adding, “Now I was to know the joys of six or seven months a year among woods and fields of my own.”

The other half of each year she began to spend in Paris. So as she took root in the Berkshires, she also took root in France, and when she lost her footing in Lenox, she turned to Paris to find it again.

The Whartons left The Mount finally in 1911, as Teddy Wharton became increasingly mentally unstable. Edith wrote “Ethan Frome” the same year, and she divorced Teddy in 1913, setting off a period of manic energy, Schuyler said. She was traveling constantly, full of restless vigor and indecision.

And then, in 1914, at an Edwardian garden party, she learned of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s assassination. She describes returning home in her first essay in “Fighting France”:

“It was sunset when we reached the gates of Paris. Under the heights of St. Cloud and Suresnes the reaches of the Seine trembled with the stillness of a holiday evening. ... The next day the air was thundery with rumors.”

Privilege amid wartime

Within days, the city had mobilized. Troops were called out, taxis were commandeered, shops were closing, and tourists were stranded. Paris was becoming paralyzed and silent. Nothing was moving. Houses and hotels were turning into Red Cross hospitals.

Wharton loved Paris, so she set out to do what she could.

More war correspondents would come later, some of them women, including Arlington, Vt., novelist Dorothy Canfield Fisher, said Alan Price of Great Barrington, a professor emeritus of English and American studies at Pennsylvania State University and author of “The End of the Age of Innocence: Edith Wharton in the First World War.”

But Wharton was one of the first. People knew her name around the world, and she used it. Few people could travel freely in France then; few people had cars, and sentries asked for passports at every crossroads. But Wharton came within sight of the French assault at Vauquois.

“She could do more than people could do later,” Kelly said. “The laws about travel had not quite settled down. She was taken on certain routes and allowed more liberty.”

Wharton traveled with her friend Walter Berry (who would become president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Paris) and with her chauffeur, Charles Cook, and a maid.

Price said there was a kind of spectacle in Wharton, in her fashionable clothes and her unrequisitioned car, driving country roads with the signs missing and pulling into towns full of military vehicles where she couldn’t find room at the inn.

“The juxtaposition was not lost on French satirists,” he said.

The Mount displays a 1916 cartoon of her in its exhibit on Wharton and the war. She could laugh at the image, he said.

But because this kind of mockery has followed her, her war writing is rarely taken seriously, Kelly said.

In a talk at The Mount in August, Kelly suggested that some readers feel uneasy at Wharton’s tone, as she shifts from broken men and broken buildings to idealized glimpses of jolly camps and high-hearted soldiers, “the men who made the war and the men who were made by it.”

“She’s guilty of that -- she’s excited by war,” Kelly agreed in a recent phone interview.

Wharton wrote with palpable patriotism, and she was not alone.

“People believed this war was fighting to save civilization,” and that soldiers “were dying to save France,” Kelly said.

Grappling with war’s toll

But when Wharton talks about “a long line of éclopés -- the unwounded but battered, shattered, frostbitten, deafened and half-paralyzed wreckage of that awful struggle,” she gives a sense of shell shock, Kelly said.

At a hospital in Verdun, Wharton wrote, “the wounded are brought in encrusted with frozen mud, and usually without having washed or changed for weeks.”

And in a village turned into a colony of 1,500 sick and exhausted éclopés, Wharton went into the church.

“In the doorway our passage was obstructed by a mountain of damp straw which a gang of hostler-soldiers were pitchforking out of the aisles,” she wrote. “The interior of the church was dim and suffocating. Between the pillars hung screens of plaited straw, forming little enclosures in each of which about a dozen sick men lay on more straw, without mattresses or blankets.”

Kelly said Wharton was writing against the backdrop of terrible loss.

“She’s trying to process what’s going on,” Kelly said. “She called it being ‘pen-tied.’

“Everyone would have lost someone -- a husband, a brother,” Kelly said.

Though Wharton was passionately patriotic and pro-war, “she was aware of the harsh realities of war -- she’s not glossing over what war means,” she added. “In my book, I called it an uncomfortable propaganda. The more I read and footnoted, the more I found classical allusions, an enormous depth of knowledge. And these were written in wartime, while the war was ongoing. She dashed these off at some speed.”

Wharton also wrote these essays with a purpose. By February 1915, when she began them, she was overseeing a massive network of organizations helping people displaced by the war -- an ouvoir (work room) for women out of work, and schools and shelters for Belgian refugees, children and pensioners and women and children suffering from tuberculosis.

She had become, as Schuyler put it, “a CEO” of these relief efforts.

Wharton became an entrepreneur, a manager and a formidable fund-raiser for her causes. In 1915 she also published “The Book of the Homeless,” an anthology of writing and artwork from well-known artists, to benefit her war work, and she held musical soirées with musicians and composers who’d been left out of work in the conflict.

“She raised millions, all told, in today’s money,” said Price, the Great Barrington professor.

Her writing took on an element of public relations for her programs and for her adopted country.

“In a letter to her sister-in-law, Mary Cadwallader Jones, she consigns president Woodrow Wilson to one of the circles of hell” for keeping America out of the war, he said. “She could not come out and say this about neutrality and Americans and German Americans in public, because she was depending on the goodwill of her neighbors in the U.S. to support France and her charities.”

But more than any executive decision, Kelly, Price and Schuyler said, the “Fighting France” essays were moved by the dislocation and the strangeness of war, the loss of her servants and friends and the weight of observing these changes.

“She saw civilization crumbling,” Schuyler said. “She makes ruins of a cathedral more eloquent than human misery -- what a waste, this great beauty man has created and is destroying. It has an absurdist unreality, like M.A.S.H. ... It was a devastating, all-encompassing experience. She suffered health issues and crises of the heart.”

Wharton wrote to a friend who had lost a son at the front that the only refuge was work. And so she turned to writing for solace and a fragment of order in a chaotic world.

“She has an eye for telling detail,” Schuyler said. “She will metaphorically walk you into a room and with a few sketchy sentences you’d know the character of the person” who lives there.

“I enjoy her travel writing for the same reason -- you know what that devastated cathedral looks like, feels like, the meaning of it,” she added.

Kelly likewise said Wharton’s clear images stick in the mind -- and keep coming back.

“Next time I go to Paris,” she said, “I won’t be able to walk around without seeing” the scenes Wharton described -- “boats on the Seine and hotels made into hospitals.”