News & Issues June 2015

The Einstein of Glens Falls

Local man’s memoir details ties to famous physicist but draws questions

By STACEY MORRIS

By STACEY MORRIS

Contributing writer

GLENS FALLS, N.Y.

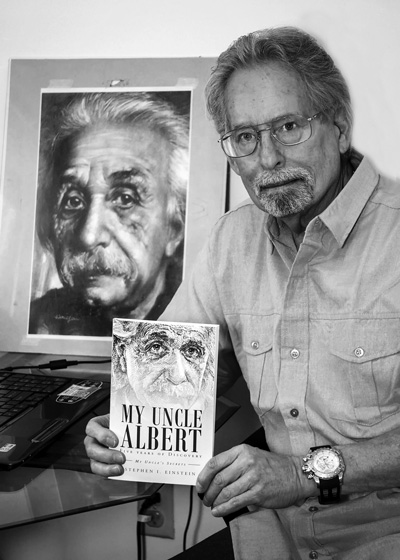

Stephen Einstein’s book “My Uncle Albert” describes the five boyhood summers he says he spent with Albert Einstein

Joan K. Lentini photo

It’s late afternoon, and Stephen Einstein has just arrived at a downtown diner at an off-peak hour, which turns out to be a good thing.

He’s there to discuss, in abbreviated form, the details of a life so filled with unusual details that even he is amazed sometimes at the plot twists.

Einstein opens a menu as his crystal-blue eyes do a quick scan.

“I just want to make one thing clear,” he says, leaning across the table for emphasis. “If it weren’t for Albert Einstein, I wouldn’t be sitting here now. … I’d be dead.”

It’s a dramatic statement perhaps, but the 70-year-old Glens Falls resident says the most famous physicist in history was more than just a storied figure to him. He was an uncle.

Last year, at the urging of some close friends, Stephen wrote a memoir describing the five childhood summers he says he spent with Albert Einstein in the early 1950s. The result is a 120-page book, “My Uncle Albert: Five Years of Discovery,” printed by Page Publishing of New York City and available for sale on Amazon.

Stephen Einstein and his supporters say his late father, Alfred Einstein, who once owned a popular restaurant on Route 9 south of Lake George, actually was a half-brother of Albert Einstein. Alfred, they say, was born of an extramarital affair involving the physicist’s father, Hermann Einstein, in Italy around the turn of the 20th century. (Hermann Einstein lived in Italy from 1894 until his death in 1902.)

In the preface to his book, Stephen describes himself as Albert Einstein’s “last blood relative on this planet.”

But the physicist actually has five great-grandchildren who are alive and well, two of whom disputed Stephen’s connection to the family when contacted.

“I don’t know who Stephen I. Einstein is,” said Thomas Einstein, an anesthesiologist in southern California who was born in 1955, the year Albert Einstein died. “From the knowledge of my family tree, there is no blood-related nephew.”

A traumatic childhood

In his book and in person, Stephen Einstein describes the first few years of his life as opulent and carefree, thanks to a financially savvy father who made his living as a corporate raider – and also, Stephen says, as a money launderer for organized crime.

“I grew up in a Long Island mansion surrounded by wealth,” he recalled.

That all changed on a dime in 1949 when his father abandoned the family and disappeared to Florida for a year.

Stephen recalled how the abrupt departure left him and his mother broke. They moved to a small apartment in Queens and survived on the modest income from his mother’s secretarial job.

Then, on a quiet Sunday evening when he was nearly 5, Stephen says his father arranged for his only son to be kidnapped and brought to upstate New York, where Alfred Einstein had established a new home.

Stephen describes the next 13 years as a blur of physical and mental abuse at the hands of his father and new stepmother.

“My father was a monster a lot of the time, and he did terrible things,” Stephen recalled. “But he was bipolar and didn’t take his medicine, which he should have.”

It was this unmedicated state that Stephen says led to his father’s mood swings and rages. But he said there were moments of calm and lucidity, like the day Alfred summoned his son for a sit-down to announce he had a very famous half-brother who was known around the world for his accomplishments in the world of physics and as a humanist.

“My father always hated my uncle, and I never understood why,” Einstein recalled. “But he told me that day he wanted me to spend time with him and get to know this amazing man.”

Summer escapes

So in 1950, he says, began a routine of Stephen being driven by the family chauffeur to Princeton, N.J., to spend summers with his Uncle Albert.

Unlike the volatile Alfred, Stephen recalls Albert Einstein as gentle, doting, and unfailingly hospitable.

“He was a great cook,” Stephen said with a smile. “Uncle Albert’s Sunday breakfast always was a big spread of sausage, bacon, ham and eggs. And my uncle always made sure there was a cold glass of milk for me in the refrigerator.”

His memoir describes how, for the five years before Albert’s death in 1955, uncle and nephew bonded over the simple and the sublime. Stephen recalls his uncle, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics in 1921, as a quiet, gentle man who loved nothing more than spending contemplative time with his young nephew at his property’s duck pond.

By the 1950s, according to Stephen’s memoir, Albert Einstein was in his 70s and seemed to relish simple things like quiet walks and picnic lunches. In these unhurried encounters, he says, the conversation meandered from ducks to philosophy to Albert’s take on the possibility of extraterrestrial life.

“My uncle was a very private man, but he saw something in me that encouraged him to tell some of his deepest, darkest secrets,” Stephen said. “He said I was the only one he could cry in front of.”

Stephen said his Uncle Albert was also very open with him about his regrets – confiding, for example, that he felt he had been a bad father.

“He regretted being a womanizer and cheating on his wives,” Stephen said.

Fact or fiction

But did these idyllic childhood summers really unfold as Stephen Einstein says?

Ted Einstein, a great-grandson of Albert Einstein who runs a high-end furniture business in Los Angeles, strongly disputed Stephen’s account after reading a preview of his book on Amazon. He said he doesn’t know of Stephen Einstein and doesn’t believe he’s connected to Albert Einstein’s family.

And Thomas Einstein, the anesthesiologist and Ted’s older brother, suggested some details of Stephen’s account might have been inspired by the stories of their father, Bernhard Einstein, who died in 2008. Bernhard Einstein spent his boyhood summers with Albert Einstein in the 1930s in New Jersey and in the Adirondacks at Saranac Lake, and he described these experiences in media interviews later in life.

“My father did spend summers with his grandfather, Albert Einstein,” Thomas said. “Perhaps this is where these recollections of Stephen originate.”

Stephen Einstein said the completion of his book is largely the result of encouragement from his mentor and longtime friend, Sid Gordon of Saratoga Springs.

“I kept telling Stephen he was foolish to sit on a great story like this,” Gordon said. “There are a lot of books on Albert Einstein, but they all say basically the same thing. Stephen’s book is a one-of-a-kind because it gives a picture of the legend from a child’s point of view.”

Stephen Einstein said he waited until later in life to tell his story to avoid hurting any relatives who might be upset by the book’s portrayal of his father and others.

“I waited a long time to write this book, because my family were all still alive and I didn’t want to disrespect them,” he explained.

When told that Thomas and Ted Einstein had disputed his claim of a connection to their family, Stephen responded obliquely.

“There was a lot of love-hate in my family,” he said. “When my father died, that was it, everything was severed. Everything. I had many reasons for doing it, not one or two. … All ties were cut in my early 20s, and I’d do it again if I had the chance. But the love of my Uncle Albert continues in my heart. I wished he would have been my father.”

Stephen said he wrote “My Uncle Albert” to show the world that his uncle was a humble man who never let fame go to his head. And writing the book was in some ways a means to revisit some of the happiest times in his life, he said.

“Uncle Albert was a gentle person who detested violence,” he said. “He wanted to help humanity. And during those years we spent together, he wanted to leave me something I could use later in life.”