News& Issues February-March 2015

In Bennington, a battle over fluoride

Doctors see public-health benefit, but opponents decry ‘mass medication’

By EVAN LAWRENCE

By EVAN LAWRENCE

Contributing writer

BENNINGTON, Vt.

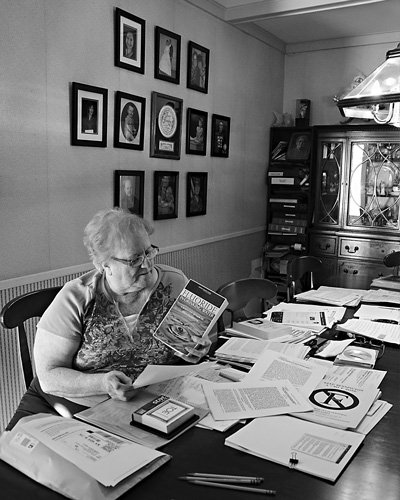

Mary Lou Albert is one of the organizers of Bennington Citizens Against Fluoridated Water, a group opposing a March 3 advisory vote on whether to add fluoride to the town’s drinking water. The measure is supported a group of local health care professionals, the Bennington Oral Health Coalition.

The proponents say they have science and statistics on their side.

Consider:

• More than 50 percent of kindergarten and third-grade students screened in two of Bennington’s elementary schools have cavities, according to a recent state survey.

• Fluoridation of a municipal water supply reduces cavities in adults and children by between 20 percent and 40 percent, according to the American Dental Association.

• Every $1 spent on fluoridation saves an average of $38 in future dental treatments, again according to the dental association.

Those numbers are why the Bennington Oral Health Coalition, a group of local health professionals and concerned citizens, has asked for an advisory vote at the March 3 town meeting on whether Bennington should add fluoride to its drinking water.

When it comes to dental care for Bennington residents, “clearly whatever we have now isn’t working,” said Dr. Richard Dundas, medical director of the Bennington Free Clinic and a member of the coalition. “We think we have the science strongly behind us.”

But Bennington has a long history of resistance to fluoridated water. The issue has come before the town five times previously -- the first time in 1963, and most recently in 2002. Each time, opponents blocked it.

“I like freedom of choice, not mass medication,” said Mike Bethel, a local activist and frequent critic of the town government. “A lot of evidence says this is not good.”

Bethel and other opponents have formed their own group, Bennington Citizens Against Fluoridated Water, to push back against the town-meeting initiative.

The opponents say they fear overexposure to fluoride could have unintended health consequences for some people, and they argue that it would be better for the town to take other, more targeted steps to promote improved dental care.

Both sides have lately been flooding the local daily paper, the Bennington Banner, with letters supporting their position and casting doubt on the other side’s arguments.

A history of controversy

Fluorine, the elemental form from which fluoride is derived, is a poisonous gas. But the gas is almost unknown in nature.

Fluorine combines readily with other elements, most notably calcium, to form fluorite and other minerals. These compounds are very stable. They occur naturally in soil and water, plants, and animals’ teeth and bones. Crystal enthusiasts prize fluorite’s eight-sided crystals for their beauty and metaphysical properties.

The sodium fluoride in toothpaste -- and in the compounds used to fluoridate water -- is derived from the processing of limestone for fertilizers and building materials. Contrary to some opponents’ claims, the fluoride used in tap water is not industrial waste.

Many studies have demonstrated that drinking water containing about 1 part per million of fluoride reduces tooth decay by strengthening tooth enamel. Fluoridated toothpaste, rinses and dental treatments also help, but supporters cite studies showing the two approaches together work better than either alone.

Grand Rapids, Mich., was the first U.S. city to fluoridate its water supply, in 1945. Today, about 200 million people in the United States and 57 percent of Vermont residents receive fluoride through their municipal water supply.

“This is not New Age,” Dundas said.

Nationally, opponents of fluoridation found themselves at the losing end of a series of court battles as the practice spread in the 1950s and ‘60s. But in communities where the issue has been put on the ballot in recent years, about half have rejected it.

Around the region, communities that fluoridate their drinking water include Rutland, Burlington, Poultney and the New York cities of Saratoga Springs, Troy and Rensselaer.

But some other large municipalities, including Brattleboro and Albany, N.Y., have opted against fluoridation.

Touting public health benefits

The Bennington Oral Health Coalition grew out of a series of community meetings that the state Commission on Rural Development held in Bennington in 2012. The coalition has standing as an official town committee. It receives no town funds, but it has been supported by about $5,000 a year from Greater Bennington Interfaith Community Services, coalition member Sue Andrews said.

One of the concerns identified in the 2012 discussions was the poor oral health of many residents, especially children. The push for fluoridation was spurred by a report released in September by the state Health Department’s Office of Oral Health. In 2013 and 2014, the department’s researchers examined the teeth of kindergarten and third-grade students at 24 public schools around Vermont. Some schools had fluoridated water; some did not.

Two Bennington schools, Bennington Elementary and Molly Stark, were included in the study. Both schools had among the highest rates in the state of children with cavities.

Michael Brady, a dentist who treats low-income children ages 2-10 through a state program at Molly Stark School, said more than 140 of his patients last year required hospital treatment under general anesthesia for their decayed teeth.

The children “need better diets, better home health habits, and fluoride products,” he said. “Water fluoridation is the easiest and most effective way to get fluoride to them.”

Andrews, the staff coordinator of the Bennington Free Clinic, said the benefits of fluoridation should make voters’ decision clear.

“This is about community values,” Andrews said. “Do we want to be the community where 58 percent of our kindergarteners and third-graders have cavities?”

She added that children with tooth decay miss school, can’t eat, and have headaches. By their 20s, they can start losing their permanent teeth.

“It’s not normal to lose teeth,” she said. “You should have your teeth until you die.”

Many on the pro-fluoridation side see the claims of opponents as little more than fear mongering.

“We think we have the science strongly behind us,” Dundas said. “We have a list of 40 things opponents claim fluoride does with no basis in fact.”

Hundreds of properly designed, peer-reviewed studies over the last 70 years have shown that water fluoridated to recommended levels is safe and effective, he said. The federal Centers for Disease Control lists fluoridation as ninth on the list of top 10 public health achievements of the 20th century.

Unintended risks?

But opponents see fluoride as a poison. Fluorine compounds used in industry are indeed toxic, although water treated with the recommended concentration 1 ppm of fluoride is far below the level considered toxic.

In a letter to the Banner, Dundas pointed out that to ingest 5,000 milligrams of fluoride, the amount the American Dental Association considers toxic, one would have to drink about 1,300 gallons of fluoridated water at one sitting.

But opponents point to the drinking water standards set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which recommends fluoride not exceed 4 ppm in water for a lifetime of consumption.

The EPA says long-term consumption of fluoride above that level may lead to increased likelihood of bone fractures in adults and may result in effects on bone leading to pain and tenderness. Children under 8 exposed to excessive amounts of fluoride also have an increased chance of developing pits in the tooth enamel, according to the agency.

Mary Lou Albert, one of the organizers of Bennington Citizens Against Fluoridated Water, said she objects to fluoridation in part because “fluoride isn’t a nutrient.”

“Nothing will happen if you never get it,” she said.

Dundas conceded that point.

“It’s not essential, but it’s helpful,” he said.

Despite the many studies supporting fluoridation, opponents point to a handful of studies that they claim have been overlooked or suppressed by government and the medical establishment suggesting that fluoridation is ineffective or even harmful.

Albert also cites her own experience. When her first three children were born, her family was living on Long Island and drinking well water. On the advice of her pediatrician, she gave them fluoride supplements. Their baby teeth and permanent teeth were slow to erupt and irregular, requiring oral surgery to correct them.

Albert’s fourth child was born in Bennington. She didn’t give the child fluoride, and that child’s teeth came in normally. She did some research on the Internet and concluded on her own that fluoride supplements were the culprit behind her first three children’s dental problems.

Dundas, however, countered that a recent study of more than 13,000 children looked at just that question and found that fluoride had no effect on tooth eruption.

Debating the details

Fluoride opponents also object to what they consider forced medication.

“Fluoridation takes away our right to choose,” Albert said.

Bethel pointed out that people who believe fluoride would help their families’ dental health already have the option of buying toothpaste and other products that include fluoride.

“You can get fluoride products yourself if you want them,” Bethel said. “We don’t want it and don’t want the general public to have it.”

Dundas countered that fluoride is a naturally occurring substance, not a drug or medication. (The town’s water already contains 0.1 ppm of fluoride.)

“I can sympathize with the desire not to be forced, but this is for the greater good,” he said.

Opponents say they would rather see more programs to teach people about good dental care and to give them toothbrushes and toothpaste, plus expansion of dental care for low-income people.

Fluoride supporters say those things would be good but expensive. The cost to local and state taxpayers last year for treating dental emergencies among low-income residents “was many times what would be spent on fluoridating the town’s water,” Andrews said.

The American Dental Association says community costs to fluoridate public drinking water range from 50 cents to $3 per person per year, depending in part on a community’s size. Andrews estimates that Bennington would spend about 75 cents per person.

Greg Van Houten, the chairman of the Bennington Select Board, said the coalition has collected enough signatures to place an advisory question on the town meeting ballot. The Select Board, which also serves as the town’s water board and board of health, will make the final decision on whether to proceed with fluoridation.

Bennington’s water system serves 3,700 customers, reaching about 13,000 people, said Terry Morse, the town’s water resources superintendent. North Bennington, including Bennington College, has its own water system, as does Southern Vermont College.

Morse said he has contacted other town around the state to start finding out what fluoridation would cost and how to go about it. The details will depend on the chemistry of Bennington’s water, which is very acidic, he said.

Van Houten said state grants might be available to help pay the startup costs.

The Select Board chairman said his personal position on the question has evolved.

“I was originally opposed, but when I looked at the available research, I couldn’t support my position,” Van Houten said. “The substance of the arguments against it falls apart. Every level of government supports it. People balk at the cost, but when you have to send 100 kids to the emergency room to have teeth extracted, we’re already paying.”

Fluoridation also protects adults’ teeth, he added, saving significantly on their dental expenses.

The Bennington Oral Health Coalition will hold a town-sanctioned information meeting on the issue from 6:30 to 8:30 p.m. Thursday, Feb. 12, at the town firehouse at 130 River St.

Bennington Citizens Against Fluoridated Water will hold its own information meeting from 6 to 8 p.m. Thursday, Feb. 19, at the same location.

Town residents will be able cast ballots at the firehouse on town meeting day – Tuesday, March 3 -- or by early and absentee ballots before the meeting. For more information, contact the town clerk at (802) 442-1043.