News December 2015-January 2016

Pride or oppression?

Confederate flag sales at a county fair prompt outcry

By THOMAS DIMOPOULOS

By THOMAS DIMOPOULOS

Contributing writer

GREENWICH, N.Y.

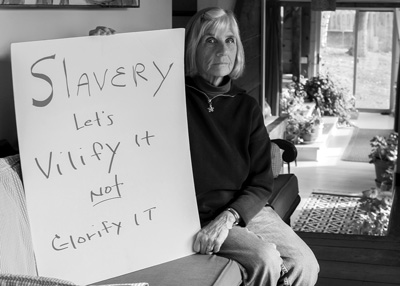

Photo by Joan K. Lentini: Ann Townsend displays a sign she created in August to protest the sale of Confederate flags at the Washington County Fair.

When Ann Townsend saw the Confederate battle flag prominently displayed at some of the vendor booths at the Washington County Fair this summer, she was appalled.

Just two months before the fair, nine black churchgoers had been shot to death in a racially motivated attack in Charleston, S.C. Police identified the young gunman as a white supremacist who, before the shootings, had posted online photos of himself alongside the Confederate flag.

By early July, the Charleston massacre had led to a change that 50 years of efforts by civil rights activists had not achieved: It convinced South Carolina’s governor and legislators to permanently remove the Confederate flag from the grounds of the State House, where it had flown since the early 1960s.

Other states of the old South – including Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, Tennessee and Virginia – soon were debating whether the stars and bars should continue to be flown at government buildings or displayed on license plates. Retailers including Wal-Mart, Amazon, eBay and Sears all announced bans on the sale of Confederate flag merchandise.

Against this background, Townsend said, it seemed doubly shocking to see the flag displayed at the county fair here -- in a region that once was a center of the abolitionist movement.

“When I saw that flag, it just hit me like a knockout punch,” she said. “It was something I feel strongly about, but it always seemed to be so far away. This was right on my doorstep. I’m shy, but I thought: There’s no excuse. Get out there.”

So Townsend created a handmade sign that read, “Slavery: Let’s Vilify It, Not Glorify It,” and headed to the fair, which she had often visited with her children and grandchildren.

“There were a few different booths” with Confederate flag merchandise, she said. “I went over to the first one and just stood there. I was a little nervous, and I didn’t know what to expect. The woman behind the booth came out and said, ‘If you think this has to do with slavery, you don’t know anything about history.’”

Then the fair manager approached her with two police officers and asked her to leave.

“They were polite,” Townsend said. “They explained I could stay outside the fence. So the next day I stood under their sign, outside, for two hours.”

Calls for a ban

Calls for a ban

Now Townsend and others are calling on the board of the Washington County Fair to ban the sale of Confederate flags before next year’s event.

The weeklong agricultural fair attracts about 120,000 people each year and features more than 1,800 exhibitors, nearly 2,000 farm animals and dozens of carnival rides. The fairgrounds cover 120 acres in the town of Easton, just west of Greenwich on Route 29.

Last month, Townsend was one of three people who spoke at a meeting of the fair board and urged its members to forbid the sale of Confederate flags in its vendor manual for the 2016 fair. That manual already forbids the sale of about a dozen types of goods, including alcohol, fireworks, knives and laser pointers. It also forbids the sale of “articles of obscene nature,” and reserves for the fair management the right to determine what is obscene.

“No one would condone swastikas or sexually explicit materials to be displayed or sold at the fair,” Townsend told the board. “To many of us, the Confederate flag is just as reprehensible.”

The fair board didn’t make an immediate decision on the flag issue. The board is made up of 32 volunteer members, including the town supervisors of Easton and Greenwich.

R. Harry Booth, a former Easton supervisor who is chairman of the board, didn’t respond to a phone message requesting comment for this story. But he told other news organizations after last month’s board meeting that Confederate flag issue will be reviewed through the organization’s committee system before the board makes a final decision.

“We certainly don’t want to create any hard feelings or any controversy,” he told Albany-area TV station WTEN.

Vendors have sold the Confederate flag and associated paraphernalia at the Washington County Fair for several years. A Saratoga Springs business that was identified as one of the vendors at this year’s fair did not respond to a request to comment for this story.

Clifford Oliver Mealy, the fair’s official photographer, said the Confederate flag’s presence has always troubled him, but he was particularly bothered this year by what seemed to be a more aggressive display.

“It’s been there in the past, but it was far more discreet,” Mealy said. “This year it really made its prominence. It was after the killing of the nine church people in South Carolina, and after all those states started taking it out of their statehouses.”

Mealy, who is black and is a Vietnam veteran, said the display of the Confederate flag feels to him like a slap in the face, and he urged the fair board to put a stop to future displays and sales.

Abolitionist roots

In decades past, simply displaying the Confederate flag in this region would have been viewed as treasonous.

The Civil War remains America’s bloodiest conflict, with the number of war dead on both sides estimated at more than 600,000. More than 5,000 soldiers from Vermont and nearly 14,000 from Massachusetts were killed in action or died from the effects of the war, according to Frederick Dyer’s book, “A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion.” The death toll of New York soldiers topped 53,000, according to Frederick Phisterer’s “New York in the War of the Rebellion.”

Locally, 169 soldiers from the 123rd Regiment New York Volunteer Infantry, organized in southern Washington County, lost their lives fighting the Confederacy.

In Greenwich, “the most prominent statue in town is of a Civil War veteran,” Mealy said. “The names of the other veterans across the back of it are names you still see on mailboxes in town today.”

Even before the war, Easton and Greenwich, which was then known as Union Village, were hotbeds of abolitionist activity. After New York abolished slavery in 1827, local people provided safe houses for Southern slaves fleeing to freedom in Canada. Some of these local stops on the Underground Railroad are tourist sites today, and several of them are detailed on a historical marker in the center of Greenwich.

In an incident soon after World War I, the display of the Confederate flag at Saratoga Springs’ Convention Hall so incensed local Civil War veterans H.B. Ormsbee and R.S. Rimington that the men risked larceny charges by removing the banner.

“We had just as much right to tear down and burn that flag if we wished as a veteran of the World War would have to destroy a German flag if it were displayed,” Remington told the court, according to a front-page story in The Saratogian newspaper on April 30, 1919.

Heritage or slavery?

The Confederate flag has gone through a variety of incarnations since its first version appeared at the dawn of the Civil War. But it is the version with stars and bars upon a red background, officially the battle flag of northern Virginia, that is best known. That is the version that was carried by members of the Ku Klux Klan as a symbol of white supremacy -- and the one hoisted in opposition to the Civil Rights movement in the 1950s and ‘60s.

More recently, though, the flag’s defenders have cast it as a symbol of Southern regional pride, and some of the vendors displaying it at the fair this year picked up on this theme – such as by offering versions of the flag that bore the words “heritage not hate.”

In popular culture, the flag was identified beginning the 1970s with Southern rock bands like Lynyrd Skynyrd and with the outlaw characters like those in the television show “The Dukes of Hazzard.” In the past few years, however, Lynyrd Skynyrd backed away from its use of Confederate imagery, and this summer Warner Bros., which produced “Dukes of Hazzard,” yanked reruns of the show off the air and ended the production of all show-related merchandise bearing the Confederate flag.

To many people, the flag still represents slavery and oppression.

The competing views of the flag might pose a dilemma for board members of the Washington County Fair. Some might view the flag’s sale and display as a kind of hate speech, but others might view flag displays as an act of freedom of speech.

Mealy said the Confederate flag is historical and as such should have a place in museums. But he said he opposes seeing it widely sold to consumers.

“In Germany it’s illegal to sell the swastika,” Mealy said, adding that the same standard should apply to the Confederate flag here.

“At the same time, I’m a big believer in freedom of speech,” he added. “I wouldn’t be able to be saying this if we didn’t have that freedom. I can see how the board could be in conflict, because it involves freedom of speech. But at the same time, it’s just such a scar.”

Although some might see a fair board decision to ban Confederate flag sales and displays as an impingement on freedom of speech, an official of the New York Civil Liberties Union did not consider the controversy a free-speech issue.

“State, local and county fairs are a chance to celebrate what makes New York so unique – New Yorkers,” said Melanie Trimble, the Capital Region director of the NYCLU. “Fairs that take pride in supporting respect for all New Yorkers are taking an appropriate stand by requesting that vendors not sell the confederate flag, a symbol of oppression and discrimination that hurts many New Yorkers.”

Decision time

The fair board is expected to settle the issue in early 2016.

“I think they have a hard decision to make,” said Al Cormier, the Salem town historian. “Do the people who buy the flag see it as historical symbolism or as an act of defiance to just go out and raise hell in the community?”

Cormier serves as chairman of the 123rd Regiment Civil War Commemorative Committee, a role in which he helped organize a series of events earlier this year in Salem to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War. The 123rd Infantry Regiment, also known as the Washington County Regiment, was organized at Salem.

“There were brave men that fought on both sides,” Cormier said, adding that he was speaking personally and not as a representative of the county. “Unfortunately, the flag seems like it was hijacked to represent white supremacy and the KKK.”

Townsend said she didn’t know how soon the fair board would act but that she hoped it would be before the spring deadline for vendor applications.

She noted that the board had already made its decisions for the 2015 fair before the South Carolina shootings and the backlash against the Confederate flag that followed.

“Last year, everything was already set up,” she said. “I am not faulting the Washington County Fair Board for circumstances they were not able to control at the time. But for next year, now they know.”