News December 2014-January 2015

Labors of love

Region’s colleges turn more to part-timers, creating a second tier of teachers

By TRACY FRISCH

Contributing writer

QUEENSBURY, N.Y.

Neal Herr and Rebecca Cash are among nearly 200 adjunct faculty members at SUNY Adirondack in Queensbury, N.Y. The college has increased its roster of part-time instructors from 154 to 196 in the past 10 years.

Rebecca Cash found her calling in 2009 when she stumbled into a part-time job teaching English composition at her local community college, SUNY Adirondack.

She found the work unusually fulfilling, in part because the school serves many students who are the first in their families to go to college. Helping these students develop their writing skills -- and go on to careers or advanced studies at other colleges -- has its own special rewards, Cash said.

“I just love teaching at the two-year level,” she said.

But after working as an adjunct instructor for five years and completing her second master’s degree, Cash has been unable to advance to a full-time position and is still struggling to piece together a living from teaching.

Cash, 44, currently keeps up an almost impossibly hectic schedule teaching classes at four different institutions – SUNY Adirondack, Empire State College, Schenectady County Community College, and Mildred Elley, a business college in Albany where she picked up a class this year. She also has a fifth job, working up to 11 hours a week as a tutor in a college-funded program.

“I’m going to have to leave teaching if something doesn’t change,” Cash said.

Stories like Cash’s have become common around the region as colleges increasingly turn to part-time instructors to fill out their course schedules. Despite their often-extensive academic credentials, these adjunct faculty members are paid far less than their full-time counterparts, and they typically receive no health insurance or retirement benefits.

They also lack job security: They don’t get paid if they don’t teach, and if not enough students sign up for their classes, adjuncts can be told at the last minute that their services aren’t needed.

At the SUNY Adirondack campus near her home in Queensbury, Cash is one of about 35 adjunct instructors in the English department, which has a full-time faculty of 16. The adjuncts mainly teach the required basic writing courses.

This year, Cash has a total of 120 students at her various colleges – and plenty of papers to read and critique.

“If an English composition teacher isn’t reading papers every week, you’re not doing the job for the students,” she explained.

Low-cost labor pool

SUNY Adirondack, known for most of its existence as Adirondack Community College, changed its name in 2010 to emphasize its ties to the State University of New York system, through which students now can earn four-year degrees at the Queensbury campus. As a result of these changes and the opening of the first-ever student dormitory on campus, enrollment reached a record-breaking 4,200 last year.

But although some retiring teachers have been replaced, the number of full-time faculty at SUNY Adirondack -- 96 – is exactly the same as it was 10 years ago. The college appears to have kept pace with its enrollment growth solely by expanding its roster of adjuncts, whose numbers have increased in the past decade from 154 to 196.

The increasing reliance on adjunct faculty is evident at other colleges around the region and is part of a longstanding national trend. According to the American Association of University Professors, adjuncts and other non-tenure-track instructors, such as graduate students and visiting professors, now account for 76 percent of the teaching staff at U.S. colleges and universities, compared with 55 percent in 1975. Part-timers in particular have grown from 24 percent of instructors nationally in 1975 to 41 percent today.

One reason for the growing number of adjuncts is that their labor is cheap. Nationally, the median annual pay for all post-secondary teachers, including adjuncts, was $68,970 in 2012, according to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics. But at the region’s community colleges, many full-time professors earn less than that, and adjuncts receive a lot less.

At SUNY Adirondack, where the faculty union recently negotiated an increase in the pay scale, adjuncts now receive $2,670 to teach a three-credit course. At that rate, a person teaching four such courses per semester would earn less than $22,000 a year. That’s below the poverty line for a family of four.

And since adjuncts by definition are part-timers, they aren’t allowed to teach a full course load (five three-credit courses at most community colleges) at any one institution. The result is that adjuncts who try to make a living from teaching alone wind up with grueling schedules at multiple colleges, punctuated by many hours of drive time. Some call these teachers “road warriors.”

Cash, for example, was at one point commuting nearly two hours each way to Plattsburgh, where she taught three classes on top of other adjunct jobs closer to home.

And Michael Allard, an associate professor who’s now chairman of the Division of Arts and Humanities at Columbia-Greene Community College, said he spent four years shuttling back and forth between adjunct positions at Columbia-Greene, just outside Hudson, and Hudson Valley Community College, in Troy, before landing his tenure-track position in 2005.

“At one point, I taught seven sections and drove almost 500 miles a week to get to work,” he recalled. “It was very stressful.”

On the lowest rung

The path for adjuncts is particularly tough at the region’s community colleges, where both full- and part-time faculty generally earn less than their counterparts at four-year institutions.

Liz Recko-Morrison, a past president of the faculty and professional staff union at Berkshire Community College in Pittsfield, said community colleges have long been expected to do more with less.

“Community colleges are the red-haired stepchildren of public higher education in Massachusetts,” Recko-Morrison said. “We serve 50 percent of the students but only receive approximately 25 percent of the higher-ed budget.”

At least in Massachusetts and Vermont, the state governments each fund unified community-college systems within their borders.

New York’s system, in contrast, is decentralized, with each community college sponsored by the counties from which it primarily draws students. A 1948 state law prescribes the formula for funding these colleges as one-third each from the state, county governments and tuition. But the state hasn’t been keeping its end of the bargain, and county funding averages only 18 percent.

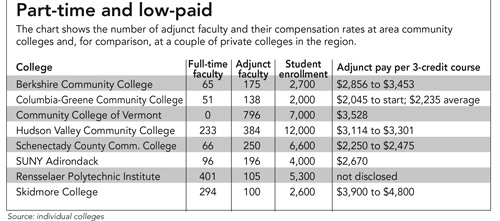

At Schenectady County Community College, which receives the lowest county contribution of any community college in New York, adjuncts are paid as little as $2,250 for a three-credit course. That’s the lowest compensation rate reported by any area college except Columbia-Greene, where starting pay for adjuncts is just $2,045 per three-credit course. (See accompanying chart above.)

By comparison, private colleges and universities in the region use fewer adjunct instructors relative to their size, and the pay appears to be somewhat better. Skidmore College, for example, pays adjuncts between $3,900 and $4,800 per three-credit course, depending on their seniority and the number of courses they teach.

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute wouldn’t disclose how much it pays adjuncts, but one former instructor reported being paid about $5,000 per course. Officials at Williams, Bennington and Southern Vermont colleges did not respond to requests for information for this story.

Changing business model?

The increasing shift to adjunct faculty in recent decades has occurred at a time when the cost of college tuitions locally and nationally has far outpaced inflation. At many schools, the number of administrators, and the value of their compensation packages, has grown rapidly. At the same time, colleges are investing heavily in new facilities and technology – moves that some say steer resources away from the actual classroom experience.

Derek Java, another part-time English instructor who teaches at three schools including SUNY Adirondack and Schenectady County Community College, is among those who see a case of misplaced priorities.

“If they can afford to build a $20 million building and hire administrators at absurd salaries, education really takes a back seat,” Java said.

Neal Herr, another adjunct at SUNY Adirondack, said that in higher education’s new business model, students have become customers in “the mall of knowledge,” investing in a ticket to a better job. Colleges now function as an industry, he said, turning out occupational value in exchange for tuition dollars.

Instead, Herr said, college should function as a democratic community of learners, where everyone is helping everyone else to learn rather than competing “for the buck, prestige or grade.” Higher education, he said, should promote critical thinking and broaden students’ horizons.

Java, 45, has two master’s degrees, but he said his income from part-time college teaching jobs never tops $25,000 a year, and he has been unable to pay down his significant student debt. He added that although teaching is very meaningful to him, he has only been able to stick with it because his wife earns a much better salary.

Earlier in his life, after completing his graduate studies in English literature, he operated an organic fair-trade coffee business.

“I was making money, but I wasn’t happy,” he said.

But as a college teacher, he said he takes pride in his role in developing human potential.

“Every semester, I see students improve in tremendous ways in their writing ability through guided practice,” Java said. “I believe that all people are capable of anything and everything, but they’ve been convinced otherwise.”

Banding together

Their low pay and tough working conditions have prompted adjunct instructors at some colleges around the country, including locally, to try organizing labor unions – or to consider affiliating with more aggressive unions in cases where they’re already part of a collective bargaining unit.

Adjunct Action, an arm of the Service Employees International Union, has lately been pursuing at least two organizing efforts locally. The SEIU already represents workers in at least 18 colleges in New York state.

Adjunct Action’s strategy involves organizing simultaneously or in rapid succession at multiple institutions in a given region. One reason for this strategy is that many adjuncts teach at several colleges. And from an organizing standpoint, significantly increasing the density of union membership in a metropolitan area or region ramps up the pressure to raise wages and working conditions across the entire region.

The SEIU scored the first victory in its Capital Region campaign in September, when adjuncts at the College of St. Rose in Albany voted for union representation by a nearly 3-1 margin. The next focus there will be negotiating a contract.

At St. Rose, adjuncts teach 30 percent of the college’s classes and are seeking better pay, health insurance, more job security, office space and a voice on campus. They currently earn about $2,400 per three-credit course and are limited to teaching only eight credits a semester.

Another organizing drive is under way at Schenectady County Community College, where adjuncts are signing cards in an effort to set a union election in motion.

Eileen Abrahams, the new president of the faculty and professionals union at SCCC and a vocal supporter of the adjuncts’ organizing drive, said the current pay rates for adjuncts are impossibly low.

The SEIU’s campaign may be targeting other area colleges as well, though union organizers try to keep their efforts under wraps until support at a particular college reaches a critical mass.

Although most adjuncts are not currently represented by a labor union, at some institutions they are folded into the same union and bargaining unit as full-time professors. That’s the case at SUNY Adirondack, where several years ago adjuncts gained a voice in the union; each adjunct faculty member now has one-fifth of a vote in union elections and decisions, compared with a full vote for each full-time member.

When Herr and a handful of other adjuncts at SUNY Adirondack got together early this fall to press for better conditions, they made a strategic decision to work within the existing faculty union for a year. If they aren’t satisfied with the progress, they say they’ll move to decertify and join a national union like Adjunct Action.

Some adjuncts contend that a union of full-timers cannot represent them because their interests are not the same and may even be in conflict, and because the concerns of full-time faculty tend to overshadow those of part-timers within the union.

And some part-timers say, only half joking, that they have more in common with workers at Wal-Mart or Dunkin’ Donuts than with their full-time counterparts.

Contrasts in Vermont, Mass.

Unlike community colleges in New York and Massachusetts, the Community College of Vermont has not established a two-tier system for faculty compensation. That’s because it has no full-timers among its faculty of nearly 800.

Hired by the semester to teach nearly 7,000 students at sites scattered around the state, CCV’s instructors are paid a standard rate of $3,528 per 3-credit course. Teaching assignments are capped at 11 credits per semester. CCV does not give tenure, reward seniority or offer a route for advancement, and being part-time, its faculty members are not eligible for health insurance.

At Massachusetts’ 15 community colleges, in contrast, all faculty, including adjuncts, and non-teaching professional staff, are represented by the same union, an affiliate of the Massachusetts Teachers Association called the Massachusetts Community College Council. Adjunct instructors belong to a different bargaining unit than full-time faculty and other professions, and they have their own contract.

One result is a pay scale that rewards seniority and the number of courses taught. The highest pay level requires eight years of continuous teaching.

“It was a big deal for me when I finally jumped to the top tier,” said Aidan Clement, who teaches anthropology and sociology at Berkshire Community College. His compensation peaked at $3,453 for a 3-credit course, with no further increases available.

But even $10,000 a semester represents a poverty wage. So even after 11 years as an adjunct at BCC, Clement has a second job in retail, mainly on evenings and weekends. He said he has turned down better-paying jobs with daytime hours that conflicted with teaching, which he enjoys immensely.

“Dealing with the students is the best part,” Clement said. “It’s rewarding sharing my subject with diverse students.”

A bad system for students?

Administrators often defend the use of adjunct faculty by saying the part-timers are needed to help colleges adjust to short-term fluctuations in enrollment.

But at each of the community colleges in the region, the number of adjuncts now far exceeds the number of regular faculty members.

Critics say colleges and universities have become addicted to the cheap labor that adjuncts provide, and they caution that poor working conditions for teachers can result in poor learning conditions for students.

Some of the risks seem obvious. Adjuncts shuttling between jobs at multiple colleges, for example, will necessarily have less time for preparing lessons and grading papers. They may opt for shortcuts that have less educational value, such as giving multiple-choice tests rather than assigning essays and papers. And teachers whose morale is flagging because of low pay or difficult working conditions are less likely to inspire their students.

Adjuncts also struggle to remain accessible to their students outside of class.

Some schools, for example, expect large numbers of adjuncts to share office space. At Schenectady County Community College, just one office is designated for shared use by about 80 adjuncts in the liberal arts division. Cash said that office contains just one working computer and printer, and three of its four desks are broken; one of the office chairs has both its arms held on by tape.

At BCC, by comparison, Clement shares an office with only two or three other part-time teachers.

“Mostly it’s me and a history adjunct that has been there even longer than me,” he said. “I have a desk I consider mine.”

But one recent incident left him scratching his head over his precarious status.

“When I came in one day between semesters to work on my syllabi, my desk was gone and all my papers and books were stacked on the floor,” Clement said. “We have three desks in the office. One was never used. Why didn’t they take the empty desk?”

His less-than-full status as a professor results in other absurdities.

“My students ask me all the time about my office hours,” Clement said. “As an adjunct, I’m not supposed to have set office hours. If I put them on my syllabus, I’m told to remove them. The reality is: How can you not have office hours?”

Having assigned a big research paper to his sociology class, he assured his students that he would make time to meet with them.

“How could I tell them, ‘If you have questions, you can only ask them during class?’” he asked.

Many of the adjuncts interviewed for this story said they feel invisible and unconnected to the life of the colleges where they teach. At some institutions, they aren’t even allowed a voice on issues central to their teaching, such as textbook selection and curriculum.

In Vermont and Massachusetts, however, the community college systems give part-time faculty financial compensation for participating in committees and other facets of college governance. That incentive makes it more feasible for adjuncts to contribute their expertise and perspectives.

Vermont and Massachusetts also are investing in their adjuncts by offering opportunities and funding for their professional development.

At BCC, Clement said he has enjoyed serving on work groups that delved into such topics as how the school can improve its teaching of critical thinking skills and its approaches to student assessment. Sometimes he gets a stipend for his service on committees and work groups; in other instances, the extra work is unpaid, he said.

Widely varying workplaces

The working conditions for adjuncts can vary widely from one institution to another.

One long-term adjunct, who asked that her name not be published because of fear for her jobs, said the situation at the two schools where she teaches, the University at Albany and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, offers a sharp contrast.

At UAlbany, she said, adjuncts and tenure-track faculty alike belong to United University Professionals, while Rensselaer is a non-union private university. At UAlbany, she receives regular increases in pay and occasional bonuses, while she has taught at Rensselaer for more than 10 years without a raise.

Like all four-year schools in the SUNY system, UAlbany provides benefits, such as health insurance and an employer match for retirement, for part-time instructors teaching at least two courses. RPI, in contrast, doesn’t normally offer benefits to part-timers.

Another adjunct who taught at Rensselaer for many years and spoke on the condition of anonymity because he fears he might not be rehired if he wants to return, said he became fed up with being part of a “completely disposable, interchangeable low-wage labor force” at an institution where administrator salaries “are up in the stratosphere.” (RPI’s president, Shirley Ann Jackson, is one of the highest-paid university leaders in the nation, with an annual salary of more than $2.3 million.)

He said it eventually occurred to him that he had control in one area: He could put less time into his job. By changing the way he teaches, he said he was able to get students more engaged while also reducing preparation and grading time.

The situation, he said, “forced me to become more creative as a teacher.” By his calculation, the resulting lighter workload translated into the cost-of-living raise the university had failed to provide.

Still hoping to move up

Before her teaching career, Cash had worked in music production and publishing. But when she reached her mid-30s, she decided she wanted to “give back” and returned to school, completing a master’s degree in education with a goal of teaching at the high-school level.

When she began applying for jobs, however, she found most public schools in the region were cutting back rather than hiring. She received one job offer, in a town near the Canadian border, and opted for personal reasons not to relocate there.

So she started her life as an adjunct with a job SUNY Adirondack.

Although she paid off her earlier student loans, Cash carries $40,000 in debt from her second master’s degree, which she obtained on the advice of a previous department head with the intent of making herself a more attractive candidate for a full-time college job.

“At the time I thought I’d be so hot,” she said. “What more would a two-year college want?”

Now, after five years as an adjunct, she still hopes to wind up working at just one school.

“I have great reviews,” Cash said. “There’s not one negative thing in any folder anywhere. Could you imagine how good I’d be if I were at one place?”