News

Farm-to-plate’s newest frontier

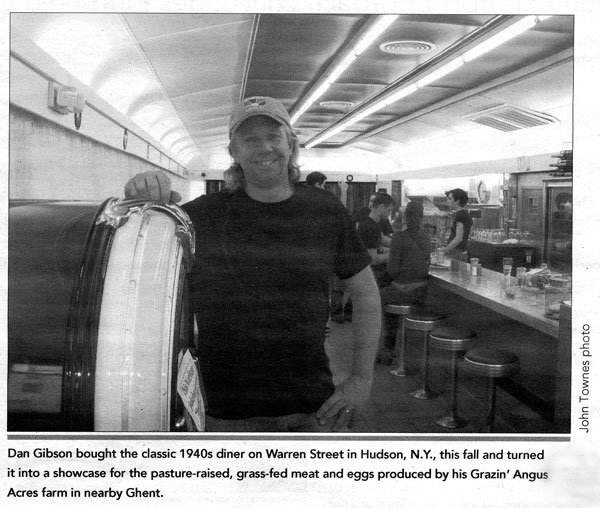

Farmer buys diner, serves up grass-fed beef

By JOHN TOWNES

Contributing writer

HUDSON, N.Y.

The ideal of farm-fresh ingredients has taken the restaurant business by storm over the past decade or so, but now the newly reopened stainless-steel diner on Hudson’s main street is taking the farm-to-table

concept to a new level.

At Grazin’, as the classic 1940s diner is now known, the farm and the tables are under the same ownership. The diner serves as a showcase for the pasture-raised, grass-fed meat and eggs produced by

its sibling, the Grazin’ Angus Acres farm in Ghent.

“We call it 'farm-to-table direct' because much of the food served at the diner comes directly from our own farm down the road,” explained Dan Gibson, who owns and operates the farm and diner in partnership

with his wife, Susan, and other family members as well as the farm’s managers.

Grazin' offers a holistic version of traditional diner fare, such as burgers, sandwiches and Sunday brunch. Although it has fewer menu options than a conventional diner, its owners put a much stronger

emphasis on high-quality, local ingredients.

Grazin' Angus Acres uses natural, biodynamic methods to raise its Black Angus cattle and its chickens and pigs. The animals graze on pastureland without cattle pens or traditional chicken coops. The

farm avoids the use of corn feed or artificial hormones or antibiotics.

The produce, dairy products and other ingredients served at the diner come from other local farms and producers that also emphasize sustainable farming practices and natural and organic products.

Grazin' has another distinction: It’s the first Animal Welfare Approved restaurant in the United States. The certification is granted by the national nonprofit Animal Welfare Institute, which certifies

farming operations that meet rigorous standards for sustainable and humane treatment of animals. The diner was able to obtain this recognition because its sister farm is AWA certified, and the diner

only deals with other vendors who meet those standards.

Post-9/11 transplants

Dan and Susan Gibson started Grazin' Angus Acres in 2002. The Gibsons, originally from Pennsylvania, previously lived in Westchester County, where Dan was a senior vice president of Starwood Hotels

and Resorts. They decided to make a shift from corporate to rural living after the Sept. 11 attacks.

The attacks “shook us up and caused my wife and I to re-evaluate our lives,” Gibson recalled. “We wondered what to do next. We eventually decided to look at buying farmland upstate. Although I didn't

have any farming experience, I’ve always been an outdoorsman, and it seemed like it would be suited to us.”

They bought a former dairy farm in Ghent. Gibson closed the dairy operation and bought a herd of Black Angus cattle at auction. Initially, Gibson continued with his corporate job, and the couple came

up on weekends.

“We were able to do that because Jim Stark, who previously had managed the dairy farm, stayed on as farm manager,” said Gibson, who noted that Stark and his wife, Ilene, are now partners at Grazin'

Angus Acres.

The Gibsons moved to Ghent on a full-time basis four years ago. Their son, Keith, joined the operation and is also a partner in the farm.

Grazin' Angus Acres products are sold directly at the farm and through farmers markets. Gibson said about 95 percent of their sales are through Greenmarket, a network of regional farmers markets in

the New York City area. Their meats also are featured at Local 111, a restaurant in Philmont.

Gibson said the diner venture came about as a result of both personal and business considerations.

“We really want to enable more local people to share in the bounty of our farm,” he said.

But he said the farm’s owners were frustrated because they weren’t able to get restaurants along on Warren Street in Hudson, a central commercial and dining district for the region, to buy their meats.

The opportunity to open a restaurant presented itself after their daughter Christine and her husband, Andrew "Chip" Chiappinelli, moved to the farm from New York City.

When he joined Grazin' Angus Acres, Chiappinelli initially worked on the sales side of the operation. Although he had never worked in a restaurant, his family had been in that business when he was

growing up, and he has had a lifelong interest in food. Gibson suggested that he operate a restaurant for the farm, and Chiappinelli agreed to become the diner’s manager and partner.

Downtown landmark

The diner where Grazin' opened this fall has a long history in Hudson. The stainless-steel building was shipped up the Hudson River and installed at its current site, across from Seventh Street Park,

in 1946. For decades it operated as the Columbia Diner and, in a more recent incarnation, as the Diamond Street Diner.

Although it had been a popular local gathering spot, the diner closed in 2009 because of unpaid taxes and other issues under its operator at the time.

“The diner had a difficult history, but I fell in love with the building,” Gibson said. “It’s a classic 1950s-style diner, and it is in a great location.”

Gibson bought the property at auction earlier this year and took possession of it in August. After an extensive cleanup, repairs and the addition of some new equipment, Grazin' opened for business

Oct. 1.

The 80-seat diner retains a traditional look, with some contemporary updates, including a flashing jukebox that continually plays golden oldies.

The menu at Grazin' includes a selection of grass-fed Angus burgers, at prices ranging from $8 to $15.50. These include specialized variations such as The Cowboy, which is topped with an egg and a

choice of artisan cheese or ham. For vegetarians, the menu includes The Bello, a marinated, grilled portobello mushroom cap. Sandwiches range from a grilled cheese for $7.95 to a ham club for $11.95.

Grazin' also serves soup, salads and french fries made with fresh potato slices. It offers house-made natural sodas, milk shakes and ice-cream desserts made with organic ingredients. There is also

a selection of local beer.

In some ways, the old diner’s rebirth reflects the transformation of Hudson over the past 20 years from a faded industrial city to a weekend retreat for New Yorkers. This winter, in anticipation of

the seasonal slowdown of visitor, Grazin’ is open Thursday through Monday, serving brunch on Sundays and lunch and dinner on the other days.

But Gibson emphasized that a primary goal of the business is to attract regular customers in the full-time local population who appreciated healthy food.

Although Grazin’s prices are somewhat higher than the norm for conventional diner fare, Gibson reacted strongly when asked about the oft-heard claim that there’s an element of elitism in the organic

and local-food movements because of the higher prices of those products.

“I strongly disagree with that,” he said. “Cheap food is just that – cheap. It’s not good for you. The prices in the mass-market industrialized food system also don't reflect the hidden cost in terms

of health, the environmental damage of factory farming and the loss of local agriculture.”

Gibson said quality food should be at the core of people’s budgets, no matter what their income level.

“It's a matter of priorities,” he said. “Is there anything more important than putting healthy fuel into your body? That's a much better use of money than fast food or other things that are bad for

you or things that are not as important in life. At the farm, I've had people in BMWs argue with me over the price of eggs. That doesn’t seem logical to me. And how much do people spend on things like

cigarettes while saying they can’t afford good food?”

Eating healthy food, he added, is affordable for those with modest incomes with a slight change in eating habits and budgets.

“You're better off eating quality meat fewer times a week than spending the same money to eat unhealthy meat every day,” Gibson said.

Rethinking farming practices

Grazin' Angus Acres farm started out as a registered Black Angus farm, selling seed stock to other farmers throughout the United States. Its emphasis on grass-fed, sustainable farming began around

2004, when a friend who has an autistic child and was pursuing a rigorous natural diet offered to buy one of the cows if it was only fed on grass.

Gibson began to do research on the merits of grass-fed farm animals and the drawbacks of corn feeding. That also led to a larger investigation of food production and distribution in which he read books

such as Michael Pollan’s “The Omnivore’s Dilemma,” Eric Schlosser’s “Fast Food Nation” and Nina Planck’s “Real Food,” among others.

The result was that Gibson became an ardent advocate of natural farming methods and a regional food economy.

In business terms, he also saw an opportunity to reorient Grazin' Angus Acres to become a local and regional supplier of pasture-raised meat and eggs for consumers.

“Cows are meant to eat grasses, not corn, and people are hard-wired to appreciate the difference,” he said. “Grass-raised meat is healthier and tastes better. However, in modern society we’ve been

conditioned to think that it’s more practical to eat foods that have been artificially raised and processed. But when people taste pasture-raised meat, they really enjoy it, because their bodies know

it’s good for them.”

Gibson noted that eating grass and other natural foods also causes chickens to produce better eggs, with orange yolks from the beta carotene in vegetation.

The farm’s operations are designed to be a symbiotic and sustainable system. Grazin' Angus Acres has, on average, about 300 cattle, 2,000 chickens and eight pigs on its 450 acres and other, rented

land.

“The cattle are a closed herd,” Gibson said. “It takes about three years to raise an animal on grass alone. Rather than buy calves to add to the herd, we raise them here.”

The farm’s chickens are also pasture raised. They are transported in an “eggmobile” to different sections of the property. In addition to grass, they forage for worms and other insects in the cow-patties,

which adds to the natural pest-control and fertilization process.

Throughout the year, as adult animals are ready for market, Gibson takes them in small numbers to Eagle Bridge Custom Meat and Smokehouse, a slaughterhouse at the southern edge of Washington County

that is Animal-Welfare approved. After slaughter, Eagle Bridge prepares the cuts of meat in packages for sale.

Gibson said the diner is handled as a wholesale customer of the farm.

“The diner and the farm are separate businesses that will each have to stand on their own,” he explained.

He acknowledged that adding the diner is a challenge.

“In some ways, we've chosen the two toughest businesses you can be in,” he said. “Farming and restaurants are both very capital-intensive, and they are not easy ways to make a living.”

But he expressed confidence that the restaurant can succeed. He noted that the farm has been able to hold its own and is supporting him and his family and partners.

“We have a different business model, because we are very focused,” Gibson said. “I think that if we provide people with something that's different, better and special, they’ll seek us out.”