Arts & Culture April 2019

Good, evil and a superhero

Artist’s mythical world takes shape in MoCA exhibit

A winding multi-colored pathway gives the feeling of being on a gameboard as it leads visitors through “Mind of the Mound: Critical Mass.” The show by artist Trenton Doyle Hancock opened last month at Mass MoCA. Photo courtesy of Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art

A winding multi-colored pathway gives the feeling of being on a gameboard as it leads visitors through “Mind of the Mound: Critical Mass.” The show by artist Trenton Doyle Hancock opened last month at Mass MoCA. Photo courtesy of Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art

By JOHN SEVEN

Contributing writer

NORTH ADAMS, Mass.

Every art show is the result of the artist’s imagination pouring out into reality, allowing ideas to seize tangible representation in the physical universe.

But Trenton Doyle Hancock’s new show at Mass MoCA, “Mind of the Mound: Critical Mass,” is also an effort to pull visitors inside the imagination of the Houston-based artist. The show offers an immersive experience in which the interior universe of his childhood co-exists in real space with the world of Hancock’s viewers.

Hancock is a painter, but the new show has given him the opportunity to take his concept of the “Moundverse” beyond the painting medium and to meld further autobiography with his creations.

The Moundverse compiles characters and situations that Hancock has had in his brain since he was a kid, and the show offers a winding multi-colored pathway that makes a visitor feel like they’re walking a gameboard into Hancock’s thoughts.

In Hancock’s vision, Mounds are peaceful plant-human hybrids that clean the environment. Their enemies, the Vegans, try to kill them, but the Mounds are protected by the hero Torpedoboy. From this basic scenario springs an entire universe of stories that Hancock has fashioned, starting at age 2.

“I can remember that far back to being one with the pencil and knowing that every time I went to the page, I was going to have an adventure,” Hancock said. “It was an addictive kind of a feeling, and it never stopped from there.”

The MoCA show, which opened March 9, features some actual, full-scale Mounds, as well as selections from Hancock’s massive toy and game collection, with Moundverse objects and toys placed among them, creating a kind of alternate-universe marketing hall of fame. There are also copious giant painted panels from the graphic novel he is currently working on telling the mythology behind the Moundverse.

Cultivating an imaginary realm

Cultivating an imaginary realm

As Hancock was growing up, he was influenced by toys and especially comic books like Spider-Man and Iron Man. He was raised in Texas in a family of evangelical Baptist ministers and missionaries, and his parents’ strong religious beliefs led to conflict. His mother especially would target his and his brother’s pleasures as the devil’s work and trash them. Action figures were frequent victims of this spiritual cleansing of his childhood fun.

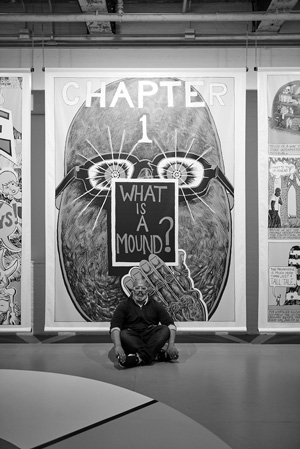

The artist Trenton Doyle Hancock sits in front of one of the panels at the show. Photo courtesy of Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art

“Perhaps it was that they projected this air of my male machismo, but also coupled with images that she perceived as definitely, indisputably evil, like skulls or things like that,” Hancock said. “That’s where the red flags went up. That was a good portion of the toys we had at the time. So we feel like our collection got wiped out in a big way.”

Oddly, certain movies and video games escaped persecution, and those shaped his worldview far more than his parents’ Christianity.

“It’s funny what stuff slipped through the radar and what didn’t,” Hancock recalled. “I go back and I’m confused as to something that my mom chose to leave and other things that she was like, ‘That’s too much, you’ve gone too far, we have to get rid of that.’ I was able to keep all my video games that had what she would consider cultish information in them. Perhaps she just wasn’t looking too closely.”

The Garbage Pail Kids were definitely evil, though. So was Dungeons & Dragons. They ended up tossed in the fire. Eventually Hancock and his brother figured out what would pass and what wouldn’t.

“We played it safe from there on out,” he said. “We were able to subversively figure out ways to get stuff into the house. Because we didn’t give a crap about our eternal souls -- I’m not 100 percent sure if we believed it all. We just thought, ‘Oh, our mom is crazy.’”

Material belongings could be destroyed, but his imagination was untouchable. Hancock began to create characters that spoke to his life. His first, Torpedoboy, appeared in fifth grade, the result of Hancock starting to wear glasses.

“The relationship I have to him is the Clark Kent/Superman sort of relationship,” he said. “That character has evolved with me since then.”

Hancock wrote short stories about Torpedoboy on lined paper, accompanied by illustrations, and the Moundverse was born. By high school, he had embraced comics and was creating strips and gag panels for the school newspaper.

“From around fifth grade to the end of high school, I was quite determined to become a comic book artist,” Hancock said. “That’s how I felt I could contribute to the world, to find my voice outside of school. I thought, ‘When I graduate, I’m going to take my portfolio and go work for Marvel.’”

From comics to high art

His artistic path took a turn in college at the Tyler School of Art at Temple University, where he studied graphic design and began to envision a life in fine arts. Joseph Campbell’s writing about the hero’s journey had crept into his Moundverse ideas, and at the same time he found inspiration from Todd McFarlane’s creator-owned Image Comics and discovered cartoonists like Art Spiegelman and R. Crumb.

“That’s the point where things really started to become clear to me that I didn’t have to choose, I didn’t have to be a comic book artist or a painter,” Hancock said. “I could really put together something that was a composite of both of these ways of thinking.

“It was a little bit more of a layered way of thinking about narrative -- or at least a poetic way of thinking about it. I wanted to go against that grain and create something that I thought could do it all. You could not only have paintings that operate as paintings but also as signifiers for something else.”

Eventually the Moundverse moved beyond paintings. In 2005, a collaboration with Ballet Austin in Texas used the Moundverse as inspiration and saw Hancock creating all the sets and costumes.

“It answered that question that I always thought: What do these characters look like when they’re moving?” Hancock said. “What do they do? And so this helped me understand better who my characters are and what their potential is, and also think more about sculpturally about them.”

Hancock followed the ballet collaboration with public art projects in parks, hospitals and stadiums that helped him think adventurously about scale and access to his Moundverse ideas.

“I’m like, whoa, now everyone’s going to be able to have access to this stuff, not just people who go to museums,” he said. “Like if you go to the park, if you’re at the hospital, you can see this stuff. And I started feeling even better about what could happen for the future.”

Hancock said his experience of going booth to booth on a visit to the San Diego Comic-Con in 2015 fueled the gallery presentation of the Moundverse at Mass MoCA. He also was inspired by trips he and his wife have taken to theme parks, where he studies how the layout and the rides construct narratives within each park.

“That also plays into building a show like this where it’s like you’re walking through and you’re guided by this invisible force and you happen upon these experiences,” Hancock said. “It mimics how we move along our archetypal journey from these hot spots in our life.”

Returning to his original inspiration, comics, Hancock began working on a graphic novel of the Moundverse in collaboration with his friend, comic book artist Tom Neely, as colorist. Samples of this work now hang at Mass MoCA, and Hancock plans to compile them into book form telling the story of the Moundverse, which is also the story of Trenton Doyle Hancock and the lessons he has learned.

“I think there’s a sense in the Moundverse of trust yourself, trust your own rhythms and trust your own intuitions at all costs,” Hancock said. “Because you have to do that hard work of finding the self and trusting and believing yourself before you can help others. It’s sort of like on an airplane. You’ve got to put your oxygen mask on before you can help the person next to you.”