Editorial August 2017

E D I T O R I A L

In water crisis, states reveal differing political cultures

It hardly comes as a surprise that when faced with a crisis, Vermont’s state government would perform a whole lot better than New York’s.

We already knew, from so many news stories over the years, that Vermont still functions as a representative democracy – and that New York has, well, Albany.

But it’s still a bit stunning to see how much of a difference that makes in real-life situations affecting ordinary people.

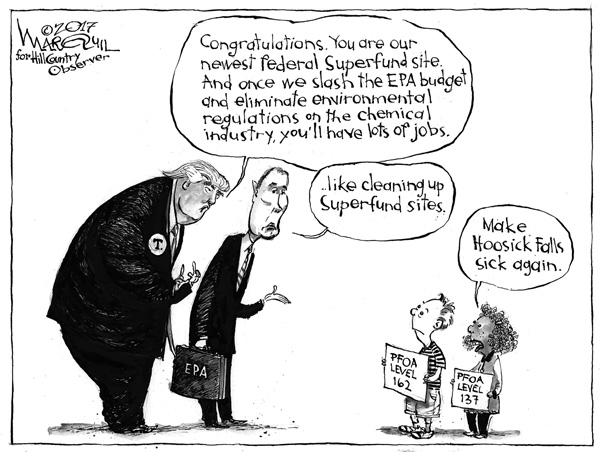

Our cover story this month explores and compares how the two states have responded to the discovery of the industrial toxin perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA, in the water supplies of two local communities. Hoosick Falls and North Bennington are only about eight miles apart, but the state line between them seems to have made a world of difference.

In Hoosick Falls, tests beginning in 2014 showed PFOA in the village water at concentrations well above a federal advisory limit that was then 400 parts per trillion. But New York health officials waited more than a year before telling the public not to drink the water – and then only after federal environmental officials forced the issue.

In North Bennington, tests in February 2016 turned up PFOA in the well water near a defunct factory that had used the chemical. The next day, Vermont environmental officials held a public forum in North Bennington, warning anyone within 1.5 miles of the plant not to drink their water until more thorough tests were done. State officials then went door to door to test individual homeowners’ wells and soon documented contamination affecting about 200 homes. About a week after the first tests, a state contractor was delivering bottled water to all homes in the affected area.

In Hoosick Falls, no one went door to door. The 4,000 customers of the village water system were told they could pick up bottled water for free at the local supermarket. A group of local volunteers organized to deliver jugs of clean water to the elderly, sick and disabled; this continued for several months before the village government decided to take responsibility for this service.

Last month, Vermont’s governor announced that Saint-Gobain, whose plants in North Bennington and Hoosick Falls used PFOA before the chemical was phased out a few years ago, would fund a $20 million project to extend public water lines to about 200 homes in North Bennington that were affected by PFOA.

In Hoosick Falls, state health officials say a filter system installed last year has made the village water safe to drink again. But the wells that supply the village water remain heavily contaminated with PFOA and two other industrial chemicals. There’s talk of connecting the village to a clean water source, but no real plan has been developed.

To be fair, the differences in the way the PFOA crisis unfolded in the two communities are partly a function of timing. Hoosick Falls was the first to make headlines, and by the time PFOA was discovered in North Bennington, lots of minds had already been focused on the chemical’s risks.

There also might be dividing lines of class and economics. Hoosick Falls has historically been a mill town, and Saint-Gobain remains a large employer. North Bennington is a college town, with a plant that was shuttered 15 years ago.

But a lot of the difference is the result of the states’ distinct political cultures, which are partly driven by their vast differences in population.

Vermont’s government is a lot closer to its people – and it shows.