News & Issues December 2016-January 2017

Meditation for the masses

Yoga center’s program offers ‘mindfulness’ as a tool for social change

By TRACY FRISCH

By TRACY FRISCH

Contributing writer

BENNINGTON, Vt.

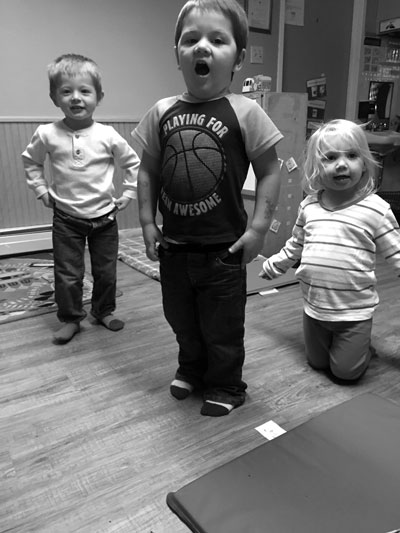

Children in the early education program at Sunrise Family Resource Center in Bennington try “breathing like lions” as part of their daily mindfulness exercises. Nicole Bushika photo

At the Sunrise Family Resource Center in Bennington, toddlers in the early education program spend a little time each day on “mindfulness” exercises -- crouching like frogs, breathing like lions and spreading their wings like butterflies.

In Pittsfield, social workers at Pittsfield Community Connection use techniques borrowed from yoga, like stretching and conscious breathing, in their work with at-risk youths learning to control angry or violent impulses.

And at high schools in Pittsfield and Great Barrington, physical education courses include an elective yoga class whose students, some teachers report, emerge with a new sense of focus on their academic work.

These are just a few examples of the wide-ranging impact from a two-year-old program in which the Kripalu Center for Yoga & Health set out to share the benefits of yoga and meditation with people who otherwise might never have encountered them.

Like other prominent institutions and retreats dedicated to meditation and holistic health, Kripalu normally caters to the affluent. Scholarships allow some people of lesser means to attend Kripalu’s life-changing programs, but financial aid alone can’t begin to break the barriers that prevent those with fewer resources from gaining access to what the center’s literature calls “the transformative wisdom and practice of yoga.”

So Kripalu, which describes itself as North America’s largest residential facility devoted to holistic health and education, has been trying new strategies for reaching “underserved populations.”

The center, based in a former Jesuit seminary on 350 acres in Stockbridge, Mass., identifies its mission as “empowering people and communities to realize their full potential.” The question is how to provide that empowerment to people without the luxury of disposable income.

“Many of the people who need it the most can’t come to a yoga studio or Kripalu,” said Edi Pasalis, the director of Kripalu’s Institute for Extraordinary Living.

Two years ago, the institute launched a new five-day immersion program for “frontline professionals.” That’s Kripalu’s shorthand for social workers, educators and others in the human services field – people who work directly with those living in poverty or struggling with the effects of violence, abuse or addiction.

“We work with a whole spectrum of organizations in education, health care and law enforcement,” Pasalis explained. “Some have clients who are prone to violence or getting upset and out of control.”

So far, the institute has offered the immersion program six times, to a total of 145 participants.

Finding calm and focus

Finding calm and focus

photo by George Bouret: At the Sunrise Family Resource Center in Bennington, Denise Main, Amelia Silver and Lindsay Errichetto all use techniques from yoga and meditation in their work.

Pasalis, who left a corporate career to study and teach yoga, speaks passionately about making “the skills that yoga helps people cultivate” more widely available. Those skills aren’t merely about physical objectives; rather, in the immersion program, yoga skills fall under the headings of calm, clarity and connection.

Early in the program, participants learn controlled or conscious breathing.

“It’s very profound and also the quickest and easiest way to engage the relaxation response,” Pasalis said.

Another facet of the program introduces the practice of “mindfulness” in meditation, eating and movement.

“We also talk a little about nutrition and the impact of what you eat on how you feel, so you can make wise choices,” Pasalis explained. “We then talk about how they can apply these new skills in their work. They might be doing community outreach with opioid-addicted youth or working within the context of the school day.”

Schools, nonprofit organizations and government agencies send staff members to the Kripalu immersion program at no cost. Kripalu aims to train enough people in each organization to ensure that what they learn will “take root” – and that colleagues can support one another in applying their new skills.

By taking teachers, social-service providers and others out of their normal environment, the five-day immersion program helps to create more meaningful and lasting change, organizers say.

“Kripalu is a safe and sacred space where people are able to try something new,” explained Jill Bowman, a Kripalu vice president. “They’re practicing every day when they’re here. They find out how they feel eating healthy food ... when they’re not caffeinated and eating lots of sugar.”

Pasalis said one young man who works in youth services was so ground down when he came to Kripalu that he commented the immersion program “helped him remember the happiness of being alive.”

Working with these frontline professionals is particularly rewarding, Pasalis said, the more so because the lessons they learn at Kripalu carry benefits back to their own workplaces.

“One of the great motivators is to help people who are doing very difficult work to sustain themselves,” she said. “We find that these tools help the overall culture of the organization become more positive and impactful.”

Measuring the impact

The Kripalu Institute for Extraordinary Living is working with Harvard Medical School researchers to determine the benefits of its program for frontline professionals. The preliminary results are very positive, Pasalis said.

“Mindfulness and stress resilience both go up, and people feel better in their work,” she explained.

In the future, Kripalu expects to look more at the indirect effects the program is having on the people the frontline professionals are working with. This inquiry might start with relevant metrics that already have been collected, like the number of violent incidents or recidivism among clients of social service agencies whose staffers have gone through the immersion program.

But for now, Pasalis said, people are already offering anecdotal reports of qualitative changes and successes with the people they serve.

“The folks from Pittsfield Community Connection work with young people living in a culture of violence,” Pasalis said. “They have used these tools to help build bridges.”

Jon Schnauber, executive director of the Pittsfield Community Coalition, offered one story to illustrate the point.

“Last summer, two young men were literally shooting at each other and at each other’s homes,” he said. “Both are now in our Safe and Successful Youth Initiative program. When one of them found out that the other one didn’t have any money, he bought him groceries.”

Pasalis said the young men involved were able to use the tools of meditation “to calm themselves down.”

“They were able to see each other as human beings who were suffering and shift their relationship,” she explained.

Another illustration of how Kripalu is making a dramatic difference comes from Woodside Juvenile Rehabilitation Center, a state institution in Colchester, Vt., near Burlington. Pasalis said Woodside has a history of using physical restraints on its young inmates.

Now, she said, the center’s staff is teaching some of its inmates to use focused breathing, borrowed from yoga, to de-escalate situations that might otherwise lead to the use of restraints. Woodside did not make a representative available for an interview for this story.

Benefits for staff and clients

Another organization that has put staff members through the Kripalu program is Sunrise Family Resource Center in Bennington, one of Vermont’s 15 parent-child centers. Under a system created by the Legislature two decades ago, each county has a center charged with providing comprehensive services for families in poverty.

Sunrise’s 28 staff members deliver more than a dozen programs to some of the area’s most vulnerable citizens. These programs range from on-site education for teenage parents to care and education for infants and toddlers up to age 3. Case managers offer wrap-around services to minors receiving welfare, and advocates work with families at risk of losing custody of children because of neglect or abuse. Another program helps young people transitioning out of foster care.

Sunrise also provides training and oversight of home-based childcare providers in Bennington County and hosts parenting classes, dads groups, playgroups and a job club. And that’s not an exhaustive list of the center’s offerings.

“This is the kind of work people do who are deeply committed to strengthening families,” said Amelia Silver, the development director at Sunrise.

So far, seven of Sunrise’s employees have participated in Kripalu’s five-day immersion program. Silver has written a grant proposal for funding to send the rest.

“The more staff are able to stay calm and breathe, the better our work is going to be,” she said.

Silver said that when she went to the Kripalu program herself, she had expected it to be something of a vacation. But instead she found herself gaining “layers and layers of insight at all the workshops.”

One rewarding aspect of the Kripalu program, she said, involves the sharing that takes place among people who are brought together for five days from a wide range of social service organizations. Each participating organization works in a different way, and talking about their work and its stresses engenders mutual respect.

One of Silver’s central takeaways was to reflect on how she and her peers deal with stress. She said she considered questions like, “How do we as leadership staff respond to stress? What are my patterns when I’ve got my back up against the wall, or I’m disappointed, like when someone I put a lot of energy into has relapsed?”

She said she was drawn to “the idea of regulating yourself so you can help others regulate themselves.”

Self-regulation, she said, is something done “at the most physical level.” It involves things like slowing down, breathing, doing yoga exercises to center yourself and feeling where in your body you’re holding stress.

“That act of going inward can change an hour or a whole day,” Silver said.

Staying focused amid turmoil

Lindsay Errichetto, the Sunrise center’s executive director, said her experience at Kripalu reinforced the notion that having your cup full – as opposed to being depleted – is an obligation.

“We all wrestle with burnout and turmoil,” Errichetto said.

Being fully present for clients requires a conscious effort and daily practice.

Silver said she used to feel “a little guilty” about taking time every morning to make a full breakfast with her boyfriend.

“Kripalu gave me permission to do that,” she said.

Rather than viewing breakfast as an indulgence, she explained, she has reframed it as a mindful routine, a form of self-care.

Silver described herself as being apt to move “way too fast” and to be “pretty cerebral.” But the week she returned from the Kripalu retreat, she was able to sit still in her swivel chair with her feet planted firmly on the floor as she supervised five people.

“You feel so much more effective and connected when you breathe,” she said.

Denise Main, the child development director at Sunrise, said that at the organization’s Thursday morning staff meeting, she and her colleagues sometimes start by breathing together.

“When someone dashes in for supervision, we might sit and do some breathing before we start talking,” she said.

That effort to remain mindful and centered carries over into work with clients, she said.

“For people with trauma, ritual helps provide safety,” she said, explaining that such a routine can be established by, for example, doing a conscious breath exercise together with a client at the start of a home visit.

“People’s lives are chaotic,” Main said. “Our job is to pull that back.”

Breaking cycles of trauma

Sunrise puts much of its effort into breaking the cycle by which psychic trauma is passed on from one generation to the next.

“All our parents love their children very much,” Main said. “They say, ‘I want to do a better job than my parents.’”

But people who didn’t receive adequate parenting as children often have difficulty being good parents themselves.

Main pointed out that Sunrise’s childcare staff is closely attuned to toddlers’ need to play. But when some of these young children go home, they aren’t being played with.

“The expectation is that children fit into the life of the parents,” Main said. “Children get bossed around a lot. They aren’t attended to.”

Silver said virtually all of Sunrise’s clients have some effects of psychic trauma. Risk factors for trauma, she said, include having an incarcerated parent or divorced parents or experiencing domestic violence, parental substance abuse, homelessness and housing instability, physical, sexual or emotional abuse, or chronic neglect in which a child’s emotional, developmental or physical needs aren’t met. Clients may have experienced several, even many of these risk factors.

The entire staff at Sunrise has been trained to understand psychic trauma and its manifestations – and in how to respond in ways that avoid giving people more traumatic experiences. But healing from trauma requires getting out of one’s head.

“We’re such a talk, talk, talk society,” Main said. “But we all know that trauma sits in the body, and the way to work it out is through the body.”

That’s one place where Kripalu’s yoga tools come in.

Errichetto said trauma’s physicality was made clear to her in a recent experience. One week she decided to “have a red rose Tuesday,” she said.

“One of the students lit up when I went to hand her a rose,” Errichetto said. “She was reaching out her hand, but her body froze. It was such a visceral gut core reaction. She was looking at the stem to make sure I wasn’t going to hurt her.”

Such deep-seated fear is frequently the driving force among people exposed to a lot of trauma. Several years ago, Sunrise had a teacher who also had a yoga studio in town. She would do yoga with the teenage students, though many of them didn’t participate.

“Closing your eyes where you’re lying on the floor was too scary for them,” Silver said.

One segment of the Kripalu immersion program is called “Riding the Wave.” When a wave comes barreling in, one’s immediate impulse is often informed by fear, but such a reaction may unleash a cascade of negative consequences.

Kripalu teaches people to pause so they can figure out how to handle the situation with awareness. And as any surfer knows, every wave comes to an end. They are always finite.

So if one’s child is having a meltdown at the supermarket, taking a moment to consider how to respond doesn’t further harm the child, Main said. The task is to stay calm when your child cannot, she explained.

When the Sunrise staff presented a series of parenting classes this year at the invitation a Bennington elementary school, they introduced the metaphor of riding the wave. Main said she was pleased by the power that the idea held for parents. In subsequent sessions they talked about making it through and realizing that there would be an end.

Controlling anger, stopping violence

At Pittsfield Community Connection, Schnauber introduced himself as a trauma survivor and combat survivor – he served in the military in the first Persian Gulf war and in Afghanistan -- before mentioning his role as a social worker.

Schnauber and his staff of nearly a dozen work with at-risk and proven-risk youth – people ages 10 to 24 who are considered unlikely to succeed in life or have already become entangled in the criminal justice system.

“Going to Kripalu brought it all together for me,” said Schnauber, who’s been a student of Buddhism and eastern philosophy for about 20 years. “It worked really well.”

Five people on his staff have been trained at Kripalu, and he plans to send the rest in 2017. He expects Pittsfield Community Connection to gain the distinction of being the first organization involved with the Institute for Extraordinary Living to have all of its employees trained at Kripalu.

“A lot of our clients have issues around emotional turmoil, but no one ever talks to them about emotions,” Schnauber said.

He’s developing classes that use Kripalu practices, like breathing and stretching, along with psychosocial explanations, like the fight-or-flight mechanism. He has already incorporated Kripalu’s techniques into the anger management program he teaches.

“These are tools that can be used any place, any time,” Schnauber said. “We can transfer the same skills very easily to the troubled kids we work with. They can be done in the office or on the street, and they’re adaptable to real-life situations.”

Pittsfield Community Connection’s staff includes some former gang members.

“They use these techniques on the kids and get results,” Schnauber said.

One of the organization’s outreach workers owns a gym, where he takes clients for recreation. This worker initially was “extremely skeptical” about the value of techniques borrowed from yoga, Schnauber said.

“Now he’s completely bought into it,” he added. “He’s incorporating some of these techniques in his gym.”

Rachel Hanson, a social worker who’s the program manager at Pittsfield Community Connection, recently moved to Massachusetts from London with her husband. She works full time while pursuing her master’s degree.

“Kripalu changed my life,” Hanson said. “It allows me to keep myself in balance.”

Now she meditates regularly, and she plans to take up yoga when she finishes her degree.

At Kripalu, Hanson said she learned to let go of what she can’t control – to “ride the wave.” The experience also gave her tools to get in touch her feelings and to work through problems rather than shutting down emotionally. She said there are obvious parallels with the young people she works with.

“We create a safe space here for them to open up and be honest about what they’re going through,” she explained.

The young people her group serves come in with traumatic stories, and being around all that suffering isn’t easy, Hanson said. But now she relies on conscious breathing to help her get through the day.

Pittsfield Community Connection multiplies the impact of the Kripalu skills through clients who act as peer mentors to other young people served by the organization. Peer mentors have been in the program longer and have developed their powers of self-control and self-regulation.

Some of what they teach the other young people, such as mindfulness, comes from Kripalu. There’s a discipline to noticing when you’re about to blow up and deciding to step back, instead of lashing out and escalating situations into full-blown conflict.

“It’s living proof that it works,” Hanson said.

High-school yoga classes

Two high schools in Berkshire County offer Kripalu yoga classes for their students. Kripalu started the program at Monument Mountain Regional High School in Great Barrington, and it later spread to Pittsfield.

Lisa Hoag, chairwoman of the physical education department at Pittsfield High School, said she received “a random call” about seven years ago. The co-creator of the Kripalu Yoga in the Schools program was offering to bring the program to her school.

After three years of Kripalu faculty teaching yoga classes at Pittsfield High, Hoag agreed get certified in yoga instruction. First she needed to complete the basic 200-hour course for yoga teachers, quite a feat for someone who was new to yoga. Now she’s been teaching yoga at her school for several years.

In that time, Hoag said she’s gained a much deeper understanding of yoga and has cast-off old assumptions.

“It’s not about the headstand or the flexibility,” she said. “There’s so much more to yoga than that.”

At Pittsfield High, students in all grades have physical education twice a week. Every four weeks, they choose an activity from three different options. When yoga is offered, it runs for two rotations, so students get 16 yoga classes.

“The first few classes are on self-regulation and the benefits of breathing,” Hoag said. “We talk about the things that stress you and what you do about them now.”

Hoag recalled on student, a homeless girl who had lived with her mother in Las Vegas and Connecticut and was back in Pittsfield.

“One day she asked to use my bathroom,” Hoag said. “Later I found a note on my computer. She wrote that ‘a lot of what you’re saying reminds me of my therapy sessions. It brings me back into focus.’”

Hoag also remembers a ninth-grade boy who told Hoag he was using the breathing he learned in yoga.

“I asked him if he noticed any differences in his relationships,” she said. “He said he and his younger brother don’t argue and banter anymore.”

A couple years ago, a science teacher had a hunch that students were coming to her class right after yoga. She observed that they had “a whole different demeanor” and “were settling in faster,” Hoag recalled.

Pittsfield High has embraced wellness and mindfulness as part of its school improvement plan. Principal Matthew Bishop is working with Kripalu on how to implement it, Hoag said.

“Hopefully,” she said, “it will just become the normal culture of the school, like we have purple Fridays for team spirit, even if it starts with just one day of mindfulness.”