News

Wiped off the map?

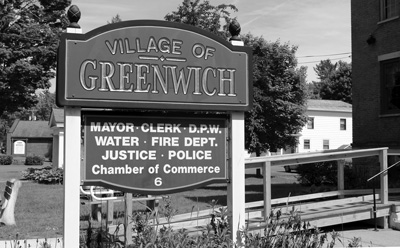

Village governments face elimination in N.Y. push for consolidation

By THOMAS DIMOPOULOS

Contributing writer

GREENWICH, N.Y.

The two buildings sit about 20 yards apart across a parking lot: The red brick structure houses the municipal offices of the village of Greenwich, while the white-columned building next door is home to offices of the town of Greenwich.

The two buildings sit about 20 yards apart across a parking lot: The red brick structure houses the municipal offices of the village of Greenwich, while the white-columned building next door is home to offices of the town of Greenwich.

But the dividing line between the two properties could soon be erased. On June 24, local voters will decide whether to do away with the village government in Greenwich. Services the village now provides would either be eliminated or taken over by the town and the neighboring town of Easton.

A similar vote is scheduled for August in the village of Salem, 12 miles to the northeast. And more village governments across eastern New York could soon be targeted for elimination, thanks to a new state law that makes it much easier for citizens to petition for government consolidation.

To supporters of the change, the side-by-side town and village offices in Greenwich offer the perfect symbol of overlapping, duplicative layers of local government that are blamed for driving up the tax burden in New York. The town has a supervisor, clerk and tax collector, four council members, a highway superintendent and a town justice, among other officials, while next door the village supports its own mayor, clerk, board of trustees and a separate public works department and village justice.

Consolidate the two governments, advocates say, and it stands to reason that services can be provided more efficiently, with fewer employees and at less cost to taxpayers – particularly for village residents, who currently pay taxes to support both the village and town.

But others say that in communities that already have considered dissolving their village governments, the tax savings have been underwhelming at best. And opponents fear eliminating the local government would cost the village its identity as well as services – such as local police protection – that the surrounding towns are unlikely to step in to provide.

And despite the appeal of potentially lower tax bills, voters in more than two-thirds of the New York villages that have debated dissolution in recent years have rejected the idea.

Touting tax savings

The village of Greenwich has existed as an incorporated entity since 1809, although it went by another name prior to the 1860s. The petition drive that might lead to its elimination was started earlier this year by Peter Gregg, the new publisher and editor of a local newspaper.

“The state put out a financial incentive for villages to dissolve,” Gregg said. “We decided to start the petition and move the process forward.”

Gregg has lived in the village for 18 years and runs Atticus Communications, a public relations firm and producer of several agricultural publications. In September, he took over The Journal-Press, a 170-year-old weekly paper in downtown Greenwich whose previous owner was on the brink of shutting it down.

In recent months, Gregg has pushed the idea of dissolving the village government in a series of front-page commentaries, starting in February with a piece headlined, “It’s gonna take a village to do away with one.”

“Us villagers have to pay the village tax and the town tax even though we really do not get any town services for the tax we pay,” he wrote, arguing that there is an unnecessary overlap of services and municipal employees between the town and the village. “There’s an opportunity for us to lower our taxes.”

State pushes consolidation

The concept of dissolving villages and consolidating services with neighboring municipalities is not a new one. Since 1900, 48 villages in New York have been eliminated, with eight of those disappearing in the past five years, according to the state Department of State. Three others (Keeseville, Bridgewater and Lyons) are scheduled for dissolution by the end of 2015.

Over the past 25 years, dissolved villages have outnumbered newly incorporated ones by a 2-1 margin.

But the process for eliminating village governments became much easier in 2010 with the enactment of legislation championed by Gov. Andrew Cuomo. Two years earlier, Cuomo, then the state attorney general, began calling for streamlining local government in New York with the goal of reducing the state’s tax burden, citing the existence of what he said were more than 10,000 local government entities across the state.

The new law, officially called the New New York Government Reorganization and Citizen Empowerment Act, allows dissolution of village governments to be put to a vote if 10 percent of the registered voters in a village sign a petition calling for a referendum.

“The threshold before was higher, and there is also a much quicker time frame now,” said Tim Weidemann of Rondout Consulting, who has been hired by the village of Greenwich to lead a team studying the potential effects of dissolving the village government.

“I haven’t analyzed it, but my take is there has been an uptick in villages studying or holding a referendum” since the new law took effect, Weidemann said.

The easier process for dissolution advocates doesn’t guarantee success at the polls, however. According to the Empire Center for Public Policy, 33 villages in New York held referenda on dissolution proposals between 2008 and 2013; of those, voters in 23 rejected the idea.

A few miles west of Greenwich and just across the Hudson River, the Saratoga County villages of Victory and Schuylerville each voted against dissolution, in 2013 and 2011 respectively. A move to dissolve the Saratoga County village of Corinth also was voted down in 2012.

Town and village employees generally fear that consolidation will lead to job losses, and they and their families may constitute a sizeable voting bloc, particularly if turnout at the polls is low.

And Weidemann said having towns absorb villages doesn’t necessarily result in significant tax savings, although his estimate of the financial consequences of dissolving Greenwich wasn’t completed as of late May.

“We’re just assessing that now,” he said. “Generally, village residents save a decent but not a huge amount. And generally those outside see an increase in taxes. But that doesn’t mean that would be the case here.”

Vote first, answers later?

The big question in any village dissolution, Weidemann said, is “what happens to the services that were provided by the village.”

For example, will water and sewer services and police and fire protection be taken over by the surrounding town or towns – or by special districts created to collect taxes or user fees previously handled by a village?

Weidemann said all options are on the table in Greenwich. The short time frame between petition and referendum leaves little time to come up with realistic financial estimates.

In Schuylerville, which considered dissolution under the legal system in place before the 2010 law, consultants completed an 18-month study before the village’s voters weighed in. Under the new law, the vote essentially comes first, and the bulk of the study comes later.

“In Schuylerville, we spent a lot of time working with various options,” Weidemann said. “In this case, with limited time before the referendum, we can’t do all that. We know sewer and water will not go away, but it remains to be seen who will provide that service.”

Further complicating the assessment in Greenwich is that, while most village residents are in the town of Greenwich, a portion are within the neighboring town of Easton.

Only registered village voters may take part in the referendum. There are a total of about 1,000 eligible voters, with about 100 of those in Easton.

If a majority of the voters who turn out on June 24 support dissolution, village officials will be required to meet within 30 days to discuss how to proceed. They then have 180 days from that meeting to approve a dissolution plan.

The village will host public hearings and possibly revise or amend the plan adopting a final version. Dissolution would take effect on the date specified in the plan, which could be as early as 45 days after the final plan is approved.

“My sense is that would happen no sooner than December 2015 and possibly into 2016,” Weidemann said. “I can’t speak for the board, but that that would be my recommendation.”

Any board-approved plan can also be undone during the 45-day period before the plan takes effect. To stop dissolution at that point, 25 percent of registered village voters would have to sign a petition to force a second referendum asking whether the dissolution plan should take effect. If that second referendum is initiated and dissolution is voted down, the dissolution process could not be initiated again until at least June 2018.

Police services, land-use rules

Village officials say they hope to provide voters with as much information as possible prior to the June 24 referendum.

Mayor David Doonan said he wished the study of dissolving the village government and sharing services with neighboring communities had come about in a different way.

“To address all of these issues and to attempt to do this in six months is clo

se to impossible,” Doonan said. “It came completely out of the blue, and I’m saddened the people circulating the petition did so without getting the village involved. If they had approached us, we could have had a process to develop a plan, to adopt a plan, and to give voters a lot of the knowledge they need to know about what they’re voting on.”

In contrast to a voter-initiated dissolution, one initiated by a governing body presents a proposed plan before voters head to the polls to decide whether to consolidate or dissolve.

“It’s a tight deadline, so I chose to be proactive because we have a complicated situation with two different towns involved,” Doonan said.

In addition, the village has an agreement under which it shares police coverage with the village of Cambridge, 8 miles to the southeast.

Cambridge-Greenwich Police Chief George Bell has four full-time officers and a sergeant plus 14 part-time officers to patrol the two villages. If dissolution is approved, Bell said he anticipates at least two full-time officers will be out of jobs, and he said it remains to be seen how big a police department the village of Cambridge would be capable of supporting alone.

Also to be decided is what to do with the equipment the department acquired under the shared services agreement. The village police department in Greenwich could be converted into a townwide department or eliminated altogether, in which case the Washington County Sheriff’s Department and State Police would be responsible for covering the former village.

Another question to be resolved is what will become of the village’s planning and zoning rules. Under state law, Weidemann said, the village’s current land-use controls would remain in effect for two years after dissolution. After that, the local rules would cease to exist and would be replaced by whatever zoning and planning the successor town or towns adopt.

Like other communities of its era, the village of Greenwich is densely settled and pedestrian oriented, and it includes a historic district -- encompassing 165 structures and six parks in the center of the village – that has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1995.

The town of Greenwich, by comparison, has fewer development regulations. It’s still largely rural but in recent decades has seen a wave of commercial sprawl along Route 29 west of the village line.

Study in progress

Doonan, a Green Party member who was first elected in 2008 on a nonpartisan slate, started evaluating a variety of consulting firms after learning of the dissolution proposal in March. He narrowed the field to three and eventually chose the group led by Weidemann. The mayor said it was the least expensive proposal and came highly recommended by Schuylerville Mayor John Sherman, based on the consultants’ previous work on that village’s dissolution study.

Even if dissolution is voted down, the study will provide information on sharing services with neighboring communities, Doonan said. A grant of $45,000 awarded by the state Department of State will largely cover the cost of the study.

An 11-member dissolution study committee now includes the village mayor, Greenwich Town Board members Robert Jeffords and Eric Whitehouse, Easton Supervisor Dan Shaw, and seven other Greenwich town and village residents.

Sewer and water issues – whereby improvement districts and a joint water board may be created to oversee needs in the towns of Easton and Greenwich – and the issue of continuing fire protection also need to be addressed.

In the latter case, the town can establish a fire district, which would be governed by the Town Board or by a separately elected board of fire commissioners. The village’s current volunteer company would have to establish itself as an independent fire company in order to be eligible to contract with the town or fire district, and a facility would continue to be needed to house the existing apparatus and equipment.

Additionally, while village employees would lose their jobs, the town would have to decide whether it needs to hire or retain some of those employees to address the increased workload as it takes over services such as road maintenance in the village.

Shaw said he believes village residents within his town would realize a savings is dissolution is approved -- and that townspeople outside the village line wouldn’t see much change in their current tax burden.

“I don’t have a horse in the race,” Shaw said. “I just want people to have as much information as they can have.”

State incentive payments

Gregg is adamant that tax bills will go down if the village government is eliminated.

“There’s a huge financial incentive sitting on the table and certainly worth looking at,” he said. “Taxes for village residents will be dramatically lower and even town residents will likely see their taxes go down as well. The reason is that the state will be sending back a sizeable check every year to the towns in perpetuity.”

That state check, formally known as the Citizen’s Empowerment Tax Credit, would provide an estimated annual payment of about $270,000 to the town of Greenwich and about $30,000 to Easton.

This incentive payment for communities that go through a consolidation process, however, is subject to the annual state budget process and potentially could be withdrawn in the future – in much the same way that the city of Saratoga Springs lost revenue in 2009 when the state stopped giving the city a share of revenue it had promised from video lottery terminals at the local harness-racing track.

“To expect that lump sum forever is unrealistic,” Doonan said.

Weidemann also questioned whether the annual payments would really continue in perpetuity.

“It is annual, but there are people who are skeptical when there is state aid given for an unspecified period of time,” he said.

The village of Salem has scheduled its dissolution referendum for Aug. 5.

“I don’t think it is as controversial in Salem as it is in Greenwich, because there are a lot of different dynamics,” Salem town Supervisor Seth Pitts said. “We have two buildings and three employees, no police department, and the fire department is an entity all its own.”

Since November, the village has lost six businesses on Main Street, Pitts added.

Village officials in Greenwich are scheduled to present a draft interim report on dissolution at a public meeting on Monday, June 16. The report will also be mailed to village residents in the days leading up to the June 24 referendum.